David Johnson: Why healthcare’s cupboard is bare — its funding gravy train has run out of steam

Gravy train is a railroad term that originated in the early 1900s. It described a well-paid train run that didn’t require much effort. In modern parlance, speakers use it to describe easy-to-do tasks and cushy situations.

The problem with gravy trains is that riding them too long engenders lazy, sloppy and wasteful behaviors. New York City discovered this consequence the hard way. Decades of overspending, over-borrowing and lax financial oversight, in combination with a stagnant national economy, triggered a fiscal crisis in 1975. The city had a major operating deficit, could not borrow in the debt markets and begged the Ford Administration for assistance.

On Oct. 29, 1975, President Gerald Ford stepped to the podium at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., and declared he would veto any bill providing federal bailout assistance to New York City. The next day’s New York Daily News distilled the President’s pronouncement into an iconic and infamous headline: “Ford to City: Drop Dead.”

Although nowhere near as obvious but perhaps just as dire, American society is sending a similarly austere message to its beleaguered hospitals. Despite the sector’s financial woes, there’s no incremental relief coming. It’s time for healthcare to get off the gravy train and deliver on the promise of value-based care.

A new, more parsimonious funding paradigm has emerged. After decades of consuming an ever-larger percentage of the American economy, healthcare’s share of the economic pie is shrinking. Healthcare’s gravy train has run out of steam. Macroeconomic realities are driving this paradigm shift. The numbers don’t lie.

Inflection point

The term inflection point has taken on ambiguity due to inexact usage in recent years, to the point that some argue it has lost its usefulness. For example, it’s even on a 2023 list of banished words identified by Lake Superior State University. As used here, however, the term reflects its original — and I would suggest, still useful — meaning in reference to the point on a mathematical curve where its curvature changes direction. This shift occurs before the curve achieves its peak, with a decline in its rate of increase (its slope) as it nears the peak.

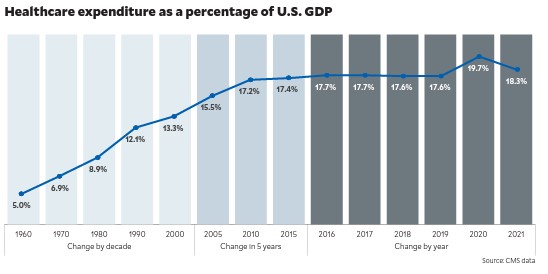

The right way to measure the funding curve for healthcare expenditures is to plot its relationship as a percentage of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP). The chart below depicts how healthcare’s share of the U.S. economy increased dramatically from 5% in 1960 to an inflection point at 17.2% in 2010 as healthcare expenditures had been growing faster than the overall economy.

By 2010, healthcare’s annual growth in expenditures began to mirror that of the overall U.S. economy. Absent COVID-19, there is good reason to believe healthcare expenditures as a percentage of the national economy would have continued to see a very gradual decline (already apparent between 2017 and 2018).

Impact of the pandemic

The pandemic forced a lockdown of the global economy. In response, the federal government pumped hundreds of billions of dollars into the healthcare economy, including $185.5 billion in direct financial support to hospitals and other healthcare providers.

U.S. healthcare expenditure grew by an astonishing 10.3% in 2020 to $4.12 trillion, according to CMS.a Healthcare’s share of GDP increased from 2019 to 2020 by an unprecedented 2.1 percentage points, from 17.6% to 19.7% (an increase equating to roughly $500 billion). Many incumbents misread the government’s emergency COVID funding as long-term support for existing healthcare funding levels and business practices. This was wishful thinking.

There was bound to be some correction to 2020 healthcare expenditure levels. As detailed in its March 2022 forecast, CMS expected the rate of increase in national health expenditures during 2021 to drop to 4.2%, accelerate to 4.6% in 2022 and remain above 5% annually through the end of the decade.b Don’t take that forecast to the bank. It misses the inflection point.

