Maryland TCOC: A grand demonstration continues

The Maryland Total Cost of Care (TCOC) program, one of the nation’s most innovative advanced alternative payment (APM) models, has entered year two. Finance leaders across the nation can benefit from a closer look at how this state-level program works and its implications for the future direction of healthcare financing nationwide.

Under the TCOC program, for the first time, a state under a global budget is accountable for the total cost of care of all Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. The program warrants finance leaders’ attention because the innovative way it addresses the challenge of reining in the rising costs of nation’s healthcare system: All Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries must be attributed to primary care physicians and/or a hospital —whether or not the beneficiary has received services that year. Competing hospitals and systems form geographically based networks to ensure regional and statewide coverage. The Medicare performance adjustment (MPA) tracks each hospital’s total cost of care with a 1% upside or downside incentive. To the extent the program is successful, it could provide a basis for future Medicare reform nationwide.

With its second year, the program has seen its first round of annual update factors and annual performance adjustments. Here we provide a review of the essential elements of this major financing and policy initiative, which is a transformation from Maryland’s earlier hospital All-Payer Model (see the sidebar below for details on the evolution of the TCOC Program).

Essential TCOC elements

The following entities play fundamental roles within the TCOC program.

Hospitals. Under Maryland state law, hospitals are the regulated and enforceable entities. Under TCOC, hospitals face cutting-edge regulatory complexities and simultaneously provide major care advances.

The Health Services Cost Review Commission (HSCRC). The HSCRC, Maryland’s rate-setting commission established in 1971, is a national leader in guiding innovative hospital performance payment principles and policies. HSCRC staff extend these principles and policies to the TCOC implementation and evaluation with substantive advice from multiple stakeholder workgroups.

Chesapeake Regional Information System for Patients (CRISP). CRISP is an advanced statewide health information exchange (HIE) established in 2006 (see crisphealth.org). This HIE is the essential repository for hospitals’ and most physicians’ encounter data both for pathways of care and TCOC program monitoring. CRISP supports both a statewide image exchange and links to the major electronic health records (EHRs). The HIE processes more than 100,000 queries per week in its secure portal and one million pieces of data delivered in to EHRs per week.

Clinicians. Physicians, often less attentive to rate setting, are front and center in TCOC. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) contract requires that each fee-for-service Maryland Medicare beneficiary be attributed to a primary care physician who is linked to a hospital. The clinician-hospital dyad is responsible for the beneficiary’s total cost of care. Maryland’s Department of Health also is developing the Maryland Primary Care Program to provide these physicians with additional support.

Other key factors

Two key factors in the TCOC program are the process for the Medicare MPA, including beneficiary attribution, and the program’s fundamental focus on quality.

MPA and beneficiary attribution. The attribution process establishes hospitals’ risk populations by identifying hospital-specific populations that answer the question, “Which beneficiaries belong to which hospitals?” This hospital-specific population provides the basis for hospitals’ and clinicians’ efforts to manage the state’s TCOC. The CMMI contract requires an algorithm for attributing Medicare FFS beneficiaries to Maryland’s hospitals in order to calculate and monitor the MPA. The MPA is a 1.00% upside/downside incentive depending on the hospital’s per-member-per-month (PMPM) performance. Performance is calculated by the hospital’s attributed beneficiaries’ PMPM performance in comparison with Maryland state and CMMI national data. The quality measures and their weight within MPA have yet to be defined.

Focus on quality. Although Maryland is exempt under its Medicare waiver from CMS’ prospective payment system, quality performance is required by the state’s contract with CMMI and is tracked with measures comparable to CMS requirements. Hospitals’ budgets are affected by the quality of their performance. New for 2020 are care transformation initiatives (CTIs) for a hospital or network of hospitals to target a reduction in total care costs for a defined population. There are upside and downside risks.

