Rising to the moment: Addressing COVID-19’s challenges by advancing data interoperability

Therasa Bell

Jessie Laurash

Improved interoperability in healthcare data exchange has been one byproduct of the COVID-19 pandemic that may ultimately help improve the delivery of care — as well as its cost eff ectiveness — in the United States.

The exchange of patient data has seen innovation at an unprecedented speed throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare organizations paused or abandoned long-term, expensive IT and interoperability initiatives in place of near-term, high-impact projects that would address the more immediate need for effective information flow among providers and systems. The most significant of these initiatives have focused on engaging patients in remote venues, including their homes, while using data to maintain personalized care delivery.

Unlike previous stimuli to data sharing in healthcare, the pandemic forced all stakeholders to collaborate efficiently on solutions. As near-term challenges created by COVID-19 threatened to disrupt the delivery of healthcare, healthcare organizations were compelled to cast aside the administrative conventions that historically impeded more effective data exchange in order to meet those challenges.

As a result of this new collaboration, providers and their IT partners have tapped opportunities for efficiently improving data sharing, even beyond COVID-19, while addressing the market’s growing demand for an interoperable data ecosystem. The solutions described here serve as a guidepost for how to solve data-sharing challenges, drive efficiency and reduce costs, while improving the provider and patient experience.

Interoperability success: Driving solutions from within

In the early stages of the pandemic, providers leveraged their existing IT capabilities to rapidly address immediate needs for improved data interoperability.

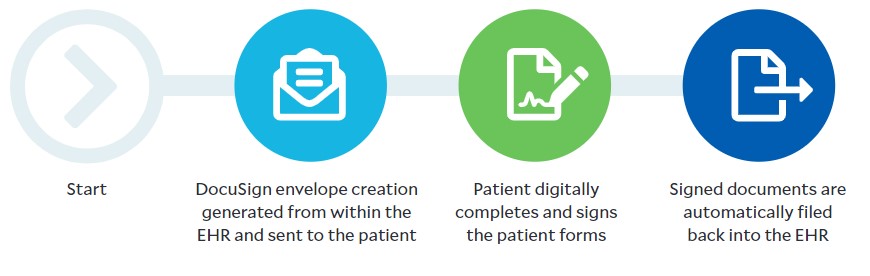

Application of electronic signing solutions. For example, as providers set up drive-through COVID-19 testing arrangements and enabled telehealth virtually overnight, they faced an immediate need for contactless patient consent. Although electronic health records (EHRs) were equipped to handle traditional consent processes, COVID-19 required creative solutions that would avoid the use of paper or shared signing tablets. Providers looked internally at the electronic signing solutions they owned, such as DocuSign®. Often, these solutions were already in use in most administrative areas of their organizations, and many patients were personally familiar with them. During the pandemic, providers broadened their use of electronic signing solutions to clinical areas as well.

To bridge the data-sharing gap, many providers took advantage of existing EHR interoperability tools, such as direct secure messaging, through the DirectTrust™ network and quickly created a “closed-loop” electronic signing transaction.a

As a result of a recent partnership with a connectivity-as-a-service provider, DocuSign’s eSignature can connect to and exchange data with any certified EHR. Patient demographic and key clinical data flows from the EHR into DocuSign, thereby transforming the generic form into a personalized experience for the patient. The signed document then flows back into the EHR.

Consent/admissions workflow

Reduced reliance on manual processes for patient record requests. Another challenge faced by providers was the reliance on manual processes, acutely illustrated in the shift to remote work for nonclinical staff. Many such processes would involve sharing critical patient information between providers and public health organizations through manual retrieval of records and fax machines.

Traditionally, for instance, fax-machine-dependent workflows were used to meet the need of non-affiliated providers in a community to be able to access disparate patient records, but with no onsite staff to manage the requests, new methods were required. Opening health system portal access to select community providers was a potential solution, but it was often ruled out due to the requisite training and onboarding of providers by IT staff who were already overwhelmed with daily COVID-19 operations.

As with patient consent workflows, however, it was determined that the interoperability tools provided by the EHR could be used to address patient record requests. Prior to the pandemic, most major EHR vendors were participating in on-demand and secured access to clinical information within their EHRs via trust communities, including Carequality and the Commonwell Health Alliance®, for treatment purposes. Given the extent of the participating population, providers using these EHRs were already capable of electronically accessing and providing the records of shared patients that traveled between them.

