HEALTHCARE 2030: LET’S GET PERSONAL

Tailoring care to the patient’s needs presents an opportunity for hospitals and physicians.

By Nick Hut

HFMA Senior Editor

PHOTO BY MARSHALL CLARKE

It was back in the early 2000s when the cardiologist Elizabeth Nabel, then with the National Institutes of Health, described precision medicine as the future of healthcare.

“We’re 20 years later, and I would say we do not practice precision medicine,” said Svati Shah, MD, MHS, associate dean of genomics and the director of the Duke Precision Genomics Collaboratory in Durham, N.C.

A tipping point is in sight, however. Spurred by continuing technological advances and recognition by legacy healthcare stakeholders that the status quo care models need updating, personalized medicine increasingly is gaining traction. (Note: Personalized medicine and precision medicine are used as interchangeable terms in this report, as they often are in healthcare circles generally.)

By 2030, healthcare increasingly will be catered to a patient’s unique physiological, genetic, social and even financial characteristics. Yet work remains to realize that vision.

Structural changes are necessary because the current healthcare system is not designed to support the delivery of personalized medicine. Regulatory and reimbursement structures must adapt to commercialize and lure more capital to cutting-edge diagnostics and treatments.

Although much of the impetus falls on the policy and payment communities, “Health systems really need to embrace this paradigm,” Shah said.

“The fiscal milieu of health systems is getting more and more complicated and more constrained over time,” she said. “But if you have a long-term strategy as a health system, precision health and support in preventing disease will in the long run provide a financial ROI, as well as what’s right for the patient.”

The need for personalized medicine

The goal of personalized medicine is to bring “the right treatment to the right patient at the right time,” Shah said. “As opposed to: I have a patient in my clinic and I’m going to treat them the [same way as] these big clinical trials that looked at 10,000 patients, [and] they represent only a small proportion of the variance of that patient group.”

She added that personalized medicine is geared toward answering the question: “What can we learn about our patients that we don’t get from that single snapshot for 15 minutes every six to 12 months that we get in clinic?”

Clinical guidelines and best practices have tended to be cookie-cutter in nature, Shah said. Such an approach is not often conducive to identifying effective treatments.

Generally speaking, Shah said, physicians “are using a handful of things in single snapshots to figure out what to do with that patient as opposed to using what’s really granularly going on with them in their bodies as well as what’s happening to them in their lives and incorporating all that information to figure out the best treatment for them.”

Taking stock of advances

A driving force in personalized medicine is technology that has made performing blood analysis far more exact. Clinicians and scientists can quickly and efficiently analyze the 3 billion nucleotides in a person’s genome, zeroing in on the 0.4% that vary from one individual to the next.

A prime example is seen in the breakthrough cholesterol-lowering class of drugs known as PCSK9 inhibitors. The genesis of the treatment was an inquiry about why certain people have very low cholesterol, and how that trait could be mimicked in a drug. Genetic mapping revealed the source was a mutation that caused a recently discovered gene called PCSK9 to stop functioning normally.

One drug undergoing trials would require only a single dose over a patient’s lifetime to lower cholesterol by inhibiting the PCSK9 gene. Shah described the treatment as “a vaccine for heart disease.”

Personalized medicine also improves scenarios in which a diagnosis is elusive. Shah said applying genetic-sequencing technologies — “really looking at the individual human being, and not just how they fit into large populations” — provides a solution in at least 30% of cases that previously went unsolved.

At the same time, digital health devices present a mechanism for funneling vastly more clinical and physiological data about an individual to a provider. The ability to store and analyze terabytes of reference data, Shah said, means technology can be brought to bear on clinical questions that require huge quantities of data to parse.

AI is helping providers process and make practical use of data, and one vital application is interpretation of imagery.

Shah, a cardiologist, estimated she overlooks “probably 95% of the data that’s actually in those images because I’m using a human eye and not a computer eye.”

