For healthcare analytics, systems and culture breed success

Research conducted by HFMA and sponsored by EPSi shows that healthcare organizations are still grappling with technological and cultural issues as they attempt to implement effective analytics programs.

- More than 80% of healthcare finance leaders expect their investment in analytics programs to increase over the next two years, according to a new HFMA survey.

- Technological and cultural issues are two of the leading impediments to realizing a return on analytics.

- One way to overcome those obstacles is to ensure the analytics program is molded to the needs of the end-user.

Although healthcare organizations increasingly recognize the importance of incorporating analytics in their day-to-day operations, executing that strategy remains a thorny task.

Among the most significant issues are the challenges of utilizing outdated, siloed systems and of instilling an organizational culture in which the value of using analytics is widely understood, said healthcare leaders who responded to the first part of a three-phase survey conducted by HFMA and sponsored by EPSi.

“A primary driver for EPSi to lead this research is what we have been hearing from our clients about the importance and challenges of setting a strategy and then executing on that with better analytics practices and tools,” said John Gragg, COO of EPSi. “We had hypotheses about broader industry priorities and shortfalls, and the research confirmed many of them.”

“It can be difficult for organizations to recognize the full impact of culture on the success of various tools in the organization’s toolbox, including analytics,” said Chuck Alsdurf, director of healthcare finance policy, operational initiatives, for HFMA. “It’s crucial to weave respect for the power of data into organizational culture.”

As the push to realize the potential of analytics gains steam, healthcare organizations are seeking newer, more innovative systems and best practices for infusing the type of culture that promotes success.

The industry outlook on analytics

Conducted in July and August 2019, the survey included responses from 327 executives, managers, and directors at hospitals, integrated delivery networks (IDNs), physician practices and other ambulatory sites. In response to one survey question, analytics was defined most frequently (30% of respondents) as “data and metrics used to make decisions.”

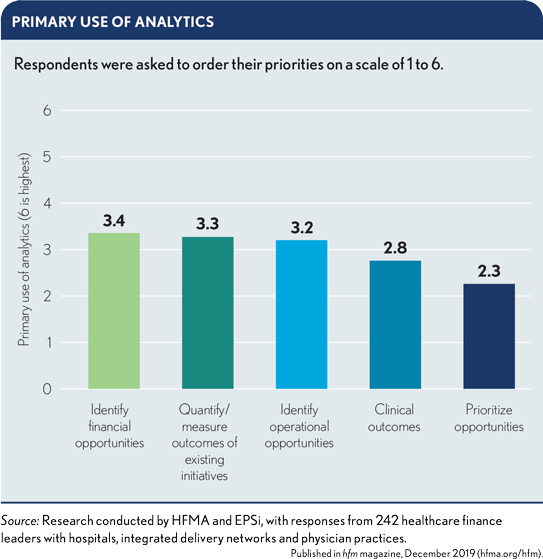

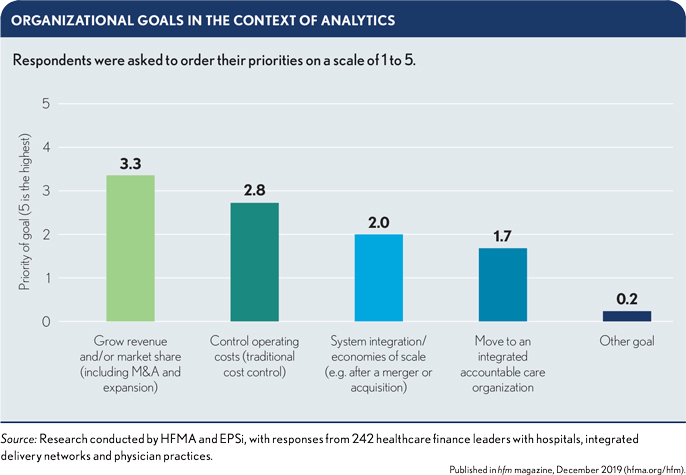

Leading areas of analytics application, based on survey responses, are identifying financial opportunities, quantifying outcomes of existing initiatives and identifying operational opportunities (see the frst exhibit below). These activities support organizational goals such as growing revenue and/or market share (e.g., through merger-and-acquisition activity or expansion) and controlling operating costs (see the second exhibit below).