The global revenue and annual update factors

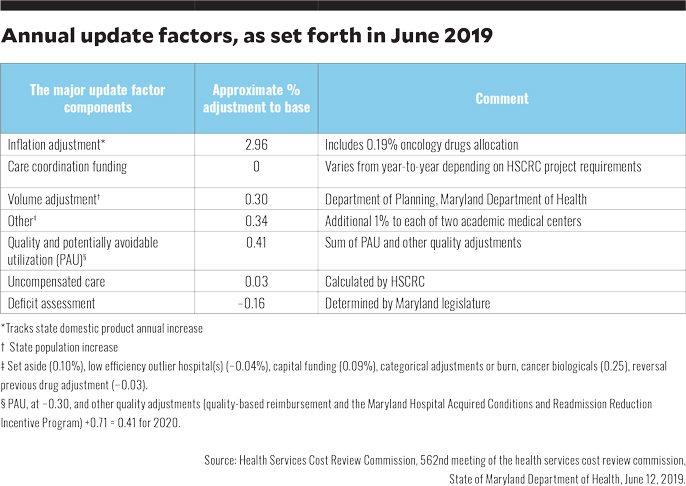

The TCOC global revenue is straightforward in concept but complex in implementation. A hospital operates from its base-year budget. This budget is annually incremented upward by the HSCRC-determined update factors (see the chart below). The hospital’s performance year revenue is further enhanced or debited based on performance with respect to quality and utilization performance.

The hospital’s year-two performance revenue incorporates the prior year’s net quality savings and annual update factor. Most performance measures include all payers. The MPA requires in-depth understanding of Medicare beneficiary care. Attribution of beneficiaries drives MPA performance.

The annual update includes a price and volume adjustment that is applied on a hospital-specific basis. The annual volume adjustment is a fixed amount based on age-weighted population growth in the hospital’s service area. For the Rate Year 2020, the update was 3.56% for revenue and 3.25% per capita.a

A work in progress

In Maryland, the transition from a hospital-based all-payer model to the TCOC model is proceeding, even as questions abound regarding the overall impact of innovative payment models.b Maryland is unique, and the stakes are high. Election cycles elevate attention to healthcare access, quality and cost. Although “Maryland for All” is not an option, the intersection of data-driven global budgets, beneficiary attribution and aligning risk-based, population incentives are fundamental to improving access, quality and reducing total cost of care.

About Maryland’s TCOC program

Maryland’s Total Cost of Care (TCOC) program is the result of the 40-year waiver of Medicare rules that requires all payers, including Medicare, Medicaid and commercial insurance companies, to pay the same rate for the same hospital service at the same hospital. The TCOC program, which commenced operations Jan. 1, 2019, emerged from negotiations between Maryland and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) aimed at amending the state’s previous All-Payer Model, which was established under the waiver in 2014. The objective was to create a new model that would align hospital and physician incentives and qualify as an advanced alternative payment model (APM) under CMS’s Quality Payment Program (QPP) established under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA).

The program’s eight-year contract uses financial targets, outcomes-based credits, care redesign and a quality program sufficient to meet provider requirements for an advanced APM.c It is intended to build on the successes of the previous All-Payer Model, which encompassed hospital inpatient and outpatient services and, according to CMMI, resulted in a 2013 to 2018 cumulative savings of $869 million.d While initial evaluations were not decisive regarding the amount and source of savings, recent evaluations documented those savings from both inpatient and outpatient sources.e

Footnotes

a. Health Services Cost Review Commission, 562nd meeting of the health services cost review commission, State of Maryland department of Health, June 12, 2019.

b. Chernew, M.E., “Do commercial ACOs save money? Interpreting diverse evidence,” Medical Care, November 2019; and Roberts, E.T., McWilliams, J.M., Hatfield, et al., “Changes in health care use associated with the introduction of hospital global budgets in Maryland,” JAMA Internal Medicine, February 2018.

c. Sapra, K.J., Wunderlich, K., Haft, H., “Maryland total cost of care model: transforming health and health care,” JAMA Network, February 21, 2019.

d. Health Services Cost Review Commission, Maryland’s All-Payer Model Results, 2019.

e.Daly, R., “Maryland’s global budget model: Impact on overall healthcare utilization remains murky,” HFMA News, April 11, 2019; Beil, H., Haber, S.G., Giuriceo, K., et al., “Maryland’s global hospital budgets: Impacts on Medicare cost and utilization for the first 3 years,” Medical Care, June 2019; and Done, N., Herring, B., Xu, T., “The effects of global budget payments on hospital utilization in rural Maryland,” Health Services Research, June 2019.

What to know

Essential characteristics of a statewide global budget for total cost of care:

- Beneficiaries are attributed to a regulated provider, which in Maryland are hospitals

- Hospitals and clinicians are responsible for providing care for all Maryland beneficiaries within the hospitals’ global revenue which is based on the annual state all-payer revenue update

- Total-cost-of-care incentives align hospitals, physicians and post-acute care providers