A financial blueprint

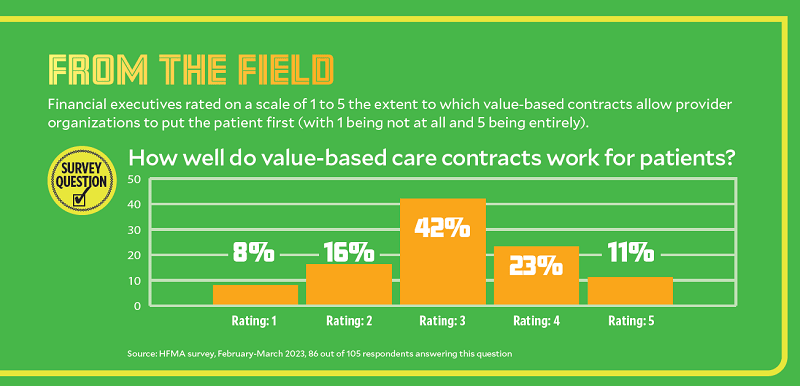

Value-based payment (VBP) promises to give stakeholders a greater incentive to apply personalized approaches to healthcare assuming it continues to gain a foothold and ultimately is adopted.

Despite the potential for significant upfront costs, Shah is optimistic about the financial return from a personalized approach.

“You can actually have a short-term financial ROI from investing in genomic medicine programs, where you’re using genetics and genomics to identify people who are at risk of disease and then implementing systems of care to prevent those diseases,” she said.

As a performance driver in VBP models, personalized medicine encompasses more than a person’s clinical characteristics. At Corewell Health in Grand Rapids, Michigan, researchers sought to predict which segment of discharges most needed additional resources. They developed a model that helped them identify the relevant 3% to 5% of patients, and published the results in an issue of NEJM Catalyst, in an article called “Reducing readmission risk through whole-person design.”

— Tricia Baird, vice president of care coordination, Corewell Health

Embedded in the health system’s electronic health record (EHR), the model considers more than 60 factors, including diagnoses, medications and number of past admissions. The Corewell researchers added a point score that reflects whether a patient has a strong primary care relationship. That additional input raised the model’s predictive capability from 0.71 to 0.9 (meaning out of every 10 patients who were placed in the high-risk group, nine were categorized correctly).

Said Tricia Baird, MD, MBA, vice president of care coordination with Corewell Health: “Before we even got the math back, we could feel that we were headed in the right direction because teams started calling me saying, ‘How did my [colleague] get that in their screens? I want that in my screens. How can I see that information?’ And people were just organically adopting the score.”

A key feature of the model is the ability for care managers to easily see the algorithmic components that stand out in an individual case.

“They don’t have to make the patient repeat their whole life story,” Baird said.

Incorporating social factors

Baird distinguishes between health equality, which means providing the same type and level of support to everyone, and health equity, which refers to providing tailored support to all patients.

In Corewell Health’s predictive model, “It was very important to us to overlap clinical health, behavioral health and those social determinants of health,” Baird said.

She noted the research team had equal numbers of nurse care managers and masters-prepared social workers, with community health workers eventually joining to help with the deep dive into social determinants.

“This intervention is designed to be started at the bedside or started as the patient’s discharging, and finished within a month,” Baird said. “We want our patient moving toward an ongoing medical home, a relationship that will carry them. This [research] team is meant to help solve some of those first two, three, four weeks of problems so that patients will trust themselves and trust us a health system.”

As stakeholders consider ways to address holistic health issues, the need to account for the distinct circumstances of patients’ lives becomes more urgent.

“Part of why we were so good at predicting this small group of patients that was highly likely to come back was because it wasn’t one thing. It was an overlap of all these things,” Baird said. “That’s where that power of finding patients who didn’t have an outside-in-the-world [healthcare] relationship [came in]. Some things were going to crop up, and if they didn’t know who to call or the person they called couldn’t take care of the entirety of their question, they would start to slip in their health until they ended up back in the hospital.”

Customizing the revenue cycle

For patients to feel well-served by the healthcare system, the financial experience also must become more personalized.

