Monetizing Data: The Key to Realizing the Value of Data Analytics

The value of data analytics is in many ways unquantifiable, but healthcare organizations that understand how data can be monetized will appreciate why investing in such assets is so critically important.

In a 2018 industry outlook survey conducted by HealthLeaders Media, 65 percent of respondents reported that their most significant area for investment would be in clinical analytics, with the next most frequently cited investment areas being electronic health record (EHR) interoperability (cited by 49 percent of respondents), mobile health/technology (44 percent), financial analytics (42 percent) and data-driven knowledge of patient health factors (40 percent). a As these investments begin to generate positive returns for many organizations, it is likely they will continue to garner similar amounts of interest throughout 2019.

These investments are producing vast information assets that have economic significance for healthcare organizations beyond that of traditional metrics. And as foundational pieces of a new healthcare information economy, they are introducing complexities—including ethical concerns regarding issues such as patient privacy—that healthcare organizations must consider as they seek to apply these boundless new data resources to realize their full potential. As healthcare organizations tackle this challenge, their ability to understand and communicate the economic impacts of their information assets will require a departure from traditional measures of success and a focus on new concepts and approaches, including the idea of data monetization, which is a primary focus of this article.

Before delving in to this concept and its application, however, it is helpful to review the factors driving change and the reasons traditional ROI measures are insufficient to healthcare organizations’ investments in data analytics.

Change Factors

Although the mission of health care has remained largely unchanged over the years, the business of health care has changed dramatically. Since the advent of managed care, the business of health care has necessitated a clinical, financial, and operational transformation, which has intensified in the era of value-based care. And although a hunger for data has always been a characteristic of the healthcare business climate, nothing compares to the appetite for data and analytics that we see today. For better or worse, the healthcare industry is outpacing its peers in expanding its data footprint. A 2018 report by International Data Corporation (IDC) projects that the volume of big data will increase faster in health care over the next seven years than in any other industry. b

This transformation has been driven largely by the following factors:

- The digitization of health care, from the EHR to the Internet of Things (IoT), including wearables, sensors, telehealth, and mHealth apps

- The drive for more evidenced-based versus experience-based treatment and preventive care

- Consumerism and personalized medicine

- The emergence of new and alternative payment models in pursuit of value-focused care

- Revenue-driving consolidation

- The appreciation of data/information as valued assets, even if not yet recognized as such under the generally-accepted principles of accounting

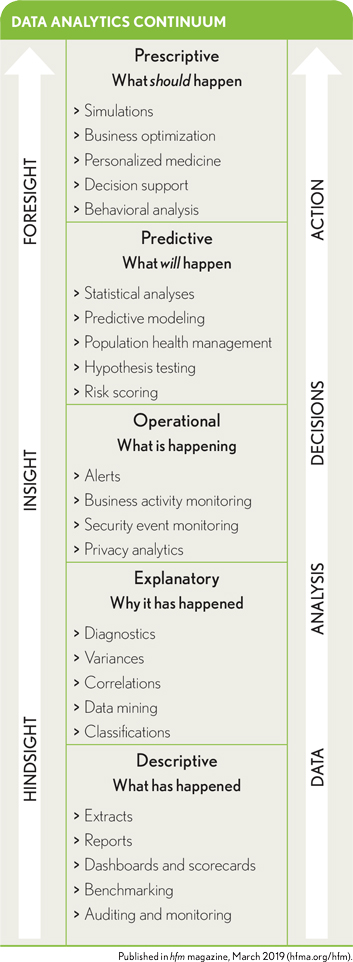

To date, many of the healthcare analytics “wins” have been achieved based on the implementation of descriptive analytics capabilities. As the industry’s capabilities advance along the analytics continuum, the value of the investments in data and analytics, the insights generated, the information assets created, and the outcomes realized will fuel the healthcare information economy further.

Data and information also are unique among healthcare organizations’ assets in that they are reusable and do not depreciate as other assets do. In fact, the value of longitudinal patient data and the ability to analyze those data may increase over time, enabling improved population health management and delivery of personalized medicine.

Limitations of Traditional Metrics

The investments healthcare organizations have made in the systems that create, transform, share, and store data and information assets have dominated organizational budgets for the past 20 years. And measuring the return on these investments has continued to be top-of-mind for executive teams and boards of directors. Yet current approaches to measuring ROI are not well-suited for the emerging healthcare information economy.

