HEALTHCARE 2030: Value-Based Care?

Still waiting for value-based care

By Lola Butcher

HFMA Contributing Writer

The effort to adopt value-based payment in healthcare is losing some of America’s biggest healthcare purchasers: large employers, many of which are giving up on the concept.

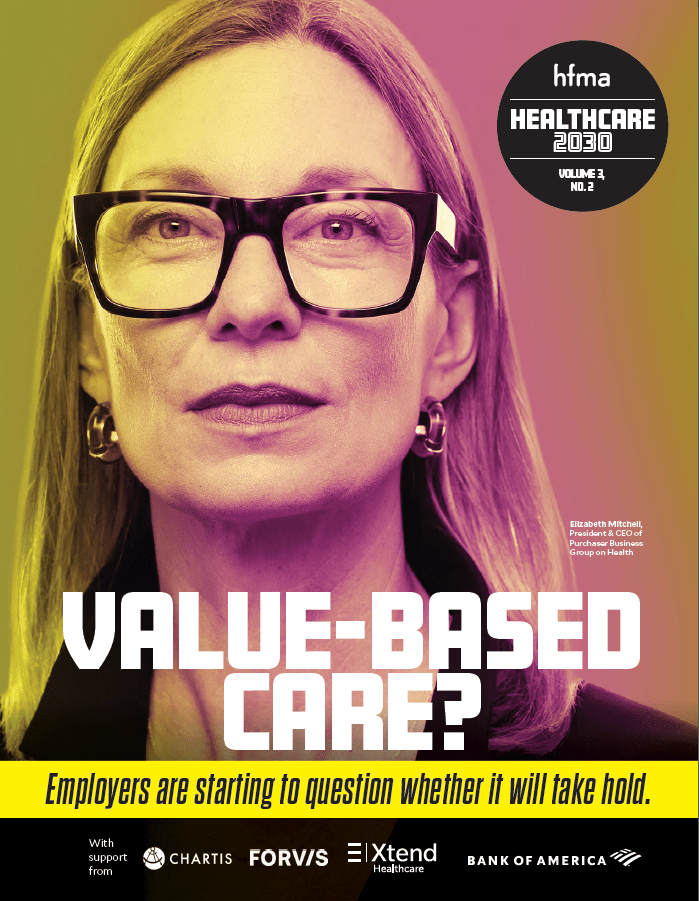

“It has been a failure to date because obviously we do not have value in healthcare,” said Elizabeth Mitchell, president and CEO of Purchaser Business Group on Health (PBGH), which is shifting a big part of its focus on other cost-saving strategies.

The group’s members are nearly 40 huge employers and public purchasers — Microsoft, Walmart, Boeing are a few of them — that collectively spend $350 billion on healthcare annually. They, among others, have lost confidence that the so-called value movement in healthcare is the salvation it was supposed to be. Without employers’ insistence, it’s unclear if value-based care will ever take hold.

“Prices have gone up dramatically and quality has not,” Mitchell said. “So value has decreased, and I do not see any serious attempts to change that by most of the industry players.”

Economists Michael Porter, PhD, MBA, and Elizabeth Teisberg, PhD, coined the term value-based healthcare to envision a system in which physicians and hospitals are rewarded for value — the best quality of care at the lowest cost — instead of volume, where they rack up revenues with fee-for-service (FFS) payments.

Many important stakeholders — CMS, health systems and commercial insurers — saluted the vision of value-based care. In the past 15 years, hundreds of experiments to replace FFS contracts with alternative payment models (APMs) have launched. Many of them have reduced costs and improved quality — and many have not.

NOT GIVING UP

APMs still have a sizable number of supporters. Management at Allina Health, a two-hospital system serving Minnesota and western Wisconsin, was disappointed with its early value-based arrangements, but its board of directors recommitted to value-based care in 2019.

— Ric Magnuson, CFO, Allina Health

“We are doing it because we believe it’s the right thing to do for our community,” said Ric Magnuson, MBA, the system’s CFO.

And in the long run it’s also the right thing to do for health systems because CMS, the nation’s biggest payer, is doubling down on value-based care.

“We’re definitely in a better place, especially because I don’t think the status quo is going to be an option,” Magnuson said. “And if you’re not on this journey to value-based care, there’s going to be a wake-up call someday.”

Years ago, OSF HealthCare, based in Peoria, Illinois, reached the point where it could attribute about 26% of its patients to value-based contracts. But since then, it has been stuck at that level.

“We have interest in it, and we have had some success, particularly in our shared-risk and capitation agreements,” said Michael Allen, FHFMA, MBA, CFO of the 15-hospital health system. “But we have not seen an appetite from the payer side to do more.”