— Candi Powers, chief revenue officer, University of South Alabama Health

Although the concept of a digital front door can enhance convenience and access, patients are looking for more, said Candi Powers, MBA, CRCR, chief revenue officer for University of South Alabama Health (USA Health) in Mobile.

“What our patients are looking for is the digital wraparound porch,” she said. “They want it from the front to the back. It’s not just about checking in.”

The back end of the patient experience stands to be a true differentiator in customer service. Initiatives should extend well beyond patient-friendly billing statements, Powers said.

“It needs to go to our patients’ individualized, customized experience with us,” she said. “What caregivers did they see in that space? And how do we get all of that in one location so that they can access the resources they need?”

Powers added that some organizations “absolutely do not want to crack open a Pandora’s box to provide text messaging and pay-now options on patients’ cellphones.

But she said there are benefits to being able to say to patients, “You were just in the ER five days ago. You have Blue Cross Blue Shield. They’ve adjudicated your claim. This is how much you’re going to owe. Would you like to pay it now?”

“Go through that simple verification, and then let patients pay where they are,” Powers said.

With disrupters slicing into the market share of legacy providers, at least for some healthcare services, it’s easy to envision the availability of a personalized revenue cycle experience as a swing factor.

“Those who do it well will have a distinct advantage in the market,” Powers said. “I’m going to go where it’s easy to do it, as a patient.”

Finding the right resources

As is the case in clinical operations, there’s an opportunity for personalization in the revenue cycle to improve outcomes.

“We can manage the care better administratively, making sure they’re getting to their follow-up appointments, [maintaining] their medication adherence,” Powers said. “The revenue cycle has stepped into some of those administrative functions in recent years.”

She added, “There are pieces we haven’t touched yet around social determinants of health and getting people in touch with the resources that they need, and really engaging with patients to meet them where they are.”

For example, the revenue cycle can support a form of personalized outreach in instances when a patient accesses a health system — such as through the emergency department — and doesn’t list a primary care physician. Those patients can be placed in a queue for the health system’s call-center preservice function to proactively make connections with primary care.

Such efforts are likely to be more manageable in the revenue cycle than by clinical navigators.

“We have the resources to do it,” Powers said. “You just have to tweak them a little bit.”

That may mean phasing out manual administrative tasks.

“We hold a lot of [claim-related information] just to check it and make sure that it’s correct before it goes out the door,” Powers said. “All of that is important, but none of it requires a human anymore. I’ll be on a mission over the next three to five years to really free up that knowledge base to do more customization at the patient level — getting folks aligned with the right resources that they need.”

Potential solutions still untapped

One obstacle to the widespread implementation of personalized care is the lack of synchronicity between the healthcare system and manufacturers of devices such as Fitbits and Apple Watches.

“Health systems have to be at the center of these conversations to really push these companies, to say, ‘You need to work with [healthcare stakeholders],’” Shah said.

EHR vendors also have a crucial role.

“If I take all your raw Apple Watch data and stick it in your patient chart, I don’t have time in-clinic to look through those data,” Shah said. “We need structured ways to take those data and bring it to clinicians to say, ‘I know you only have 10 minutes to take care of this patient. I just wanted to flag one thing for you. Their heart rates have been getting to 200 when they’re exercising, based on their Apple Watch data.’ And [it provides] a little flag to say, ‘Hey, maybe you should address this.’”

Technology barriers also affect revenue cycle efforts to customize the patient experience. For example, interoperability has not reached a stage at which providers can efficiently assist patients based on the various permutations of their insurance coverage (or lack of coverage).

“We should not have to, [for] an individual case, be obtaining the financial and benefit information for our patients,” Powers said. “We should be able to interface our systems [with insurers], and enough information should be able to flow to where we can do that in a much more efficient, automated, streamlined way — where we get all the individual patients and their individual details, but in an electronic format that is easily digestible into our systems.”

What lies ahead

Revenue cycle departments, Powers said, should plan to invest in technology that presents “the simplest path from A to B for the patient from the standpoint of shopping for the service, scheduling the service, checking in for the service, being able to interact with their medical record.”

And then, USA Health incorporates the myriad financial expectations and is able to monitor if the patient truly is satisfied.