Traditional expenditure analyses, like CMS’s, miss the dynamism that is changing healthcare’s underlying supply-demand relationships. This dynamism explains, for example, the push into healthcare by big retailers like Amazon. The market is reorganizing to offer higher-value, customer-friendly products and services. This is the real threat to status-quo provider and payer business models dependent upon fee-for-service (FFS)/administrative-services-only (ASO) contracting.

Here’s what actually happened in 2021. Healthcare expenditures did not increase 4.2% as predicted by CMS. Instead, healthcare spending rose just 2.7%. Healthcare’s percentage of the national economy declined a staggering 1.4 percentage points from 19.7% to 18.3%.c

The federal government funded almost all its emergency COVID expenditures with debt. As a result, the ratio between federal debt and U.S. GDP grew from 107% in 2019 to 128% in 2020. Real economic growth slowed to 2.1% in 2022. There is significant danger of a recession in 2023. The federal government, even if it wants to, doesn’t have the capacity to provide more emergency funding to healthcare providers. Its cupboard is bare.

Beggars and choosers

What does this macroeconomic analysis have to do with hospitals? According to Kaufman Hall’s January National Hospital Flash Report, 2022 was the worst year financially for hospitals in decades. Half of U.S. hospitals lost money as expenses grew faster than revenues.

To add salt to the wounds, commercial health insurance premiums only increased 1% and 2% in 2022 for family and individual plans respectively. With inflation hovering above 6%, commercial insurers are not granting significant rate increases to hospitals.

These macroeconomic trends involving GDP growth, debt, productivity and inflation explain why American society is unwilling and incapable of shifting resources disproportionately into healthcare despite the industry’s urgent pleas. No external funding sources will ride to healthcare’s rescue. Expect economic pressure on hospitals to intensify.

This dire reality would be bad enough if healthcare were delivering good outcomes, but it’s not. In a recent commentary, 4sight Health’s David Burda makes the compelling observation that the health status of residents in other advanced nations is dramatically better than that of U.S. residents.

In his keynote address for its biannual Mindshare Conference, Intermountain Healthcare President and CEO Rob Allen observed that preventable acute conditions account for 27% of spending and that waste of various kinds account for 25% of healthcare spending. Allen believes this expenditure pattern is both unacceptable and unsustainable.

“Patients shouldn’t need a compass to navigate the health system, and we should help them start that navigation process before they get sick,” Allen said. “Better health demands that we partner with people to get a step ahead of disease, keep them healthy and avoid unnecessary and expensive acute interventions. People simply want to be healthy. So we must ask ourselves how we can make that simpler and achievable for them.”

Backlash on the industry

Healthcare’s bad macroeconomics and historic lack of value creation have triggered its funding inflection point. It has led to a “reverse Robin Hood” moment: After stealing resources from the rest of American society for 60-plus years, incumbents are now experiencing a backlash. American society is now repatriating some of its lost wealth.

Expect healthcare’s share of the national economy to flatline or decline through the balance of the decade. This is good news for the U.S. economy and the American people. As a nation, we need less healthcare and more health. However, it’s not going to be easy for healthcare incumbents to adjust to this new normal — a phrase banished by Lake Superior State University in 2022. Remaining competitive within a shrinking and dynamic marketplace takes skill and courage.

A ‘tough love’ message healthcare needs to hear

With the benefit of hindsight, many now believe that President Ford’s tough love — if not always entirely accurately reported — message to New York City was critical to its financial turnaround and subsequent recovery. Henry J. Stern, a former parks commissioner and city councilman, observed that “Ford was good for New York, because he made us clean up our act.”

Entwined within healthcare’s new funding reality is a similar tough love message. It’s time for the healthcare industry to clean up its act and address its dysfunction. Financial sustainability for hospitals and health systems must come from overhauling their bloated and ineffective business models. Health systems have a choice. In value there is salvation.

Footnotes

a.CMS.gov, “National health spending grew slightly in 2021,” Press release, Dec. 14, 2022.

b. CMS.gov, “CMS Office of the Actuary releases 2021-2030 projections of national health expenditures,” Press release, March 28, 2022

c. FiscalData.treasury.gov, “What is the national debt?” Updated daily.