COSTS KEEP CLIMBING

Skeptics point out that, despite all the attention to value in the past two decades, healthcare costs overall have continued to rise almost every year. CMS actuarial estimates show that national health spending grew by an average of 4.8% annually from 2011 to 2021, arriving at a total of $4.3 trillion in 2021, which is 18.3% of gross domestic product.

“We have lost the plot when we talk about value-based care,” Mitchell said. “It’s lots of complicated contract elements, but we forget that we are actually trying to achieve lower total cost of care and better health outcomes. The payment method is just in service to those goals, and I feel like people forget that.”

— Andréa E. Caballero, interim co-executive director of Catalyst for Payment Reform

The nonprofit Catalyst for Payment Reform (CPR) — whose members include private employers, public purchasers, state health insurance exchanges and others — was founded in 2009 to push for value-based payments. In 2010, CPR estimated that just 1%-3% of healthcare dollars were tied to quality; in 2022, its estimate surpassed 60%.

Andréa E. Caballero, MPA, CPR’s interim co-executive director, finds little satisfaction in that progress. APMs were designed to increase affordability and improve quality by reducing waste and improving care coordination, and they have been only incrementally successful.

“You probably could find evidence of improved care coordination here and there and on reducing waste kind of on the edges,” she said. “But as for affordability, APMs do not address high unit prices, and year after year, all of the evidence shows that it’s prices, not utilization, that’s driving up commercial costs.”

CONTINUED BELOW

OSF plans for value-based care in Medicaid

Clinging to fee-for service

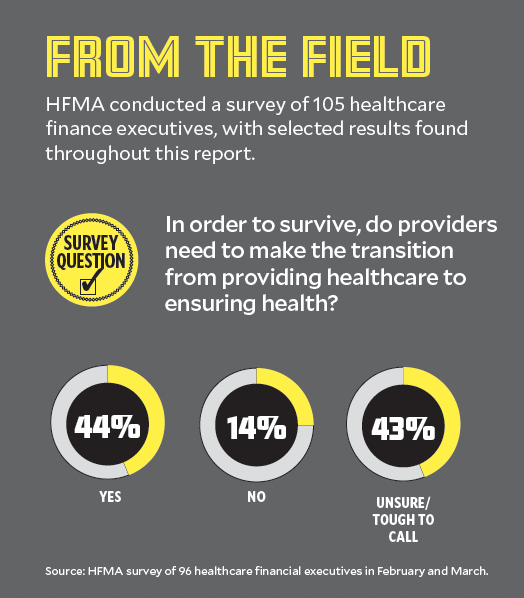

In a survey conducted by HFMA for this report, 43% of respondents said they were unsure or found it too tough a call whether or not providers should transition to focusing on health from a focus on providing healthcare in order to survive. Another 14% said such a shift was not needed.

David Johnson, HFMA board member and CEO, 4sightHealth

David Johnson, HFMA board member and founder and CEO of 4sight Health, said the pivot away from FFS to value-based care contracts stalled out because many so-called value-based arrangements are based on FFS rates.

“Despite all this talk about value the last 10 years, we still have 80%-85% [of payments] in fee-for-service,” he said. “Health systems continue to cling to the payment model.”

There is an incentive to do so when per-unit prices are high. In Johnson’s view, the majority of healthcare services are routine, meaning the health system knows just what to do when the patient presents for care. In other industries, that situation typically triggers price reductions as a way to compete, he said.

“Basically, what we’re saying as an industry is it’s OK to charge premium prices for routine services because we’re healthcare,” he said. “And I just don’t think the wider marketplace accepts that anymore.”

Sachin H. Jain, CEO of SCAN Health Plan said the culture of being a CFO in healthcare needs to change.

Sachin H. Jain, MD, MBA, CEO of SCAN Group and SCAN Health Plan, has also soured on valued-based care as a panacea to America’s healthcare cost crisis. Provider organizations still measure their success by growth, which means increasing revenues.

“We need to change the culture of being a CFO in American healthcare,” said Jain. “Maybe in a world where everyone is healthier, healthcare organizations don’t grow — they shrink. The next generation of CFOs needs to challenge themselves on a new set of metrics above and beyond top-line and bottom-line revenue as a measure of performance.”

So what’s the answer?

PBGH’s goal: Zero growth in healthcare costs.

“At least two of our members have achieved a flat trend with better outcomes, so we know it’s possible,” Mitchell said.

In her view, reducing specialty care spending by prioritizing advanced primary care that incorporates behavioral health is the success strategy over specialty care. But PBGH members don’t believe that traditional health systems and health plans will deliver it. Their evidence: PBGH’s Health Value Index, which tracks health plan performance against PBGH priorities, shows a disconnect between what purchasers want to buy and what’s available in the market.