Survey responses indicated organizations are making progress in areas of focus. Improvement in operational effectiveness stemming from the use of analytics was deemed “somewhat favorable” or “very favorable” by 84% of respondents. For financial sustainability, the favorable response rate was 80%. No other area evaluated in the survey (enterprise risk, growth, real-time information and quality/safety) did better than 69%.

Part of the challenge of realizing a return on analytics can be tied to metrics. Specifically, 29% of respondents have no measures in place and 15% can measure value only on specific projects or performance reports. Additionally, over half of respondents stated strategy and analytics are only somewhat aligned or not aligned at all.

And yet despite limited understanding of analytical return and poor alignment in spend with system-level strategies, organizations appear poised to continue to make greater investments in analytics over the next two years, with 54% of respondents saying their organization’s investment will “increase somewhat” and 27% saying it will “increase significantly.”

How cultural factors affect the outlook for analytics

Of 221 responses to a question about organizational culture concerning analytics, 41% described the culture at their organization as “mainstream,” while 33% said it was “progressive.” Fewer respondents perceived their organization as being at either extreme, with 13% selecting “laggard” and 12% choosing “innovator.”

Based on the survey responses, acute care hospitals trail IDNs and physician practices in terms of analytics-focused innovation. Among respondents from acute care hospitals, 37% described their organization as “progressive” or “innovative” with respect to analytics, compared with 49% at IDNs and 55% at physician practices.

“It doesn’t happen overnight,” said Philip Lieffers, director of finance for Northern Physicians Organization, a Michigan-based group of independent physicians. “You need to find leaders that will take that mantle and really push it forward. We’re a nimble, small organization, and we have some really great folks who have worked with data in lots of different organizations and understand how it impacts outcomes.”

Inertia tends to set in at organizations across industries, said Bowen Lancaster, a facility CEO with Compass Health, a Louisiana-based provider of psychiatric health services. When that happens, incorporating analytics into the fabric of operations requires overcoming the human tendency to resist change.

“With pretty much everything in the industry nowadays,” Lancaster said, “you still have that mentality: ‘That’s the way we’ve always done it.’ They want to stick with that process even though maybe it hasn’t been getting the best results.

“The best way to handle cultural factors is to pretty much implement an entire cultural change at the facility, and that starts from the top down. You work with each member of your management staff. You make sure they understand the program and understand what they’re looking at, how to use it. Nothing puts up that wall faster than not truly understanding the product.”

Roadblocks to analytics implementation

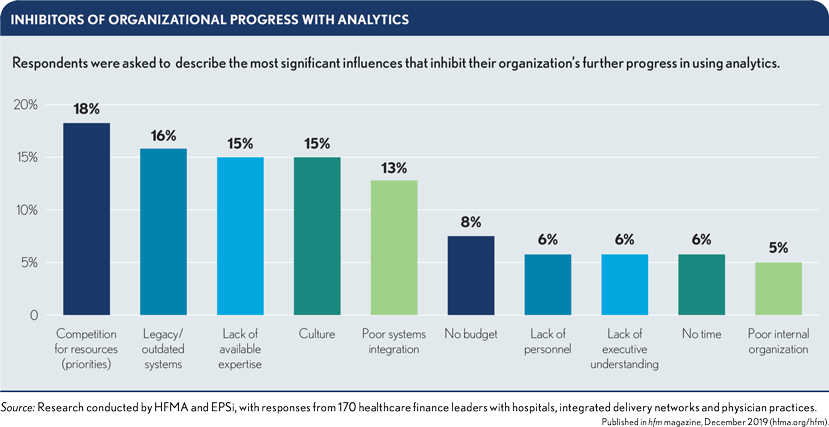

Based on the survey, inhibitors of analytical progress were largely associated with two underlying challenges: cultural issues and suboptimal systems.

Nearly 30% of respondents identified “legacy/outdated systems” and “poor systems integration” as a core inhibitor to analytic success. “Outdated systems and poor integration can be directly tied to operational cost,” EPSi’s Gragg said. “They represent the avoidable cost that organizations carry from the point of occurrence to the point of identification. The longer a system takes to identify poor patterns of behavior after occurrence, the greater the financial exposure and the harder it becomes to break the bad patterns.”