The problem is that traditional, transactional ROI financial modeling (money spent compared with revenue captured) does not always fit as a best measure of value regarding investments in data foundations and analytics. Other methods of measuring value often employed look at effect on cost, on revenue, on performance improvement/efficiencies, on competitive advantage, and on speed-to-value. Although these methods are useful and can yield quantitative outputs, they also tend to indicate only nonfinancial, positive net outcomes, such as better patient outcomes, reduced patient pain, and patient satisfaction. These are inarguably important outcomes, but the inexact math involved in trying to quantify them frustrates more than it satisfies.

The ROI of data and analytics investment is further complicated by the fact that the investing entity may not be the entity that receives the value from the investment. For example, a health system’s investments in healthcare IT may result in patients being treated at a lower cost. Depending on the payment model, however, the hospital may not be the entity that accrues the economic benefit; it may be the insurer or the patient.

The challenging question posed by many senior leaders and board directors is, “What are our data worth?” The answer to this question is largely dependent on how the data will be used.

Efforts to address these concerns have led many organizations to rethink their approaches to understanding and communicating the value of investments in data and analytics. There are many talented data scientists and analysts across the industry working to make measurement more precise and rigorous and to establish valuations for things that historically have been difficult if not impossible to measure, such as reduced pain and increased patient loyalty. Health care could also look to industries that have more mature data and analytics capabilities for lessons previously learned and models worthy of adoption.

Monetization of Digital Assets

Monetizing information as an asset is an effective way to reconcile the healthcare information economy with the value-based healthcare financial economy. The term data monetization is defined as the use of data to create economic value by driving new revenue or reducing costs.

Over the past decade, with the rise of big data and supporting IT infrastructures, the principal objective of analytics programs has been to enhance decision-making. Measuring the financial benefit of this improved decision-making has been the target of ROI efforts. Purposeful monetization is a recent development. Most organizations do not passively “back in” to data monetization; they establish specific objectives to realize economic value from their investments in data and analytics. Data monetization is almost always an element of a data strategy laser-focused on defining the value of data to the organization, to its customers, and to its partners.

In his book, Infonomics, Douglas Laney, a vice president and distinguished analyst with Gartner, introduces 11 drivers of data monetization: c

- Increasing customer acquisition/retention

- Creating a supplemental revenue stream

- Introducing a new line of business

- Entering new markets

- Enabling competitive differentiation

- Bartering for goods and services

- Bartering for favorable terms and conditions, and improved relationships

- Defraying the costs of information management and analytics

- Reducing maintenance costs, cost overruns, and delays

- Identifying and reducing fraud and risk

- Improving citizen well-being

These drivers are most frequently classified into two types of monetization: direct and indirect. Examples of direct monetization include bartering or trading with information, selling organizational data, selling organizational analytics, and developing information-enhanced products/services. Examples of indirect monetization include enhancing existing products and services, reducing costs, improving productivity, efficiency and performance, introducing new products/services, improving impact through personalization, entering/developing new markets, and building/strengthening partner relationships.

Although there is certainly some harmony between drivers of ROI measurement and data monetization, the latter is distinguished by the following:

- Inventorying data assets and understanding what data are valuable

- Identifying consumers for an organization’s data (i.e., its “change agents”) and understanding their objectives

- Preparing data for maximum impact (which might include enrichment)

- Mobilizing data in the most effective way to consumers

Measuring Economic Value

There is a growing awareness about data monetization principles and strategies in health care, with increasing adoption and implementation by hospitals and health systems. Most of the efforts to date involve indirect monetization—involving cost reduction and performance improvement, for example. Some organizations are introducing more advanced indirect monetization in the form of new products and services, new markets, new customers.

See related sidebar: Allina Health: Reducing Variations in Clinical Care

Most investment and activity in data and analytics have been spurred by the need to succeed under value-based care. Examples include efforts focused on population health management, personalized medicine, and risk-based contracts and incentives. That said, consumerism and the drive to engage patients through digital solutions and an overhauled patient experience are quickly becoming top priorities.

The case study sidebars throughout this article exemplify the principles, emerging practices, and complexities in these moves to monetization.

Monetization Cautions

Areas where healthcare organizations should exercise caution with respect to monetizing data assets include “smart” equipment, business associate and data use agreements, and cost of data preparation, accounting for unmeasurable factors.