“We’re going into our third year; our members are saying it’s very important to them that a higher percentage of spend goes into advanced primary care, and the trends are actually going in the other direction,” Mitchell said.

Johnson of 4sight Health agrees that care delivery, not just payment method, needs to change.

“The industry needs major restructuring,” he said. “Part of what needs to happen is a shift of resources out of acute and specialty care into health promotion, primary care, chronic disease management and behavioral health.”

Tips for negotiating value-based contracts

BY LOLA BUTCHER

HFMA Contributing Writer

OSF HealthCare participates in CMS’ Medicare Shared Savings Program and in capitation, shared risk, shared savings and pay-for-performance contracts with commercial payers, so CFO Mike Allen’s years of experience negotiating value-based contracts have yielded some valuable lessons.

For example, a payer’s ability to provide meaningful data about patients, claims, trends and benchmarks is essential to success in value-based contracts. OSF HealthCare has exited some contracts because the payer could not provide data.

“If the agreements were not designed in a way that would allow us to understand how to improve the cost of care for a particular group of patients, then we unwind ourselves from those agreements,” Allen said.

Besides the mandate for payers to provide data, here are some additional tips worth considering from Allen and the CFO of Atrius Health, Patrick Holland, who also has extensive experience in value-based models.

- Ask for financial support to get started. When provider organizations are new to value-basedcontracts, payers may be willing to provide support. “Try to negotiate some management fee dollars that will help you start building the centralized programs that you will need to be successful in the long run,” said Holland.

- Keep quality metrics separate from financial risk, if possible. Value-based contracts typically include quality measures, but Atrius tries to avoid tying financial risk to quality goals. “We like to think of quality and cost as separate but related parts of the model,” Holland said. “So we try hard to negotiate upside-only for quality. But if quality is a gate to financial risk, then we work closely with our quality and safety department as well as the health plan to make sure the measures are reasonable, and we can be very confident we can meet them.”

- Be smart about the risk you take. Only accept risk for the medical expenses that you have control over, Holland said. For a primary care-only group, that may mean accepting risk only for professional services. If you don’t want to manage pharmacy costs, negotiate that in the contract.

- Don’t allow black box calculations from the payer. Transparency in payments is essential because health systems must understand how their new care models lower the cost of care. “If I just get this number that said, ‘you got this much shared savings,’ if we can’t figure out what we did to get there, it doesn’t help us,” Allen said. Likewise, the payer must be able to explain how its members are attributed to the contract in a way that makes sense. Health systems should not be held responsible for misattributed patients. “Are we getting attributed patients that maybe touch our health system, but we really don’t have enough interaction with them to help manage their care?” Allen said.

Going direct

Direct employer-to-provider contracts for elective surgeries have been a winning strategy for PBGH members, and the organization is building on that concept. It is working to build a national primary care center of excellence network, with specialty referrals based on quality.

That network may not include traditional health systems. When PBGH issued a request-for-information from organizations interested in providing advanced primary care to its members, Mitchell was surprised by the strong response.

Employers and clinicians have the same aims and employers going direct enables new and aligned relationships. The intermediaries haven’t served employers’ needs, Mitchell said.

CPR, meanwhile, is pivoting its energy from payment reform to regulation.

“Our shared agenda for 2023 is to push hard by playing the policy card,” Caballero said. “The marketplace interventions that we and others have been working on for a decade have made incremental changes in the system, but we have some significant issues that we think only state policy intervention will be able to help with.”

Knowing that not all states will be amenable to the same policies, CPR has developed five menus of policy options ranging from penalties for engaging in anticompetitive behavior to price regulation. It intends to start by focusing efforts in three states to identify what policy interventions might work best in each of those states and to push for adoption of those policies.

“We are seeing evidence that this can be a winning strategy,” she said. “Purchasers in states like Indiana, Montana, Colorado and a variety of others are definitely coalescing around the idea that outside forces need to be deployed to help address the issue of high commercial prices.”

CPR still believes that value-oriented payments are essential to lowering America’s health cost crisis.

“They are very much an element to address affordability, but it’s not the only ingredient,” Caballero said. “But addressing high prices that undermine the potential of alternative payment models is also an ingredient.”

100 years of change in one decade

Johnson thinks forces from the marketplace will change healthcare delivery more in the next decade than it has in the last century, and the industry may be reshaped along the way.

“There’s no doubt it will be a messy decade,” he said. “We’ve been making incremental changes and don’t have a lot to show for it. This increases the likelihood that it will be more of a catastrophic-level change like Medicare bankruptcy or a collapse of the provider system.”