Why it is necessary to routinely assess healthcare integration initiatives

By their very nature, integrated healthcare relationships need both long-term vision and frequent short-term adjustments.

The strength of healthcare integration comes in part from combining different perspectives, such as those of primary care physicians, specialists, clinical and administrative managers, and IT and finance professionals.

The differences among these perspectives — which involve different business models, maturation patterns and cultures — almost invariably cause business and financial needs to move out of alignment over time (such as the needs of inpatient hospitals diverging from those of physician practices). Leaders at all levels need to make periodic adjustments in relationships and incentives.

A checklist for integration reassessment

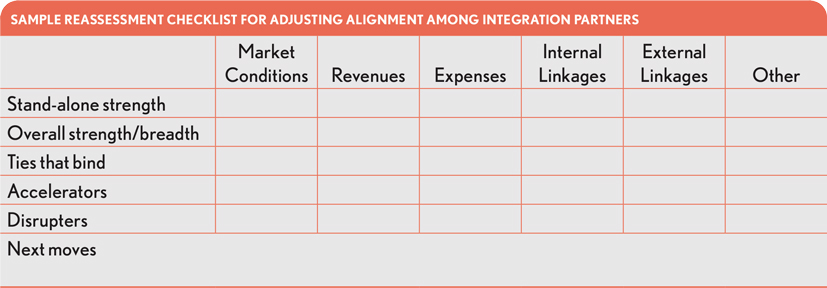

In evaluating the need for adjustments and determining how to make them, executives should consider using a checklist, such as the following.

The reassessment should look at the health system’s relationship with its partners from the following two vantage points.

The stand-alone strength of each partner. Ron Peterson, the former CEO of Johns Hopkins Health System, often referred to himself as a “fiscal surgeon.” He operated from the principle that every element of an integrated health system must stand financially on its own.[1]

Many health systems have adopted Peterson’s perspective. Yet almost every health system has a subsidy for primary care (and often a subsidy for medical education), which is “baked in” before the health system expects any partner to be self-sufficient. Leaders understand that primary care investments have to be matched to the needs of the rest of the integrated system. But after this adjustment for primary care, does each element of the system stand on its own?

Most reassessments begin by looking for weak points, such as:

- Whether each element of the health system is making a positive margin and covering its overhead allocation

- Whether all elements are displaying similar growth patterns, and whether, given changes in market conditions, it might be necessary to re-invest or pare back somewhat

- Whether each element projects a strong market image, with excellent customer service

- Whether there are pockets of concern about burnout or disenchantment

- Whether there are signs of management weakness in any of the elements

- Whether there is a need to rebalance the elements in relation to each other (for example, where primary care is weak while the rest of the system is strong)

The overall strength and breadth of the partnership. The reassessment also should consider whether the overall health system is healthy and positioned well for the future. Key questions usually include the following:

- Is the health system big enough to realize the available economies of scale?

- Has the health system been slow to respond to demographic growth patterns in the market and relate well to the key demographic groups, or could it benefit from a new partner that could fill in the gaps?

- Should the health system consider new forms of integration with payers?

- Is enough attention being given to looking ahead (e.g., to precision medicine and artificial intelligence)?

The ties that bind

During a reassessment, organizations that are loosely integrated (for example, joint ventures between health systems) may contemplate whether they should seek closer forms of integration (such as full mergers with selected reserve governance powers for subsidiaries).

A key consideration is how responsive subsidiary organizations should be to each other. Some might seek to realign incentives and cultures within their systems. Others believe it’s better to be a distinct entity. From what we have seen, most health systems believe closer integration is worth the substantial investment required, and are further integrating IT.

Some leaders are considering re-visioning their integrated system and partnerships as “multi-modal.” They envision a new, bigger relationship for future initiatives, such as precision medicine. Meanwhile, they also envision themselves as local, nimble organizations tailored to meet the needs of their specific customers and market conditions.

Accelerators and disruptors as part of the process

After completing the integration reassessment, health systems should consider accelerators and disruptors and the possible role they might play in this process.

Accelerators. After a reassessment, a health system likely will want to reallocate capital based on the following:

- Opportunities for short-term fixes and targets

- Promising long-term options for investment

- Ways to take a lead in culture and performance at the local level

For example, linking and communicating between the health system and the patient/customer is an area health system leaders often identify for accelerating changes. The bar continues to be raised on tailoring the customer experience based on social determinants of health, mental health, preferred forms of communication and other preferences.

Disrupters. Integrated care is both a disrupter and a disruptee. It is vulnerable to disruption because it takes so long, and it has so many moving parts. It requires putting the right people — with the right training, the right decision support and the right technological and clinical advancements — in the right places. This process takes time, especially in the development of the right internal relationships. Meanwhile, the whole process can be disrupted by outside forces.

A new integration also can cause positive disruption, however. A new strong combination of a health system with well-positioned

medical practices and the right health plan relationship can shift a healthcare market almost overnight. Or a new link to precision medicine can create a long-term competitive advantage.

Next moves

The ideal integrated system is never static. It constantly adds new partners or elements, pares back on or eliminates partners or elements that no longer fit and optimizes and spreads successful innovations. It creates a bulwark against disruption, while exerting a disruptive force on its own.

3 realities defining future integrated healthcare organizations

For many industry analysts, the future for integrated healthcare organizations is seen as encompassing three interconnected realities

- A diversified investment pool for precision medicine, IT and artificial intelligence platform

- A cost-sharing and buying group for anything and everything

- Highly nuanced and responsive yet locally tailored systems of care

Realizing this future may require several actions, including new partnerships and revised governance in the existing partnerships.

Footnotes

[1] For simplicity, we refer to each element of an integrated system here as a partner. In reality, elements are not all the same. For example, among other things, they can be sub-units of a larger organization, legal subsidiaries, joint venture partners or contractors.