Building skilled nursing relationships to improve hospital length of stay

To successfully bring down average length of stay (ALOS), health system management must combine their efforts to improve performance with their efforts to align themselves more closely with skilled nursing providers.

The timely discharge of patients to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) remains a significant concern for health system leaders. There have been some signs of improvement: Just over 40% of respondents to Kaufman Hall’s 2023 State of Healthcare Performance Improvement survey indicated that inpatient average length of stay (ALOS) had decreased over the past year. But that follows the results of the 2022 survey, in which nearly 70% of respondents reported an increase in inpatient ALOS. For a majority of the survey respondents in the more recent survey, inpatient ALOS had either not improved or had gotten worse over the past year.

The impact of heightened inpatient ALOS was called out in Moody’s Investors Service’s 2024Outlook for Not-for-Profit and Public Healthcare: “ALOS is likely to remain at higher than historical levels. Healthcare systems with minimal access to post-acute-care settings will be particularly vulnerable to elevated ALOS, as many patients will need to stay in the hospital until they can be discharged to an appropriate post-acute-care setting. An elevated ALOS will keep labor costs high and may constrain hospital bed capacity, potentially curbing revenue.”a

Ensuring that inpatient discharge processes are optimized will remain an important focus of health system performance improvement efforts in reducing ALOS. But these efforts will be diminished if there is not a sufficient supply of SNF beds available to receive patients discharged from inpatient care.

Resolving the fundamental disconnect between health systems and SNFs

A successful partnership between a health system and a SNF begins with acknowledging that, while both parties are aligned around the goal of providing patients with the highest-quality care, each party has unique interests that will need to be addressed in partnership negotiations.

For health systems, key interests include:

- Offering geographically dispersed SNF beds throughout service areas so patients have options closer to home

- Ensuring the availability of SNF beds for unfunded and medically complex patients

- Maintaining a long-term, trusted relationship with the SNF as a consistently reliable discharge source

- Having insight into the patient’s full continuum of care (a particularly important concern for hospitals and health systems that have entered into risk-based payment structures)

For SNFs, key interests include:

- Maintaining predictable and consistent in-network volume

- Treating patients that can be cared for and discharged on a timely basis

- Maintaining a payer mix that supports a financially sustainable operation

- Establishing clinical alignment with their health system partner (e.g., sharing clinical data, having a dedicated health system liaison and receiving medical and resource support such as medical director rounding or clinical education and training)

In addition, potential partners should acknowledge key challenges to SNF operations, which include:

- Pressures on SNF bed capacity resulting from, for example, staffing challenges and patient preferences for private rooms

- Payment rates that have not kept up with inflationary pressures, further compressing SNF margins

- The need to secure timely managed care authorizations

- Regulatory requirements, clinical complexity and behavioral challenges that can be associated with difficult-to-place patients

- Overly burdensome or time-consuming hospital discharge processes

Combined, these considerations mean that a health system likely will need to contribute financial and other resources to secure a mutually beneficial SNF partnership structure that can accommodate all patients for whom discharge to a SNF is medically necessary. The amount of these contributions should be weighed against other considerations, including improvements to the patient experience and outcomes, the financial impact of improved inpatient discharge processes and increased bed capacity, and the extent of control that the health system will have in the partnership.

Evaluating the options

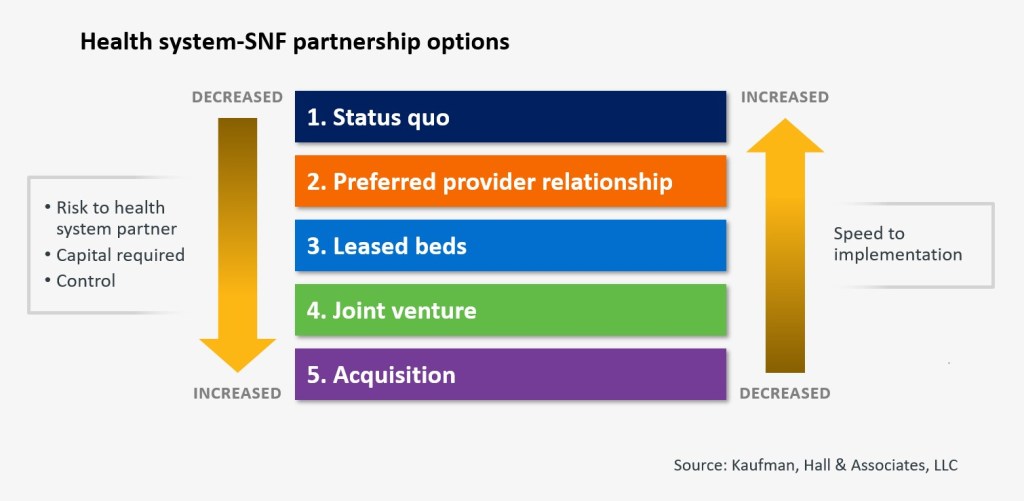

As shown in the exhibit below, options for SNF partnerships range from maintaining the status quo to full acquisition by the health system of one or more SNFs. The exhibit also shows some of the major trade-offs for each of the options. Increased control of the partnership, for example, is offset by increased risk and higher capital requirements, as well as a slower speed to implementation.