Many industry leaders are becoming acutely aware of this challenge in data acquisition and analytics dissemination, as are the operational and clinical stakeholders who use the analytics. Jon Vitiello, senior vice president of financial operations and analytics at Mercy Health in Chesterfield, Missouri, is experiencing this trend. “We’re getting more efficient in our operations in our hospitals and clinics,” he said, “and we’re having those department directors and managers ask us, ‘How am I doing? I can’t wait until the end of the month or the end of the quarter. I’d like to know how I did yesterday, today.’”

Culture as a stand-alone inhibitor polled at 15% for respondents, outpaced by competition for resources (18%) and legacy/outdated systems (16%). But when incorporating other inhibitors that reflect poor culture — lack of executive understanding (6%), poor internal organization (5%), poor leadership (2%) and poor data governance (2%) — culture-based challenges comprise 30% of the issues precluding success.

“Poor culture also can be tied directly to operational cost,” Gragg said. “It represents the avoidable cost that organizations carry from the point of variance identification to the point of remediation. And this number can be significant.”

Yet cultural issues may be an underlying issue that goes unrecognized, said Kim Carter, director of coding, PB compliance and health information management with Legacy Health in Portland, Oregon.

“Is the culture telling a clinic manager to be out solving problems and available for her staff throughout the day, or is it requiring her to also be looking at the data to ensure that they’re meeting their targets for the day? It’s about getting a little bit more data-focused as we go along. That’s a cultural shift,” Carter said.

First steps to overcoming obstacles

Implementing an analytics program in healthcare organizations requires a few key insights, said Pamela Gallagher, founder and CEO of Gallaghers Resulting, LLC, a healthcare performance solutions firm. “You have to have an understanding of what analytics is,” she said. “You have to validate it, and then you have to have a willingness to work with each other.

“Especially in finance, we have a tendency to love numbers and show them, but they have to be meaningful. What does it mean to users? I delivered finances one time with just one number — the number of paychecks they had lost. They got the message really quickly. It has to be applicable.”

Other stakeholders agreed that analytics should be molded around the needs of the end-user and that collaboration is vital.

“Depending on where you are on that continuum of using data in your practice, there’s maybe just a little bit more education, a little bit more talking through how that works,” Lieffers said.

“For us, it was about putting that data in front of our physician leadership,” he added, “talking through how it impacts their actual processes, showing them over time that the work they are doing in their offices with their patients is actually impacting those metrics. I think for many of them it’s intuitive, but until you see it on a day-to-day basis, you may not embrace it fully.”

Cara Morris, director of budget and financial forecasting at UC San Diego Health, echoed the importance of giving context to the data. “I make sure that every analyst understands the clinical and operational stories behind the data before we publish any results,” she said. “If we expect our stakeholders to have a certain level of financial literacy, then we must also hold ourselves to having a certain level of healthcare operations literacy.”

Looking at future research initiatives

Subsequent research by HFMA and EPSi, to be published in 2020, will further delve into the reasons behind underlying issues in analytics implementation and what providers can do to achieve a better return on analytics.

Part of the solution entails reducing the time between poor performance and remediation by providing better data, faster.

“We cannot continue to provide our end-user stakeholders only with studies of retroactive data of the past and hope that they can use the data to solve the problems of tomorrow,” Morris said. “By providing more real-time data to our operators, we can reduce the time needed to recognize poor performance patterns and reduce the time to remediate these deviations. The closer to real-time the analytics, the greater the engagement and use of the data by front-end care delivery.”

For Morris and her team, the journey to real-time analytics requires taking time to build trust in data and rapport with people. Getting an organization acclimated to using analytics “doesn’t just happen overnight,” Morris said. “Without visionary leaders, incredible operators and strong change management teams to develop the tools and guide the rollout, transformation wouldn’t be possible.

“It needs to be a high priority for leadership, and it needs to be supported by software that is built for the future and able to provide more timely data that is actionable. Each organization’s journey to real-time analytics will be different, but to have near-term success, one commonality is the need to start taking action now.”