Care coordination networks offer path to addressing problems of health inequity

Initiatives to improve access to care and address social determinants of health (SDoH) have been shown to work. To be successful, they need sustained support from all stakeholders within our nation’s healthcare system.

A recently completed initiative in Maryland, called the Health Enterprise Zone project (HEZ), exemplifies how effective care coordination networks can improve quality of care and help reduce costs.

Funded by the Maryland Community Health Resource Commission, and implemented by Prince George’s County Health Department, which is headquartered in Largo, Maryland, HEZ reflected a population health management model in which community health workers (CHWs) are charged with delivering services to coordinate care and mitigate challenges posed by social determinants of health (SDoH).

In its final year, HEZ interventions showed a significant ROI in reducing hospital visits in the community by 47%, while reducing per patient hospital charges for program graduates by 37%. These results underscore the potential benefits of continuous, stable funding of care coordination services by hospital systems and payers.

Project overview

HEZ’s charge was to improve access to care and establish a population health management approach in Maryland’s Capitol Heights community (ZIP code 20743). Capitol Heights, which borders the District of Columbia, has a population of about 40,000 with a high degree of poverty and social need. Inpatient utilization data from the state of Maryland’s health information exchange, the Chesapeake Regional Information System for Our Patients (CRISP), showed that, in 2012, 10% of Capitol Heights residents represented 80% of readmissions from the community at hospitals in Prince George’s County.

About 270 patients in the ZIP code were classified as very high utilizers, in need of multiple services, including SDoH mitigation, primary care services and behavioral healthcare. HEZ was created to address the needs of these patients and to improve care outcomes in Capitol Heights. The implementation process involved four components.

1 Project organization. Prince George’s County Health Department was charged with managing HEZ with input from the Prince George’s Healthcare Action Coalition (PGHAC), the county’s Local Health Improvement Coalition, and a community advisory board. PGHAC’s membership comprised more than 40 community-based organizations, elected officials, healthcare providers and county agencies. The coalition was organized into six workgroups, but only two of those workgroups — those dedicated to chronic disease and access to care — were instrumental in implementing HEZ activities. The PGHAC workgroups served as the source of community input into project plans, implementation and continuous quality improvement.

The community advisory board was composed of a broad cross-section of community residents, providers, public health practitioners, local government officials and patient advocates. The board eventually transformed into the Community Care Coordination Team, which was charged with offering continuous feedback on project workflows and potential quality improvements. The HEZ team members from the county health department comprised a principal investigator, a project director, a nurse manager and a team of CHWs.

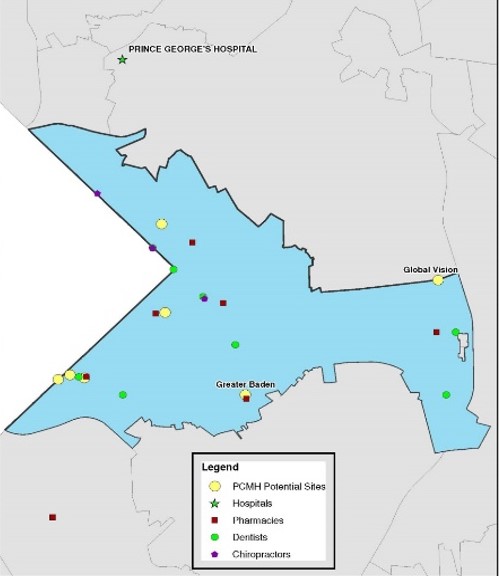

2 Structure for improving care access and coordination. Prior to HEZ, Capitol Heights had been a medical home desert, with few options for primary care services. Through incentive funding from Maryland Community Health Resource Commission, Prince George’s County Health Department established five patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) in the ZIP code with at least one physician and two nurse practitioners per site over the five-year project period. The health department also established teams of CHWs to assist patients with their care navigation and SDoH needs.

Interventions were completed using the Pathways Community HUB Model issued by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[1] CHWs were integrated into hospitals and the newly established PCMHs. The HEZ team worked intensively to understand the needs of the community and to ensure the newly developed pathways adequately addressed those needs. Pathways developed included:

- Asthma

- Behavioral health

- Diabetes

- Employment

- Food

- Housing insurance

- Medical home

- Medical referral

- Medication assessment

- Social services

- Smoking

- Transportation

Pathways also were developed for and implemented by the CHW teams.

3 Campaign for promoting health literacy. The HEZ team invested significant time in building and maintaining relationships with key community members, including elected officials, civic associations, faith-based leaders and residents. Building trust with the community facilitated the success of interventions, including enrolling patients in CHW services and connecting them to care at newly established PCMHs. The county health department also partnered with the University of Maryland’s School of Public Health to implement specific health literacy interventions, including resident-level outreach on key health topics.

4 Network for enhanced information sharing. Prince George’s County Health Department developed a local health information exchange, called the Public Health Information Network (PHIN) to facilitate real time and accurate sharing of patient information among community providers, hospital systems and care-coordinating entities. Enhanced information sharing through the PHIN enabled truly coordinated care, with entities collaborating to address patient needs in a more effective and managed way. The health department also established a team, called the Community Care Coordination Team, in which care-coordinating entities could meet to share case information, with the goals of identifying barriers to implementing effective care coordination and working together to implement systemwide improvements.

