Jeff Goldsmith: A healthcare system (and society) out of balance and how to fix the problem

There is a critical need today for meaningful, concerted action to reduce the untenably high costs of our nation’s healthcare system and redirect its misguided focus.

After nearly 15 years of cost stability, where U.S. health spending remained at or near 17.5% of GDP, the COVID-19 pandemic profoundly disrupted our healthcare system and our politics and gave rise to a sharp and ongoing increase in health spending. The prospect of fresh increases in their health benefit costs has frightened employers. Some of these costs will inevitably be passed on to workers in the form of higher cost sharing. The new federal budget will exacerbate this problem via sharp increases in uninsured patients and a reduction in unit payment for those who remain publicly insured.

But, as the cover story in the December 2025-January 2026 of hfm underlines, the U.S. healthcare system itself is not functioning effectively to meet society’s needs. How we respond both to the fresh cost pressures and the healthcare system’s urgent need to improve the societal return on its investment in healthcare will determine the future of our business.

A healthcare system out of balance

Why our nation’s health costs are so high relative to other countries has been a persistent source of concern for policymakers for decades. The U.S. health policy community has been obsessed with what it believes are flawed economic incentives in our payment system and has tied itself in knots trying to fix what might never have been the core problem.

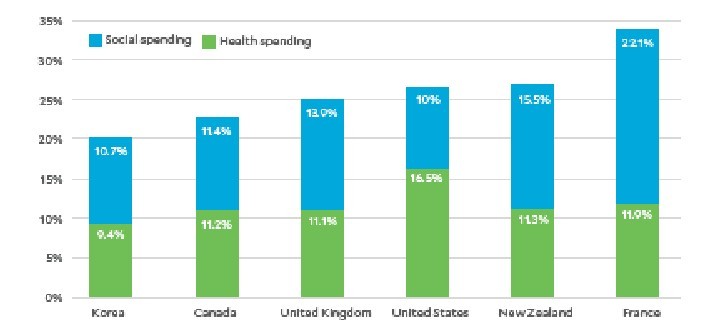

The actual core of the problem is a profound and tragic misallocation of societal resources that perpetuates unnecessarily high spending on healthcare. In their 2016 book, The American healthcare paradox: Why spending more is getting us less, Elizabeth Bradley and Lauren Taylor showed that our nation was comparable to peer nations in combined healthcare and social infrastructure spending. But there is an unfortunate reality in this finding, which continues to hold true when the information in Bradley’s and Taylor’s chart is updated to 2022 using the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) comparative database.

Health spending and social spending as a percentage of GDP, by 6 nations with high GDPs

The reality is that the United States not only spends much more than any comparable nation on healthcare, but also markedly underspends those countries on social infrastructure and support for families (e.g., addressing food insecurity and homelessness, drug abuse treatment, paid maternal leave). Americans are increasingly falling through the widening cracks in our social safety net and landing in the hospital emergency department (ED).

The problem with Medicare and physician payment

This same shortsighted misallocation also occurs inside the healthcare system. For more than two decades, Medicare payment policy has starved primary care physicians (as well as nurses and home health aides) who help manage patients’ serious clinical risks and keep them out of hospital EDs.

Medicare, the largest payer for physician services in the nation, has allowed physician payment rates under the Part B Fee Schedule to lag medical practice expenses by 33% over the past 25 years.a The predictable effect has been to undermine private medical practice and drive physicians into more costly hospital employment or corporate practice funded by private equity firms.

Hospitals have filled unmet physician needs in their communities, but at enormous cost to themselves and to society. By early 2025, the average gap between a hospital-employed physician’s salary and the revenue they generate, after overhead, exceeded $300,000.b Yet the federal subsidies that hospitals use to offset some of these losses — facility fees and clinic charges (including so-called “site-of-service” payments) — seem likely to be reduced by Congress in

future years.

Other changes undermining the nation’s safety net

Critically, the recently passed federal budget for FY26 and beyond will exacerbate the structural imbalances in the health system discussed above. Medicaid is the largest payer for substance abuse services in the nation.c

More than 1.6 million Medicaid recipients receiving substance use disorder treatment are likely to lose eligibility because of Medicaid changes under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), potentially disrupting access to treatment and medications that keep them off opioids. Lives will be lost, and more individuals will end up in ambulances headed for hospitals.

Medicaid is also the largest payer for nursing home services in the United States.d And reduced Medicaid funding will likely push many marginal nursing homes out of business, making it increasing difficult for hospitals to place patients into long-term care who are not acutely ill but are too sick to return home.

Likewise, Medicaid is the largest single revenue source (60% of total) for the nation’s 1,359 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), which care for more than 34 million Americans regardless of their ability to pay.e

Combined with the $11 billion in ‘clawed-back’ funding for state and local public health agencies, these reductions will further compromise the public health safety net, leaving hospitals even more isolated as the most expensive providers in their communities.f

All in, it is difficult to imagine federal health policy moving more aggressively in the wrong direction than it has in the past year.