‘Smart’ equipment. Nearly every piece of equipment or device introduced into a patient care setting today is “smart,” capable of collecting data that vendors are eager to monetize. The practice of “bartering” is common as vendors introduce highly preferred pricing in exchange for access to the data their devices collect. Bartering often is viewed as the “low hanging fruit” of direct monetization. Simply put, it is a form of data selling.

“Some organizations have established clear policies that they will not trade data for services under any circumstances,” says Shannon Fuller, director of governance advisory services for Gray Matter Analytics in Chicago. “Clarifying, understanding, and enforcing organizational data ethics, particularly in the context of direct monetization (selling data), is becoming increasingly important. Are those ethics situational depending on the data or service line in question? Are there clear processes in place to consider these arrangements? We know not all data is created equal, but healthcare organizations, particularly provider organizations, have very little experience in this arena.”

These prospective arrangements call on healthcare organizations to consider the question “What are our data worth?”—unless organization policy flatly rejects such arrangements.

Business associate and data use agreements. The concern with master services, data use, and business associate agreements is that an organization might be at risk for having its data sold, misused, or monetized beyond its intended purpose, or used to advance someone else’s product or service development efforts without its knowledge because the data use provision in the agreements is too loosely written. Such occurrences are far too common.

As part of the procurement process, and ideally as early in the procurement process as possible, any proposed data-use language and/or agreements should be reviewed thoroughly. The contracting entities should have a clear and common understanding of information use rights permitted. Any restrictions also should be clearly articulated.

Fuller cites the experience of a healthcare organization that learned this lesson the hard way: “The organization agreed to provide patient data to a physician who, in exchange, promised to share the outcome of his research back to the organization. The research was of strategic interest to the organization. The organization executed its standard business associate agreement [BAA] with the physician accordingly. The physician developed a software application based on his research, sold it, and the organization received no compensation.”

Although none of the organization’s data were sold (which is prohibited in a standard BAA), the physician monetized the organization’s data indirectly by creating a product that would otherwise not have existed and was made possible only by the organization’s data.

See related sidebar: UPMC: Expanding Organization Reach via Telemedicine and Virtual Care

Fuller states, “The organization’s BAA now has standard language that restricts a business associate from developing a service or application based on any aspect of the data sharing relationship governed by the BAA.”

The costs of data preparation. These costs often are overlooked and uncalculated. Healthcare data rarely come from a source system ready to use in support of analytics. Preparing data for analytics is a cost that organizations all too rarely consider in either ROI or monetization analyses. When asked, data scientists and data analysts report that at least 40 hours of data preparation are required for even the smallest and straightforward net-new or ad hoc analytics requests. And for artificial intelligence and machine learning initiatives, the preparation required may be hundreds of hours.

Accounting for unmeasurable factors. What currently cannot be measured or is not universally accepted as being quantifiable (e.g., patient satisfaction, the value of reduced pain, the value of speed to diagnosis) absolutely counts in the monetization equation. As the industry accumulates more data, and as the data become more diverse, critical connections will be made and hypotheses about value will be proven and quantified through the data. Until then, organizations should employ processes and techniques to capture these data, anecdotally or in other ways, and then classify it in some practical way, while continuing to ask probing questions to find correlations to value. Health care is not retail, and there are no loyalty cards—at least, not yet. But the focus on consumerism will surface new data that will be instrumental in determining the economic value of things that simply cannot be measured today.

See related sidebar: UVM Health Network: Building an Industry-Leading Supply Chain

A Strategic Asset

Healthcare data are strategic assets with tremendous potential to improve an organization’s top and bottom lines. As the business of healthcare delivery becomes increasingly value-based and competitive, data and information assets, and how they are employed, will be the differentiators between the industry leaders and those that fall behind. Expanding measures for data and analytics beyond traditional ROI to monetization requires an organization with a truly data-driven mindset and a purpose-built data strategy. Whether an organization intends to leverage data and analytics for internal performance improvement or market differentiation, it can remain securely on the path to competitive advantage by framing and executing its initiatives with monetization principles that recognize data as an essential strategic asset.

Footnotes

a. Bees, J., Annual Industry Outlook: Exploring Investments and ROI, Intelligence Report, HealthLeaders Media, January-February 2018.

b. Reinsel, D., Gantz, J., Rydning, J., Data Age 2025: The Digitization of the World From Edge to Core , whitepaper, IDC, November 2018.

c. Laney, D., Infonomics: How to Monetize, Manage, and Measure Information as an Asset for Competitive Advantage,Gartner, September 2018.