Maintaining the status quo should be considered a default option only if none of the other options proves viable. At the other end of the spectrum — acquisition — health systems will have the greatest control. Nonetheless — although acquisition does offer the greatest degree of control — this option should be considered very carefully given the track record other health systems have had in successfully managing SNFs. Any acquisition option should likely be coupled with a management agreement, whereby a dedicated SNF operator manages the day-to-day activities at the SNF.

Between the two ends of the spectrum lie several options that allow for more tailored solutions to balance the partners’ interests and concerns. Each option carries with it pros and cons to weigh against the specific problems the health system is trying to address. Following are three examples.

Preferred provider solution. Under such a solution, a health system contractually aligns with a SNF provider and often designates certain SNFs based on quality or other criteria. This solution varies in its complexity and can take on a variety of forms, ranging from arrangements that are relatively easy to implement and have little to no capital investment or downside risk to more closely aligned arrangements that require financial and clinical/staff investment from the health system. These arrangements can offer flexibility to focus on clinical needs or financial issues depending on the specific patient or provider. They also may allow for a degree of control for the health system partner, as well as dedicated bed capacity and they may address challenges around hard-to-place patients. Arrangements that accomplish these objectives, however, require significant time and investment by a health system. Preferred provider agreements also can be structured more loosely, with fewer health system partner requirements, but these may not yield the same degree of benefit.

Leased-bed solution. With this solution, a health system rents bed capacity. Like the preferred provider solution, this solution involves limited capital and downside risk exposure and also provides dedicated SNF bed capacity. The partners can negotiate agreements for financial or other forms of support around specific payers or patient cohorts. Downsides include limited control over the SNF partner, less-than-full clinical integration, financial investment and the need to find a willing partner with the available beds required for this partnership structure.

Joint venture. This approach offers enhanced governance and control — depending on the ownership interest percentage — and greater clinical integration. Partners also can negotiate agreements around specific payers and patient cohorts. A joint venture will require a more significant capital investment and expose the health system to greater reputational and operational risk. Such a transaction also is more complicated — slowing speed to implementation — and the health system may be viewed by its SNF partner as a backstop if the joint venture encounters financial difficulties.

The realities of any given market may affect the available partnership options, and a hybrid approach to partnership is often appropriate. The number of SNFs that meet certain quality thresholds (e.g., CMS Star Ratings or hospital readmission rates) might limit the range of potential partners, as might the number of SNF beds that are available in the market. The most important factors, however, will be whether the available options will improve the position of the health system over the status quo and enhance the patient experience and outcomes.

Making the business case for a partnership

If a potential partnership option exists, health system management should carefully model the financial impact of the partnership. As noted above, most potential SNF partners will be looking for some sort of support from the health system, ranging from clinical resources to financial subsidies for hard-to-place patients. Health system management should define the resources it can dedicate to the partnership and the costs of doing so.

Against these costs, management should weigh the potential financial benefits to the health system of improving its ALOS through more timely discharge of patients to SNFs. These benefits can range from increased inpatient capacity to more efficient labor utilization to improved ED throughput and volumes.

Identifying and quantifying the full range of benefits against the associated costs of the partnership will help define the parameters for a successful partnership agreement. With a strong business case in hand, health system management can pursue and structure strategic partnership options that will benefit both partners and improve the quality of patient care.

Defining the problem: Solutions for health systems on securing SNF beds

Numerous factors can drive the nature and scope of problems around timely discharge to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). Before considering strategic partnership options with SNFs, health system management should define the specific problems their organization faces by answering several key questions:

- On average, how many patients are medically ready for discharge to a SNF? How many patients are sent to a SNF versus alternative post-acute-care sites?

- Among patients that are discharged to a SNF, what are the drivers of excess inpatient length of stay?

- What types of discharges are causing the most delays? For example, are delays most common for certain diagnoses, co-morbidities, payer sources or at-risk populations?

- What is the status quo? How does the organization secure SNF beds today? What do current internal discharge processes and SNF relationships look like?

[1] Moody’s Investors Service, Not-for-Profit and Public Healthcare – US: 2024 Outlook – Revised to Stable as Financial Recovery Gains Momentum, Nov. 23, 2023.