Maintaining the equilibrium of the physician enterprise amid rapid change is a matter of balance

Mattew Bates

David Masters

The human body is equipped with a heart, blood and blood vessels that work together to provide adequate tissue perfusion. The proper functioning of this system, known as the “perfusion triangle,” is essential to sustaining human life. If the perfusion triangle becomes materially imbalanced, the body will go into shock and may even die.

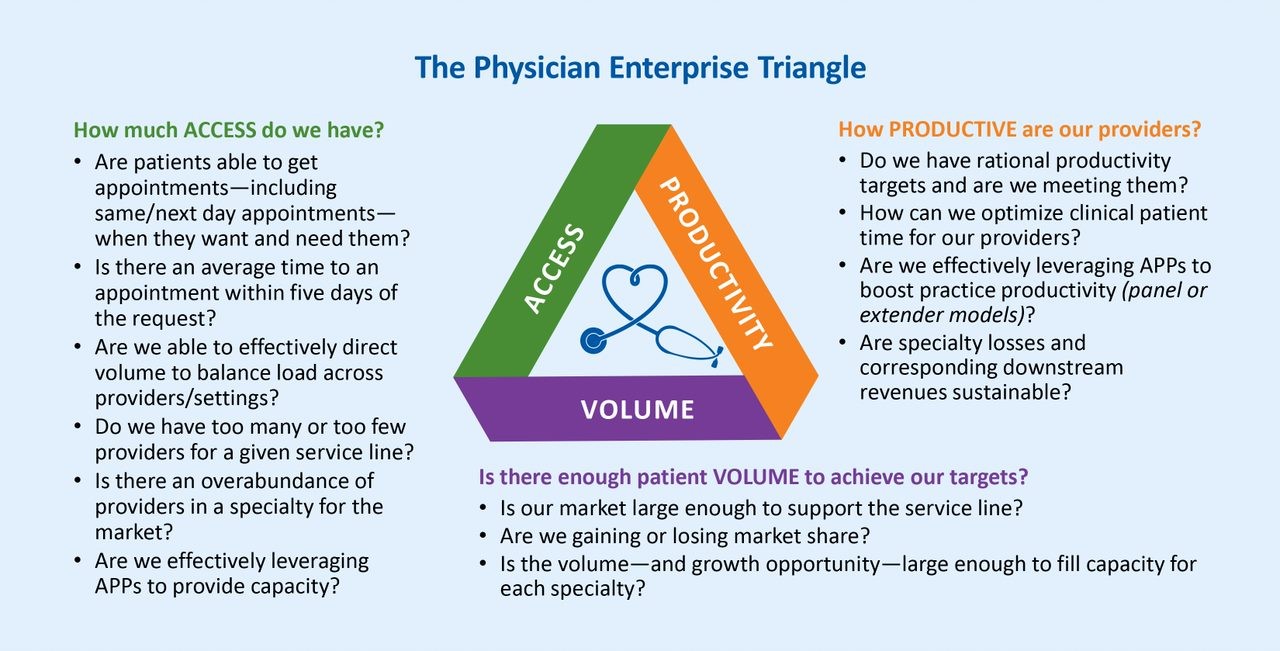

By analogy, a hospital or health system must balance three dimensions that make up what we call “the physician enterprise triangle”:

- Its clinicians’ productivity

- Its capacity to provide access to care to patients when they need it

- The volume of existing and potential patients in the markets it serves

When organizations make changes in any one dimension, they inevitably impact the other two dimensions — and can potentially disrupt the equilibrium of the entire system.

Physician enterprise leaders charged with maintaining this delicate balance are also confronting a rapidly evolving industry. Outpatient care accounted for 49% of gross revenue for community hospitals in 2018, up from 30% in 1995, according to the American Hospital Association (AHA) — a trend that has further accelerated since the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The AHA notes that the total number of outpatient visits to community hospitals grew by 85% over that same time frame — to 766.4 million visits in 2018.

Value-based, coordinated care models are also on the rise. The AHA also estimates that nearly 1,800 hospitals and health systems participated in an accountable care organization in 2018 — up from roughly 200 in 2011.

The Physician Enterprise Triangle

Source: Kaufman, Hall & Associates, LLC, 2021

Balancing the triangle dimensions

To keep the organization in balance, physician enterprise leaders must be able to simultaneously measure and track shifts in productivity, access and volume. The insights derived from these efforts and the metrics are critical to understanding how addressing a problem in one dimension can impact the entire physician enterprise, thereby making it possible to avoid the pitfalls that arise when an effort to fix a problem in one area causes problems elsewhere.