Over the course of the pandemic, Carequality saw a 59% increase in provider participation, and Commonwell Health Alliance realized a 244% increase in clinical document exchange between providers. However, community providers using non-participating EHRs, such as those in post-acute or behavioral settings, were limited. To respond to this gap in care delivery, Carequality implemented a waiver that allowed providers to query for patient records on demand without the requirement for reciprocity from their EHR during the declared public health emergency (PHE).

Sharing of testing information. Electronic sharing of basic testing information with public health and other providers for tracking purposes did not exist prior to the pandemic. As COVID-19 swept the country, public health agencies were overwhelmed with increased fax volume involving requests for such information. New electronic solutions were quickly put in place, including the use of EHR direct messaging capabilities to push COVID-19 information to the agencies. Throughout the early stages of the pandemic, more than 40 million direct messages were sent containing electronic case reports for COVID-19 diagnoses, according to DirectTrust. In the face of waning COVID-19 cases, direct messaging capabilities continue to be used to replace historical fax workflows.

3 use cases in improved data interoperability, and actions for CFOs

By leveraging and expanding the use of existing IT tools and exploring readily accessible interoperability capabilities, providers can elevate care coordination among all network participants. Here, we highlight three use cases applying this framework that can drive immediate impact to care delivery and cost reduction.

1 Transitions of care/referrals

Meaningful use of financial incentives drove the initial application of direct secure messaging for the basic referrals. The pandemic enhanced its usage. As of today, there are 2.7 million direct addresses in DirectTrust’s provider community, the company has reported, making it a useful and effective tool for provider organizations looking to digitize and automate many fax and phone-based workflows.b

Action: Hospital and health system CFOs should assess the extent to which their organizations have an opportunity to digitize and streamline manual processes involved with patient referrals and transitions into and out of the hospital.

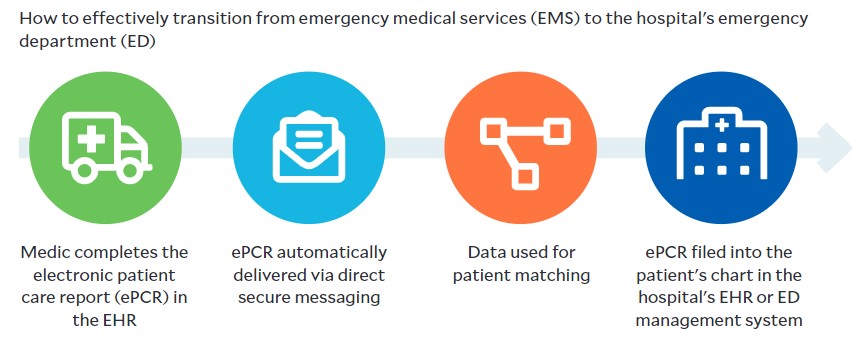

Application example: There is a significant opportunity to transform the patient information hand-off process from an emergency medical services (EMS) team to emergency department (ED) staff awaiting the patient’s arrival. While transporting the patient, the EMS team can use their EHR to create an electronic patient care report (ePCR). The ePCR provides documentation of the most critical aspects of the patient’s care, including the medications administered and procedures performed en route to the hospital.

The hand-off of the ePCR to the ED team is often delayed because many health systems use a manual, fax-driven process for this action. As a result, the EMS and ED teams often are forced to rely on verbal communication to convey this important information regarding the transition of the patient and their clinical status. Direct secure messaging could be used to transmit the information contained in the ePCR from the EHR of the EMS agency to the EHR of the hospital.

Automated EMS workflow

2 Orders and plans of care approval

A five-page care plan results in 20 fax pages. A physical therapist (PT) sends a five-page (five pages sent) care plan via fax to the referring provider for signature (five pages received). The referring provider signs and sends back to the PT (five pages sent, five pages received). There is significant opportunity to reduce this inefficiency and its associated cost using digital processes.

Action: Hospital and health system CFOs should evaluate workflows and signing opportunities to move away from fax transactions and toward electronic signature workflows. This move should include engaging the organization’s community providers and EHR vendors to transition to electronic forms of exchange.

Application example: Beyond the emergency measures around patient signature workflows that were implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, health systems should consider expanding the use of electronic signing solutions to address provider-signing workflows, including care plans and orders.

3 Record requests/release of information

Although the release-of-information process in health systems is becoming more automated, many organizations continued to manage the process workflows manually. Moreover, delays in this process, when performed manually, can have a profound impact on the exchange of clinical information and thus patient care — and conceivably the greatest impact of all, manual processes that could benefit from improved interoperability.

