Hospitals work to make the supply chain green

At a time when sustainability increasingly is a strategic priority in the healthcare industry, the supply chain represents a formidable challenge and an enticing opportunity.

Even with all the challenges facing hospitals and health systems these days, the push to make operations more environmentally sustainable is becoming viewed less as a differentiator and more as an essential strategy.

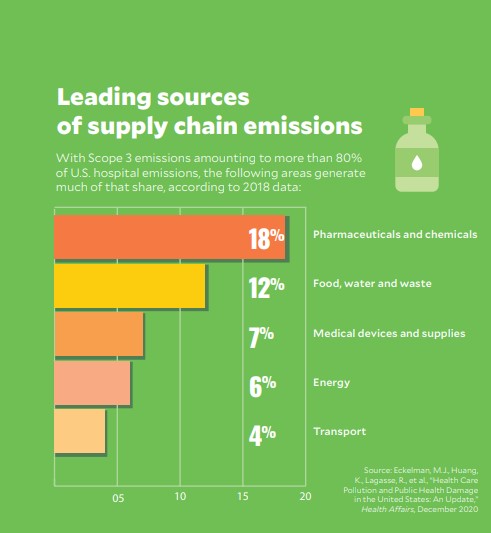

And for those organizations that have mastered energy conservation methods and made progress in greening their facilities and physical infrastructure, the supply chain looms as the next big target. Globally, the supply chain represents more than 70% of the carbon emissions produced by the healthcare sector, according to an estimate in a 2019 paper by Health Care Without Harm.a

Finding innovative and comprehensive solutions is daunting given the vast network of manufacturers, distributors and products that constitute the notoriously opaque supply chain. Recognizing the stakes, however, more organizations are determined to try.

“It’s now a huge conversation,” said Jon Utech, senior director of Cleveland Clinic’s Office for a Healthy Environment.

smaller hospitals can join together in efforts to improve supply chain sustainability.

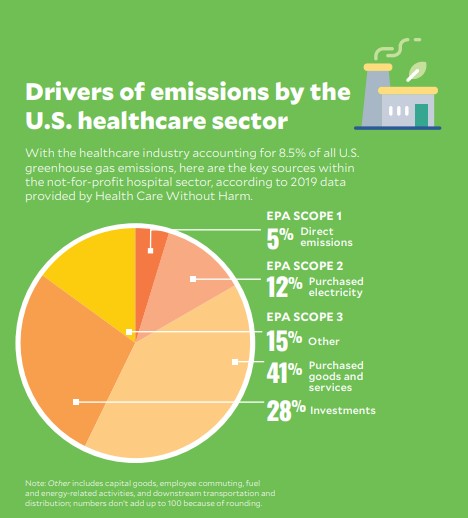

The quest for a green supply chain and sustainability in hospital operations more broadly is based on several pressing concerns, including incentives from the investment community related to environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors (see related article). Also, with the healthcare sector contributing an estimated 8.5% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, per federal data, hospitals increasingly see improved environmental practices as central to their mission to support the health of their communities.

“The outside world is looking in at healthcare and saying, ‘Boy, for folks who want to keep people healthy, you guys aren’t doing as good a job as we’d like [with emissions],’” said Aaron Bernstein, MD, MPH, a practicing pediatrician and the interim director of Harvard’s Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment.

Much of the room for improvement, he added, is in the supply chain and waste reduction.

Striving for better visibility

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) categorizes supply chain emissions as Scope 3, meaning those that are attributed to an organization due to its association with manufacturers, distributors or other entities that produce the emissions. (Scope 1 emissions are directly generated by an organization on-site, and Scope 2 refers to emissions stemming from an organization’s use of purchased energy such as electricity.)

Assessing Scope 3 emissions long has been difficult. Health systems and group purchasing organizations (GPOs) over the past several years have made progress in persuading manufacturers to disclose data on a range of issues such as potentially harmful chemicals that appear in packaging.

“You pretty much couldn’t get this data five years ago,” Utech said. “There’s a lot of data now.”

The change has come as stakeholders use leverage that, by and large, they didn’t think about using until recently.

“Purchasers have so much power, especially healthcare purchasers with the amount and volume of materials that they procure,” said John Ullman, director of safer chemicals and procurement for Health Care Without Harm.

“[Transparency] really can flow through the supply chain,” he added. “The purchasers can request the GPOs to request the suppliers to request their subcontractors and tier-two, tier-three suppliers — transparency is important in all of those stages.”

Acting on the data

The increased transparency has allowed Cleveland Clinic to start setting goals for managing the environmental impact of products, Utech said. Those targets include ensuring a certain percentage of products are purchased locally to reduce emissions or are defined as environmentally preferable by groups such as Health Care Without Harm and the Healthcare Anchor Network, with criteria including use of safer chemicals and reusable materials.

waste reduction, such as ensuring

supply packaging is reusable.

Intermountain Healthcare, the Salt Lake City-based system that operates 33 hospitals, likewise aims to promote sustainable procurement, said Glen Garrick, system sustainability manager. At the most basic level, that goal encompasses efforts to reduce hazardous chemicals in the health system’s products, services and facility operations.

