HEALTHCARE 2030: SDoH convener or leader?

Hospitals and health systems are still trying to figure out their role

By Jeni Williams

HFMA Contributing Writer

What started as a goal in 2019 to reduce avoidable emergency department (ED) visits by 8% among one health plan’s Medicaid patients in two Utah counties actually led to a 34.2% drop in such ED visits. The effort also expanded access to behavioral health services and built a deeper understanding of patients’ whole-health needs.

The improvements came as a result of Intermountain Health in Salt Lake City launching a three-year demonstration project through the Alliance for the Determinants of Health. The alliance is a partnership between Intermountain’s health plan, Select Health, and key stakeholders at the health system and at the community and state levels. The alliance sought to become a model for addressing social determinants of health (SDoH), with screenings administered in ambulatory settings and in EDs to determine: What social needs do these individuals face that affect their health? How can gaps be closed to improve health and reduce cost of care?

“The screenings uncovered a huge need for dental care, transportation services and access to affordable housing,” said Tiffany Capeles, chief equity officer, Intermountain Health. “We also identified struggles with food insecurity and the need for medication assistance and behavioral health.”

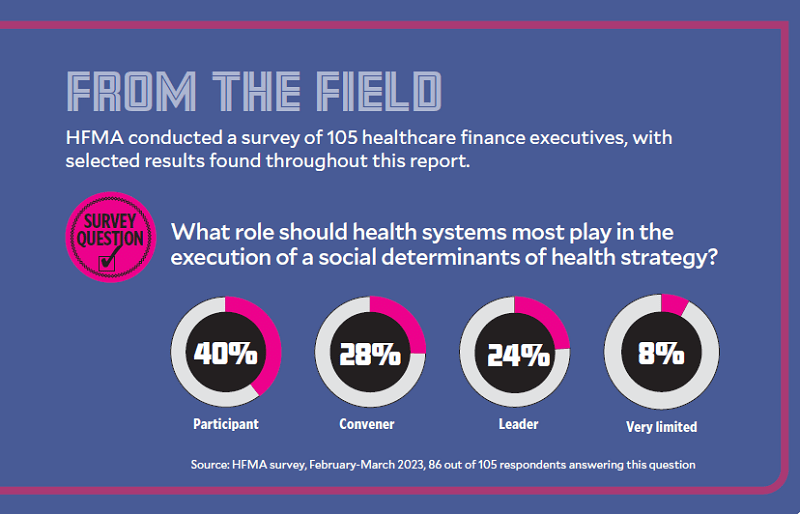

SDoH has become an area of strategic focus for health systems across the country. About 24% of healthcare finance professionals surveyed by HFMA believe health systems should lead the execution of SDoH strategy in their communities. Nearly 28% believe health systems should serve in the role of convener, bringing key stakeholders together to address the social drivers that contribute to health disparities and inequities, from food insecurity to lack of reliable transportation or stable housing.

— Tiffany Capeles, chief equity officer, Intermountain Health

As Utah’s Alliance for the Determinants of Health prepares to release a report on its findings, based on 20,000 screenings and nearly 5,000 unique service episodes over a two-year period, its work around SDoH has expanded into 19 counties in Utah, with 230 community partners and support from community health workers.

“We can’t solve for everything,” Capeles said. “There are some things that might be a little beyond the reach of our health system. We’re analyzing our data to understand where there are gaps that affect health and well-being. Where there aren’t ways to address these challenges, we’re challenging ourselves to ask, ‘Why not?’

“For instance, we know social isolation and loneliness have a direct impact on health. How can we work with our interfaith communities and community organizations to help address these issues?”

The ability to pair people in need with services that could help close these gaps also varies by geography.

“We are able to connect people with resources a lot easier in our urban settings than our rural settings,” she said. “Especially in very small communities — those with just 1,500 people, for example — the infrastructure is not there. In those areas, residents often call family and friends for help with transportation because they are so close-knit and don’t have other resources they can rely on.”