Consider the three sets of metrics that work together to provide the necessary insights.

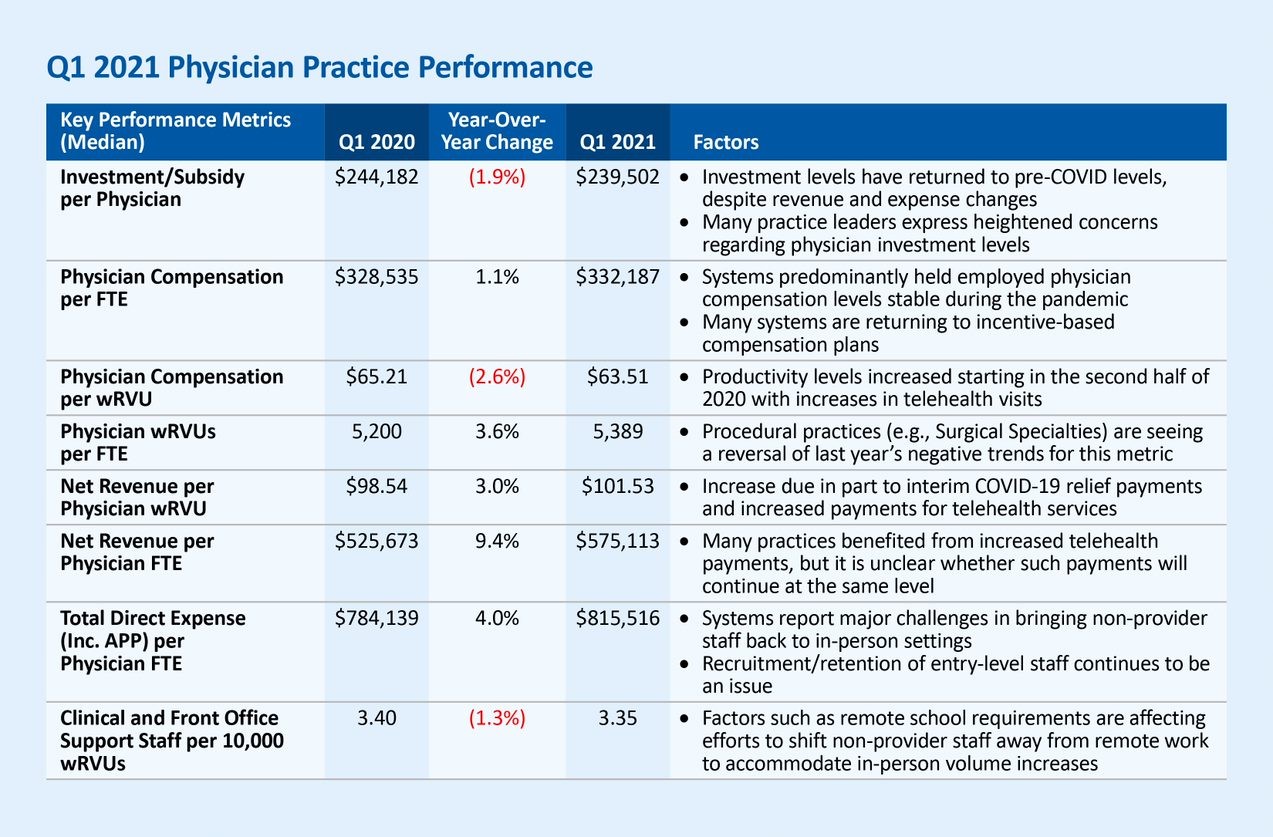

Productivity metrics allow organizations to identify reasonable targets for the productivity of physicians, advanced practice providers and other clinicians — and develop strategies for meeting them. Organizations should also be able to determine whether the losses sustained by specialties are sustainable in light of the downstream revenues they generate. Recent trends suggest that investment levels are stabilizing to pre-COVID levels. The median investment/subsidy per physician FTE in Q1 2021 was down 16.3% from a high of $286,089 in Q2 2020, according to Kaufman Hall’s June 2021 Physician Flash Report. Key metrics for assessing productivity include:

- Benchmarks for work relative-value units (wRVUs), or the relative time it takes to complete a specific procedure, for all locations of the practice

- Productivity by physician/advanced practice provider team or specialty

- Controllable investment per physician by specialty

Access typically helps determine whether there are enough providers to manage ongoing patient demand for care. At the beginning of the care experience, organizations must be able to efficiently schedule care for incoming patients. Otherwise, patients with relatively urgent care needs may leave the system if they cannot be seen within a short time frame. And even for primary care providers fielding less acute calls, ensuring patients can be seen in the office or in an urgent care center is important.

