Reducing clinical variation to drive success in value-based care (part 2)

Last month, we examined the issue of clinical variation reduction in terms of the stakes for value-based care. We also discussed two vital strategies for reducing clinical variation: physician engagement and implementation of risk-based analytics.

Below, we describe two more key aspects of initiatives to reduce clinical variation.

Deployment of physician scorecards

Physicians, like most people, will not change their behavior unless desired changes are being measured, reported and monitored by leadership and appropriate governance committees.

Well-designed and communicated physician scorecards and operational dashboards do more than demonstrate what is expected to change — they also emphasize the importance of the change from the perspective of clinical and executive leadership. Physician scorecards also foster peer comparisons that promote transparency and friendly competition, and the competition accounts for much of the improvement typically seen in the first few months.

Effective scorecards and dashboards show individual metrics and overall results by physician, service line and patient population. Upon introduction of the scorecards, a worthwhile approach initially is to blind individual physician names.

Scorecards should have no more than eight to 10 metrics, tailored to the desired changes for each specialty or physician group or to improvements in a given patient population. Effective physician scorecard and operational dashboard metrics may include:

- Average cost per case

- Per member per month spend

- Various HEDIS and AHRQ quality measures

- Hospital-acquired conditions

- Payer contract measures for value-based care

- Excess days per discharge

- Emergency department utilization

- Readmission rates

- 24- to 48-hour gaps in orders

- Numbers of unrelated procedures

- Clinical documentation improvement query response times

- Case mix index

- Denial rates

- Mortality rates

When scorecards consist of objective and transparent metrics, they are quickly viewed as valuable assessments of performance. Impacted physicians should be given input into the metrics selected, with appropriate departmental and medical-executive approval.

A key benefit of scorecards is the insight they provide into the root cause of a metric’s poor performance against benchmarks or peer results. For example, if one surgeon’s average cost per case is higher than expected, it is helpful to drill down into the components of cost.

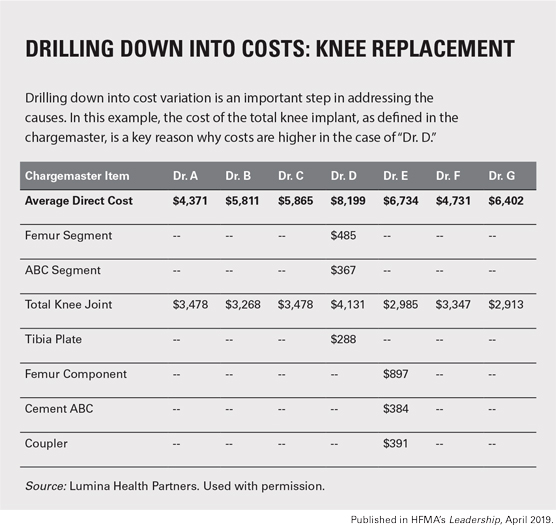

In the example drill-down analysis shown below, the cost of the total knee joint implant by surgeon is shown, as defined in the chargemaster. Providing this type of detailed analysis is effective at identifying and addressing root causes of clinical variation.

Physicians and multidisciplinary improvement teams should be provided with updated scorecards on at least a monthly basis, allowing them to track progress, see measurable reductions in variation and push for further change.

Implementation of evidence-based best practices

Physician scorecards and dashboards — along with utilization of risk-adjusted analytics, as described in Part 1 of this article series — establish opportunities to institute best practices. Multidisciplinary teams composed of key physicians and other caregivers and clinicians, as well as representatives from pharmacy, therapy and other areas as needed, should then be formed to research, develop and implement new protocols.

The focus can easily extend beyond the acute-care hospital to post-acute and ambulatory environments. The Medicare Shared Savings Program’s skilled nursing facility three-day waiver, for example, is an opportunity for the team to create partnerships that emphasize care transformation for a specific patient population.

Ambulatory teams should design protocols like the highly adopted best practice to avoid imaging and begin early physical therapy in patients with mechanical low back pain. Other common conditions seen in the office setting also can be addressed by instituting evidence-based care pathways.

These multidisciplinary teams should monitor financial and quality metrics to ensure improvement targets are met. Newly implemented evidence-based protocols should be reviewed and updated annually to reflect any changes in best practices.

Typically, an existing medical staff governance committee, such as the quality committee, is responsible for overseeing development, approval and maintenance of clinical protocols and order sets. With that approach, physicians are more likely to trust the evidence for the practice — and medical staff compliance is more likely to increase.