More Active Role For Hospitals

Today, socioeconomic factors alone affect 47% of health outcomes, recent research shows. And another study found just 20% of county-level variation in health outcomes stems from differences in clinical care. SDoH influences 50% of health outcomes.

These are just some of the reasons why federal officials are pushing health systems to take an active role in addressing SDoH. In 2024, the CMS will require hospitals to screen for social drivers of health and report the positive rate of SDoH screenings, or the percentage of patients screened who have at least one social risk factor. Hospitals may voluntarily report this information in 2023.

And the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has designated SDoH as a strategic focal point, given the impact the conditions in which people live, learn, work, play, worship and age have on health outcomes, functioning and quality of life.

“There’s so much that we can do right now once we accept that we’re in this mess together, and we embrace the fact that we are the guides we’re looking for,” Thomas Fisher, Jr., MD, MPH, an ED physician for UChicago Medicine and author of The Emergency: A Year of Healing and Heartbreak in a Chicago ER, told attendees of the HFMA Annual Conference this past June.

But there currently is no common road map for addressing SDoH at the health system level, nor is there guidance around how to fund these initiatives or build the right partnerships to make a meaningful impact. As healthcare leaders determine their organization’s path forward, they must develop an SDoH strategy that is grounded in data and builds upon lessons learned from first movers in this area (see sidebar, left).

One of the biggest challenges in addressing the whole-health needs of the community lies in developing standardized processes for data collection. From there, health systems need strong analytics to dig deep into the data and determine where to focus.

“Everyone has the potential to have a need,” said Kevin Halbritter, MD, chief medical information officer, West Virginia University (WVU) Health, and vice president of population health, West Virginia University School of Medicine. “It’s making sure that you cover all the different facets of healthcare that involve patients and identify the right interventions at the right times to connect them to the resources that can make a difference.”

And even when health systems do standardize their approach to SDoH screenings, the view health systems gain into the social needs of their communities depends on how comfortable patients feel disclosing this information.

“Social needs are very personal,” said Jurema Gobena, MPH, system director, social care integration for Chicago-based CommonSpirit Health. “You’re asking very intimate questions of patients, and they’re not necessarily used to having those questions asked by a physician or nurse, Gobena said.

“You’re limited by what people want to disclose or how well people are trained to tease out the answers, which means you’re never going to get a 100% accurate data set across all the populations you serve. But screenings like these put us in a good position to optimize our approach over time so we can learn to engage patients in ways that help them feel more comfortable disclosing that information.”

At CommonSpirit Health, SDoH data currently are collected in clinics and CommonSpirit’s managed services organization. Over time, the health system plans to expand data collection to its EDs, inpatient areas and more, “because patients are never just in one place,” Gobena said.

— Jurema Gobena, MPH,

system director, social

care integration for

CommonSpirit Health

CommonSpirit Health team members created the “Connected Community Network” five years ago to connect community partners, healthcare organizations and government agencies that are working to address specific social needs. It’s a model that creates an infrastructure for all community partners to work collaboratively together to maximize collective impact and center care in the community.

Outside in Approach

Case Studies: 3 health systems using tech on SDoH to improve health

Building and sustaining internal momentum for social determinants of health data collection, a key component of SDoH management, depends largely on a health system’s ability to follow through on the insights they receive.

— Kevin Halbritter, MD, vice president of population health, West Virginia University School of Medicine

“You have to have processes in place to be able to connect patients to resources that meet the needs that are identified,” said Kevin Halbritter, MD, vice president of population health, West Virginia University School of Medicine. “You can’t just collect the data. You have to act on it.”

Just as important is connecting patients to resources available in their community, where possible. That can be particularly difficult when patients travel for care.

“We have patients come to our clinic in Morgantown (West Virginia) from two to three hours away,” Halbritter said. “A nurse cannot be expected to know all the resources available within her own town, let alone in another part of the state. We’re trying to make sure our nurses are not bound by local knowledge when it comes to addressing social determinants of health.”