In a clinical context, the ability to use data to create customized care plans presents intriguing options.

“You can think of lots of complicated disease journeys in specialty care, or just lots of places where there are healthcare ‘tribes’ that would benefit [patients],” Baird said. The idea is to identify patients “early in those long, complicated journeys and suggest that there might be a tribe or a group that would help them get the answers, get the support and stay with the treatment. To me, that broad matching of subgroups or subtopics has the most short-term excitement.”

The government may need to play a role in motivating disparate groups of stakeholders to work together on technology implementation and in striking “that delicate balance of making sure that the FDA isn’t creating onerous processes for being able to bring these things to patients, but also making sure there’s data to support actually bringing it to a patient,” Shah said.

As futuristic as personalized healthcare can seem, big strides are within reach.

“It’s not like we need to invent huge new tools,” Shah said. “We have to work together to use those [existing] core pieces, so we can not only take the discoveries that we already have and make them applicable to our patients, but also it builds the infrastructure for new stuff that comes down the line — so we’re not waiting 30 years to take something new and actually apply it to our patients.”

Personalized vs. populations

Based on terminology, personalized medicine would seem to conflict with another prominent trend in healthcare: population health management.

— Svati Shah Associate dean of genomics, director Duke Precision Genomics Collaboratory

And yet, “You can’t have one without the other,” said Svati Shah, MD, MHS, associate dean of genomics and the director of the Duke Precision Genomics Collaboratory.

In population health management, researchers strive to understand relationships such as the connection between proximity to a highway and risk of heart attack.

“If you don’t do population health, you would never have known [about] that,” Shah said. “But then the way you take that information to the person in front of you — you might be able to say, ‘Look, I know you have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease because you live next to a highway, so here are some strategies for mitigating that risk.’ We’re understanding risk across populations, but then we’re using that for the individual in front of us.”

Population health considerations also should trigger questions about equity and access, “making sure we’re being inclusive across communities,” Shah said.

For example, “The more rural you are, the less your access to medical care,” she said. “That’s part of how we think about population health and community health broadly, but it very much fits with precision health. Precision health isn’t just around a certain demographic or people who have access to high-level care.”

— Nick Hut

Personalization as a tool to build trust

Personalized care offers a route to addressing the lack of trust that patients increasingly seem to feel toward some aspects of the healthcare system.

— James L. Heffernan, retired senior vice president of finance and treasurer, Massachusetts General Physicians Organization

That idea arose in discussions at HFMA’s 2023 Thought Leadership Retreat, which took place Sept. 28-29 in Washington, D.C., and focused on how stakeholders can restore trust in healthcare.

One leader who attended the retreat linked personalization to the value push in healthcare.

“The way to really make this work is to get much more personal about how we deal with care,” said James L. Heffernan, FHFMA, MBA, who recently retired as senior vice president of finance and treasurer of Massachusetts General Physicians Organization. “Why can’t we take tools [like] AI, the expanded access to data, and begin to build a real value-based system that’s specific to the individual? One of the reasons people get lost in this is we’re spreading the resources we have over everybody equally, and not targeting the individual’s needs.

“We don’t need a new structure because nurses have been dealing with individuals for years; doctors have been dealing with individuals for years. All we have to do is give them real-time access to data and build out the tools so they can use their talents.”

After the event in an interview, Heffernan said that advanced personalization tools increasingly are becoming available to clinicians. These include resources that can predict delirium for patients during hospitalization and post-discharge; determine the best treatment course (e.g., surgery, medicine, a nonsurgical procedure or watchful waiting) for an individual patient seeing a particular type of specialist; or pinpoint specific cancer treatments, such as transplant immunotherapy or CAR T-cell therapy.

“It’s actually pretty exciting,” he said.

Issues of equity must not be overlooked in the effort to make care more personalized, said Robyn Begley, CEO of the American Organization for Nursing Leadership.

“Personalized medicine is absolutely the future, but it’s got to be for all, and we have to figure out how we’re going to make that happen,” she said during the retreat.