Health systems also devote significant annual costs to either dedicated staff or outsourced services contracts to manage the inbound fax or voice-based record requests from provider and non-provider entities. The growing provider participation in Carequality — surpassing 600,000 physicians, 50,000 clinics and 4,200 hospitals — provides strong evidence that treatment-based record requests from external providers are prime for transition from fax-based workflows to electronic, on-demand requests.c

Action: Hospital and health system CFOs should encourage their organization’s participation in interoperability networks or implementation of digital tools with providers and other entities with which their organizations frequently exchange data.

Application example: Portals supporting record requests via Carequality serve as efficient tools to allow providers themselves to respond quickly to requests and avoid the delays that occur when processed through the heath information management department.

Continuing the momentum

As the pandemic continues to ebb and flow, prioritizing and innovating the electronic exchange of patient information should continue unabated. The pandemic shone light upon the inefficiencies across administrative and clinical workflows that ultimately impact the quality of care.

The ability of hospitals and health systems to rapidly deploy digital solutions to address the acute interruption of human operations underscores the reality that interoperability in healthcare is neither elusive nor requires significant investment in new and extensive IT infrastructure. By leveraging current capabilities, augmented by readily accessible tools, providers can meet the growing demands related to more extensive data sharing and, in so doing, improve the accessibility and delivery of care.

Footnotes

a. DirectTrust is a member organization focused on promoting secure exchange of health information.

b. DirectTrust, “DirectTrust reports upsurge in direct exchange transactions during the second quarter,” News release, Aug. 4, 2021.

c. Carequality, “Carequality interoperability framework adopters,” Page accessed Oct. 8, 2021.

How we got here: Foundational steps for interoperability in healthcare

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the healthcare industry was primed for a move to greater data interoperability. The evolution, adoption and Federal endorsement of Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standards created a common framework for healthcare, creating an application programming interface (API) and data sharing. Further, the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) and CMS mandated the prevention and elimination of anti-competitive data blocking practices and increased data sharing capabilities for CMS-regulated payers through the 21st Century Cures Act, with many of the regulations going into effect over the past 18 months.

This enabling regulation stemmed from two trends:

- An exponential increase in patient data and growth in connected devices caused healthcare data to rapidly proliferate.

- The migration of care to new settings (e.g., outpatient, home-based) resulted in an increased diversity of data sources, requiring a new paradigm of management and oversight.

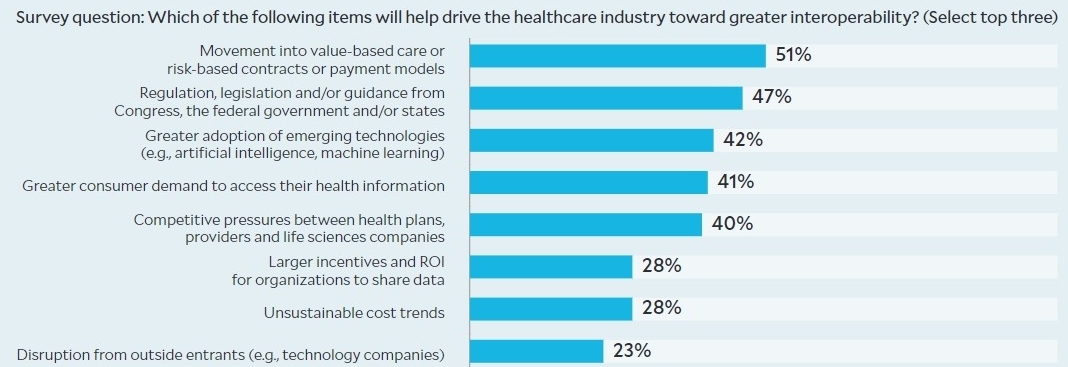

Hospital executives surveyed by Deloitte also indicated that greater interoperability in healthcare was needed first and foremost to support the shift to value-based care; organizations would need to leverage and share large amounts of data to build proper value-based/risk-bearing care models that are financially viable and capable of reducing costs across the healthcare system.

These various market tailwinds converged because the industry recognized the need for, and importance of, healthcare data interoperability; the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that it is imminently achievable. Recent examples from across the ecosystem, described in the main article, support this assertion.

Key drivers of interoperability in healthcare

Please note: Multiple selection of responses allowed. Total; response = 100. Source: Deloitte 2019 Healthcare interoperability survey, exhibit appearing in Biel, D., DeLone, M., Gerhardt, W., and Chang, C., Radical interoperability: Picking up speed to become a reality for the future of health, Deloitte Insights, Oct. 24, 2019.

Copyright © 2021 Deloitte Development