WVU Medicine team members have moved from compiling lists of resources on their own to using a nationally focused website called “FindHelp,” where staff can input a patient’s ZIP code and find an organization or service to match a patient’s need, including such things as food pantries, transportation assistance and shelter.

“We’re trying to integrate tools like these in our EHR, but this is a stepwise approach that helps team members connect as many patients as possible with resources that meet their needs,” Halbritter said.

Claudia Fegan, MD, chief medical officer, Cook County Health, remembers when team members relied on a purple book with staff-compiled lists of homeless shelters, food pantries and other resources. One of the many challenges with this approach was ensuring the information was up to date.

“We would often reach out to our social workers to ask, ‘Does this shelter still exist? Is this food pantry still open?’” Fegan said. At times, staff who have an interest in a particular need will take the lead in building a more efficient approach.

“I had a physician whose sons became very interested in food pantries and actually created an app that each of our physicians could have on their phone called ‘Got Food,’” Fegan said. “It allows you to see what pantries are within a mile radius of a particular address.”

At the height of COVID-19, Cook County Health partnered with local hotels to secure safe shelter for people with unstable housing who contracted the virus.

“We’ve found that it’s actually cheaper to find housing for patients with acute care needs than it is to admit them,” she said. “Not only is temporary housing cheaper than hospitalization, but patients with unstable housing are also more likely to have poor outcomes as a result of the frequency with which they change locations.”

Intermountain Health adopted a technology platform called “Unite Us” to create a coordinated network that connects healthcare, mental health and social services partners — including state and local health departments and federally qualified health centers — with the resources they need.

The network first began to meet the needs of residents in Washington and Weber counties in Utah and is now available statewide. The health system also looks for ways to build capacity in areas such as behavioral health, where virtual care helps meet the needs of children and those living in rural communities, and intimate partner violence. The latter carries a focus on local community partnerships that strengthen Intermountain’s ability to identify and respond to potentially life-threatening domestic situations.

“‘Unite Us’ gives us a sort of clearinghouse for all of the requests we receive based on patients’ social needs,” said Tiffany Capeles, chief equity officer, Intermountain Health. It allows Intermountain to track whether or not the dots get connected.

“It’s a collaboration with a number of local- and state-level partners that helps us connect with one another through a single network to pair people with the resources they need without putting the onus on providers or clinics or patients to find these resources themselves,” she said.

Lessons learned from leaders in SDoH

With so much at stake and so little standardization in approach, how can healthcare leaders design an effective strategy for addressing SDoH? Here are five suggestions from organizations with experience in this space.

- Be mindful of the SDoH data that isn’t captured, as this could skew your big-picture view of a population’s social needs. In Alaska, for example, “Sixty-five percent of our state is considered an undetermined health equity zone,” said Anne Zink, MD, chief medical officer for the state, during a HIMSS presentation in April. “You always need to ask yourself, ‘Who are the undetermined?’” Without this data, organizations miss opportunities to eliminate inequities in care and health resources.

- Embrace opportunities to leverage data for a collective approach to addressing SDoH. “As health systems, we sit on mountains of data,” said Tiffany Capeles, chief equity officer, Intermountain Health. “We have an obligation to use this data to determine where gaps in social needs are. Then, we can work with local governments or community partners to make a meaningful impact. We perpetuate harm by not sharing that information.”

- Look for entrepreneurial opportunities to strengthen SDoH. “Where can we leverage our chambers of commerce and Small Business Administration to say, ‘Hey, there’s a need here. How can we as a community build a viable model for addressing this need, whether it’s grocery delivery or transportation to medical providers or care for the elderly?’” Capeles said. “There are so many opportunities for a business to help bring the right player to the table.”

- Lean into the expertise of community health workers. “Many of these professionals come from the communities they’re trying to serve,” said Claudia Fegan, MD, chief medical officer, Cook County Health. “They have a deep knowledge of all the local players, and they have the opportunity to make a big impact on the social determinants of health.”