How we can fix the problem

Reducing demand for the most expensive services offers the greatest leverage for lowering health spending. Reducing avoidable hospital admissions and readmissions should be the core focus of any effort to improve the affordability of care. Accomplishing this goal will require the following four steps.

1 Move dollars forward — toward patients before they become patients. Doing this would require both commercial insurers and Medicare to fund non-incremental payment increases for primary care physicians, substance abuse treatment programs, FQHCs and ambulatory surgical and imaging services.

We also need markedly to increase payment for both in-person and virtual mental health services, particularly in inner city and rural areas that face severe shortages of in-person mental healthcare. Any future cuts in hospital site-of-service payments should be redirected into improving Medicare Part B fee schedule payments to primary care physicians.

2 Advocate for federal policies that take pressure off commercial health insurance rates. Employers, public health advocates, physician organizations and other stakeholders must advocate aggressively together to reverse the Medicaid “reforms” enacted in July 2025 by Congress before they take full effect in 2028. This reversal is essential to avoid not only gutting safety-net hospital providers but also kneecapping the “front-end” human services discussed above. Otherwise, OBBBA’s Medicaid reductions, particularly capping and reducing provider taxes and increasing the number of uninsured, will markedly increase employers’ health insurance premiums in future years.

3 Where possible, use existing extensive care management infrastructure to support both provider-sponsored health plans and value-based care risk-sharing arrangements. Health systems that have such an infrastructure should use it — in coordination with FQHCs and primary care practices — to help identify in advance patients at risk for hospitalization and then address both medication and care gaps to keep them out of the hospital. This is a key way health systems can help the millions of people who, under OBBBA, will lose Medicaid or Affordable Care Act health exchange coverage. It will also help alleviate pressure on private health insurance rates and employer costs due to the increase in uninsured patients.

4 Reduce administrative busy work. Health systems and health plans must work together to reduce the administrative overburden that drives up hospital and physician operating expenses and enrages patients. Researchers have found that clinicians now spend as much time documenting care as delivering it.g Health systems and health plans should commit to a policy goal of reducing the time physicians spend documenting care by one day a week so they can see more patients and spend more time with each one.

Today, each insurer has different requirements and payment criteria. Standardizing data requirements across payers in a single, national health insurance claims clearing house — as the economist and Harvard professor David Cutler, PhD, has advocated — could significantly reduce administrative costs.h But the recent Change Healthcare cyberattack has raised questions about the safety, and thus feasibility, of this approach.i McKinsey estimates that better coordination of health insurance payment processes between payers and healthcare providers could save the nation $265 billion annually.j Reducing or eliminating prior authorization and concurrent reviews would also make a major contribution.

Intelligent reallocation of scarce time and dollars is needed

Simply capping hospital rates and separating “undeserving” people from their health coverage will not leave us with a healthcare system fit for purpose. As John Kennedy once said, “We can do better.”

We must refocus our health system on improving health by alleviating the demand for unnecessary care. We must also rebuild our social safety net, from scratch if necessary, so people can live productive lives free from the threat of illness.

Footnotes

a. AMA, “Medicare physician payment continues to fall further behind practice cost inflation,” chart, updated January 2025.

b. Bates, M., and Swanson, E., “Physician flash report: Q1 2025 metrics,” Kaufman Hall, May 7, 2025.

c. Murphy, N., “How the Big, ‘Beautiful’ Bill would undermine access to life-saving substance-use disorder treatment,” CAP, June 18, 2025.

d. Chidambaram, P., et al., “5 key facts about nursing facilities and Medicaid,” KFF, May 28, 2025.

e. Pillai, A., Corallo, B., and Tolbert, J., “Community health center patients, financing, and services,” KFF, Jan. 6, 2025.

f. Winneke, A.N., “Updates to HHS restructuring and funding cuts: impact on state and local public health,” The Network for Public Health Law, April 3, 2025.

g. Tai-Seal, M., et al., “Electronic health record logs indicate that physicians split time evenly between seeing patients and desktop medicine,” Health Affairs, April 1, 2017.

h. Goldsmith, J., and Goldsmith, T., “Why U.S. policy needs to focus on pruning the healthcare transaction thicket,” hfm, May 2024; and Sahni, N., Gupta, P., Peterson, M., and Cutler, D.M., “Active steps to reduce administrative spending associated with financial transactions in US health care,” Health Affairs Scholar, November 2023.

i. Goldsmith, J., “Will the Change Healthcare incident change health care?” Health Affairs Forefront, March 15, 2024.

j. Sahni, N., Mishra, P., Carrus, B., and Cutler, D.M., “Administrative simplification: How to save a quarter-trillion dollars in US healthcare,” executive briefing, McKinsey & Company, Oct. 20, 2021.