HEZ at work: A case example

The impact of HEZ is perhaps best exemplified by the experience of a patient.

A 56-year-old African American female was referred to HEZ after having four hospitalizations and multiple, ongoing health issues, including poor control of her diabetes, no primary care provider, medication non-compliance and depression. The patient lacked transportation, was isolated, did not have family support and was unable to take care of herself and her home without assistance. The patient’s CHW worked with her to complete pathways for connection to a PCMH, transportation assistance, medication assessment, reconciliation, and pictorial aids and enrollment in a diabetes self-management program. The CHW completed specialty referrals for home health, behavioral health, cardiology, pulmonology, nephrology and ophthalmology. The CHW also connected the patient to adult daycare, a personal care assistant and other community group-based interventions. After this intervention, the patient had primary care and specialty visits, received support services and was connected to a community. The end result was that she was socializing and thriving, with no emergency department (ED) visits and no hospitalizations in the six months after enrollment.

HEZ results

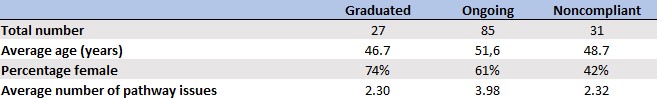

HEZ had a significant impact. The final hospital utilization analysis of the program’s impact looked at 143 participants. Participant characteristics at six months after being enrolled in the program are shown in the exhibit below. The most common SDoH factor mitigated by CHWs was transportation, followed by referral to a PCMH and connection to food assistance, social services and insurance.

Characteristics and status of Health Enterprise Zone project participants, at 6 months post-enrollment

The hospital utilization analysis compared the six months prior to enrollment with the six months post-enrollment. To be included in the analysis, participants must have visited the hospital in the six months prior to enrollment. Hospital data for admissions, ED visits and readmissions came from the Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission and the CRISP.[2] Hospital visits were defined as ED visits and inpatient admissions.

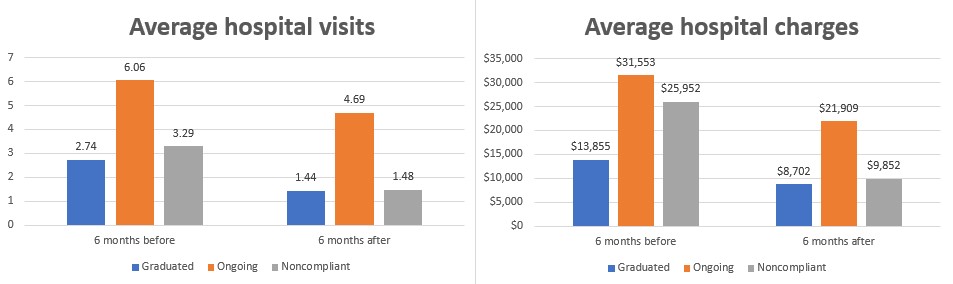

Prior to intervention by CHWs, participants in the project had an average of 4.83 hospital visits per patient, which was reduced by 1.45 visits (30.0%) per patient 6 months post-intervention. The average per patient hospital charges dropped by $10,195 as well, from $26,997 to $16,801 (37.8%). Over the course of the project, this translated to a total cost savings of $1,457,885 in hospital charges and 207 avoided hospital visits.

Results highlighted at the beginning of this article also are illustrated in the exhibit below. In addition, patients who received ongoing services at the time of analysis saw reductions of 22.6% in visits and 30.6% in costs. Even for non-compliant patients, who received partial services or initiated pathways but did not complete them, there were still significant reductions in hospital visits (55.0%) and costs (62.0%).

Hospital visits and charges for patients participating in the Health Enterprise Zone initiative

A call to action

HEZ was funded by a time-limited grant, and the services disappeared when it ended. Despite substantial cost savings to hospital systems and payers, no additional funding was directed back to Prince George’s County Health Department or care coordinating entities. To sustain these services, the health department has applied for and received additional grants, each with their own requirements, reporting and time limitations.

The project’s experience shows that effective care coordination can result in improved care quality and reduced costs. However, effective care coordination is only sustainable when cost savings are invested back into care coordination infrastructure.

Building a modern healthcare system will require payers to cover the cost of care coordination services and hospital systems to use a portion of their community benefit dollars to cover the cost of CHW outreach services, lifestyle change program fees and other SDoH-related expenses. Only through joint implementation of a coordinated care coordination system can our nation achieve the quality and cost metrics that benefit everyone – payers, health systems and patients.

Footnotes

a. AHRQ, Pathways community HUB manual: A guide to identify and address risk factors, reduce costs, and improve outcomes, January 2016.

b. Gaskin, D.J., Vazin, R., McClearly, R. Thorpe, R.J. “The Maryland Health Enterprise Zone initiative reduced hospital cost and utilization in underserved communities,” Health Affairs, October 2018.

Demographics of Prince George’s County, Maryland

- 967,201 residents and growing (12% over the past decade)

- 59.1% Black, non-Hispanic

- 21.2% Hispanic

- 11.3% White, non-Hispanic

- 4.3% Asian, non-Hispanic

- 23.6% of residents born outside United States

- Large geographic area (499 square miles) with urban, suburban and rural areas

Map of Capital Heights health enterprise zone area