To meet patient access needs, providers need to track and adjust how many physicians they employ or affiliate with relative to a specific service line as well as the relative number of those physicians in their market.

Key metrics include:

- Percentage of patients requesting a same/next day appointment that are accommodated

- Percentage of patients seen by system physicians and referred for additional diagnosis/treatment who are seen

- Percentage of patients requesting visits who are seen within two weeks

- Percentage of patients calling for appointments versus patients actually seen

- Percentage of new patients that return for a second visit or service

The patient volume available within the organization’s market will ultimately determine whether the organization can meet its productivity goals within its available provider capacity. Trends in volumes should provide insight into three key areas of market dynamics:

- Activities of other providers in the market

- Whether market share is increasing or decreasing

- Whether there is potential excess patient volume that can provide opportunities for expansion

In particular, shortages of certain specialties are a recurring problem for hospitals and health systems. The American Association of Medical Colleges projects a shortage of primary care physicians of between 21,400 and 55,200 physicians by 2033, and a shortage across the non-primary care specialties of between 33,700 and 86,700 physicians.

Key patient-volume metrics include:

- Patient population in market area by specialty/service line

- Market service area by specialty/service line

- Market share by specialty/service line

The Kaufman Hall Physician Flash Report tracks key metrics shedding light on physician enterprise trends each quarter. A summary of the June 2021 report is provided below.

Q1 2021 physician practice performance

Source: Kaufman, Hall & Associates, LLC, 2021

Achieving equilibrium

When physician leaders identify a problem in a specific dimension, their understanding of the other two areas should inform decision-making. While volume within a given market is often beyond the control of an organization, the system can influence two sides of the triangle:

- Physician productivity

- Access to care via available capacity (i.e., the number of physicians that are employed or otherwise affiliated)

The following are pitfalls that can disrupt balance.

Lack of data. In some instances, organizations focus their efforts on ensuring they can maintain physician capacity for patient demand — without paying enough attention to related trends, including the number of hours physicians work, patient no-show rates and the degree to which advanced-practice providers (APPs) support physician productivity.

Inconvenient scheduling. Scheduling processes that become overly complex or restrictive can reduce physician capacity — and in turn hamper physicians’ ability to provide access to care and meet productivity targets. If scheduling difficulties lead to longer wait times, the probability that a patient will be a no-show also increases. According to the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), physician practices in the U.S. reduced times for the third-next-available appointment — their benchmark measurement for appointment availability — by one to two days from 2018 to 2019, while wait times for new patients increased by two to three days over the same period.

Physician productivity. Physicians (and APPs) are being overburdened with administrative tasks, which preclude them from clinical time to take care of patients.

Overstaffing. If a system accumulates too much capacity, it can overwhelm the existing volume in the market. Physician practices must be able to track and determine how many providers they need based on existing volume — as opposed to making decisions based on the potential for volume. Another challenge: A lack of publicly reported data regarding ambulatory care can make it harder for organizations to gauge potential available volume.

Building demand without sufficient staffing. Conversely, if there is ample volume to support productivity, organizations will need to carefully make decisions about marketing existing services to avoid understaffing as volume grows.

The role of the physician enterprise leader

The job of a physician enterprise leader is to balance productivity, volume and access across the full continuum of care. As healthcare continues to shift its front door from the emergency department to the physician’s office, the importance of crafting an integrated approach will only increase. For instance, a radiology center might have responsibilities for both inpatient and outpatient care, requiring carefully balanced scheduling.

All too often, department heads, finance leaders and other managers will focus on solving problems strictly within their scope, which can lead to problems elsewhere in the physician enterprise. Ultimately, organizations must be able to empower physician enterprise leaders to manage productivity, access and volume simultaneously — and maintain the balance needed to thrive in the nation’s healthcare delivery system as it continues its rapid evolution in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.