- Understand that your health system’s role isn’t to solve everything. “Your role is as a stakeholder and partner,” said Jurema Gobena, MPH, system director, social care integration for CommonSpirit Health. “When you accept that role and understand that you could be a catalyst for change, you are much better positioned to build trust and partnerships within the community you serve and let the community lead,

making sure they have the capacity and tools and resources to meet these needs.”

Leveraging the science of kindness for health equity

“Quiet acts of humanity,” such as taking the time to form a bond with patients prior to surgery, demonstrate compassion for a patient’s health and social needs, and offer reassurance after a diagnosis, can improve health outcomes and medication adherence and reduce the need for sedatives before a procedure, researchers have found.

The link between compassion and outcomes is one reason why CommonSpirit Health launched the Lloyd H. Dean Institute for Humankindness & Health Justice in December 2022. It’s an initiative that tries to tap into the power of human kindness to treat the social causes of poor health, advance health justice and accelerate health equity.

The institute is named after Lloyd Dean, former CEO of CommonSpirit Health and a nationally recognized healthcare leader, who was driven to close gaps in care for vulnerable populations based on his experiences growing up without regular access to care in rural Michigan. Dean retired in 2022.

“I heard Lloyd Dean speak many years ago, and something he said stuck with me: that one of the most innovative things he’s seen in healthcare today is that kindness has the ability to heal,” said Alisahah Jackson, MD, president of the institute. “That resonated with me so much.”

By galvanizing staff at CommonSpirit Health — one of the nation’s largest health systems — to demonstrate kindness and compassion in their interactions with patients, Jackson believes the organization could make a significant impact on community health in the 22 states the health system serves.

“We know from the science that altruism actually leads to better health outcomes,” Jackson said. “It reduces chronic inflammation; it reduces stress; it reduces risk for cardiovascular disease and dementia. At a time when we’re seeing some of the lowest levels of civility our nation has experienced in decades, now is the time to remind people that kindness not only helps improve the health of others around them, but their own health as well.”

Pinpointing the needs of the most vulnerable

— Claudia Fegan, MD, chief medical officer at Cook County Health

At Cook County Health in Chicago, which provides care to half a million people, including a large Medicaid managed care population, the health system discovered the importance of asking all patients questions about their relationships in the home back in the 1990s.

“We found a lot of people felt unsafe in their space,” said Claudia Fegan, MD, chief medical officer, Cook County Health. “One of our emergency room physicians was stunned when she discovered people of all economic strata had been victims of domestic abuse. She realized if you don’t ask the question, you can never assume. It opened the door to a lot of conversations that gave us a deeper understanding of the prevalence of problems people face in the home.”

Later, in the early 2000s, Cook County Health began to add questions around food insecurity.

“We were surprised to learn that if someone in the home was over the age of 65 or under the age of 6, the odds of food insecurity were much higher than for other populations,” Fegan said. “We started to realize that maybe there were other questions we should be asking, too. If people don’t have safe housing, if they don’t have adequate food, if they don’t have safe transportation, these all become health issues. And in Cook County, we wind up seeing the results of the failure of society to address these problems.”

These experiences informed Cook County Health’s approach to asking all patients questions around social determinants of health (SDoH), regardless of income level. All staff are trained on how to ask these questions because the quality of the data collected depends on the skill of the interviewer and how a question is phrased, Fegan said.

But standardizing SDoH screenings is complex work in large systems. At CommonSpirit Health, which operates more than 700 care centers across 21 states, there are “multiple EMRs with multiple ways of asking questions around patients’ social needs,” said Jurema Gobena, MPH, system director, social care integration for CommonSpirit Health.

While the data are pulled into a social determinants dashboard to gain a community-specific, regional and national view, “My colleagues in IT would say it takes quite a bit of money and analytical power to do that across all of our EMRs,” she said. “It’s a huge challenge for us.”