“They’ve been deemed hazardous, but they’re not regulated at all,” Garrick said. “That’s one of the challenges — the EPA isn’t coming out and saying, ‘Hey, this is a bad chemical. Don’t use it.’ We’re not waiting for someone to tell us not to use it.”

Another area of focus is waste reduction, such as by ensuring supply packaging is reusable. Garrick recently learned of a vendor that modified the packaging of one product to include 90% recycled material.

“This is what we’re looking to all of our vendors for, to be taking these steps,” he said.

GPO executives at Charlotte, North Carolina-based Premier hope to lead an effort to cut back on the use of disposable products and move toward reusables when doing so is clinically feasible, said Andrew Knox, manager for environmentally preferred products.

Premier’s hospital members are also looking at anesthetics, a greenhouse gas that makes up a “meaningful portion of most healthcare systems’ Scope 1 emissions,” Knox said.

“It just so happens that the most environmentally damaging anesthetic [desflurane] is also the most expensive,” Knox said, meaning hospitals can realize cost savings from a move that also benefits the environment.

“There are alternatives out there that are, in most cases, clinically equivalent,” he added.

Building on industrywide momentum

For smaller hospitals that lack influence with suppliers and perhaps aren’t part of a forward-looking GPO, there is power in numbers, Harvard’s Bernstein said.

Such organizations can unite to share products and supplies in the same manner as hospitals within a large system, Bernstein added, creating closed-loop use of anything from printer toner to surgical equipment.

For hospitals with fewer resources, small steps can make a difference. Even making sure IT purchases are Energy Star certified would be worthwhile, Knox noted.

“Those numbers are sometimes hard to capture because they get lost in the electricity bill, but they are real and they are meaningful,” he said.

When crafting a sustainability strategy, a viable early step is a “basic waste audit,” Bernstein said, which allows organizations to pinpoint segments of their supply chain with the most room for improvement.

“Health systems tend to be pretty Balkanized,” he said. “We tend to have cost centers that work independently, so we don’t get a bird’s-eye view of where resources are being wasted at an institutional scale.”

That issue points to the importance of having a C-level sustainability officer with the authority to set and implement strategies, he added.

Utech, who fills that role at Cleveland Clinic, has nudged his organization to go beyond examining the sustainability of individual products. Gauging the environmental principles of supply chain partners has become standard procedure.

About three years ago, Utech said, Cleveland Clinic began having conversations like: “What are your climate goals? What’s your commitment to recycling?” Such questions have become part of the RFPs the organization puts out, and a requirement to disclose sustainability data is included in contracts.

Previously, annual purchasing reviews were “much more product-focused and, at the corporate level, credit-focused,” Utech said.

Of course, financial considerations can’t be overlooked as hospitals and health systems endure tightening margins amid an array of financial and operational challenges, including staff shortages and related labor costs. But organizations often won’t have to choose between supply chain sustainability and cost efficiency.

“We’re certainly seeing examples where companies are improving the environmental performance of their products while keeping costs flat — but in some cases actually reducing them by really looking at the product right from its fundamental function and redesigning it in ways that are both more environmentally friendly and more cost-effective,” Knox said.

Staying agile

Garrick joined Intermountain Healthcare near the pandemic’s start, just as inventory levels became an overriding concern.

“The need for supplies often trumps different decisions around sustainability,” he said. “But I can tell you in my more recent meetings, there’s no mention about not having enough supplies. The discussions now are around making decisions that are more sustainable for the environment and for our services.”

The pandemic also represented a step backward for efforts to reduce reliance on disposable products and single-use devices. Safety protocols called for tossing many products after one use to lower infection.

Intermountain is trying to regain the progress it had made in incorporating reusable devices, especially as part of an initiative to “green the OR,” Garrick said.

“But each one of those transitions is pretty difficult,” he said.

The conflict illustrates that “sustainability professionals need to work closely with their infection control professionals to try to find that win-win situation,” Knox said, noting that not all disposables improve patient safety.

Such considerations exemplify the challenges in creating a green supply chain, but also the determination of stakeholders to find solutions.

“We’re definitely seeing more and more interest from our members in this area,” Knox said. “There’s a fundamental motivation.”

Footnote

a. Health Care Without Harm and Arup, Health care’s climate footprint: How the health sector contributes to the global climate crisis and opportunities for action, Climate-smart healthcare series, September 2019.

A public commitment

Hospitals and other healthcare organizations can sign on to the Health Sector Climate Pledge, a Biden administration initiative in which participants commit to:

- Reduce organizational emissions by 50% by 2030 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, relative to a baseline no earlier than 2008

- Publicly report on progress every year

- Conduct an inventory of supply chain emissions by the end of 2024

Systems representing 837 hospitals had signed the pledge as of Nov. 10.

Update: The pledge is closed but may reopen in the future. The resources on the signup page at the link above remain available as tools for organizations seeking to improve their sustainability efforts.