The all-volunteer governance model that dominates not-for-profit health systems and hospitals is losing adherents as the role of board director becomes more complex and demanding. At least eight of the largest not-for-profit health systems in the country pay their directors, and experts say additional systems are likely to follow suit or already have.

Jamie Orlikoff, president of Orlikoff & Associates Inc., a consulting firm specializing in healthcare governance, said he has learned in recent months that about a half dozen of his clients have started compensating their board members. Likewise, he is compensated for his work as the board chair of a health system.

Orlikoff sees this compensation trend as one of many signs that the traditional voluntary model of governance may be insufficient for health systems today.

“We need folks who can devote the time, who have the level of understanding, who understand systems, who understand healthcare, who can help guide these organizations through unprecedented times,” Orlikoff said.

May be taking hold

National surveys conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic suggested that between 11% and 14% of health systems compensated their board members, he said. It’s a rate that had remained fairly steady for years, although there are signs that it’s picking up.

“There’s a lot of interest in this,” said Bill Dixon, managing director at Pearl Meyer, an executive-compensation consulting firm. Dixon is working with two systems that are evaluating board compensation this year.

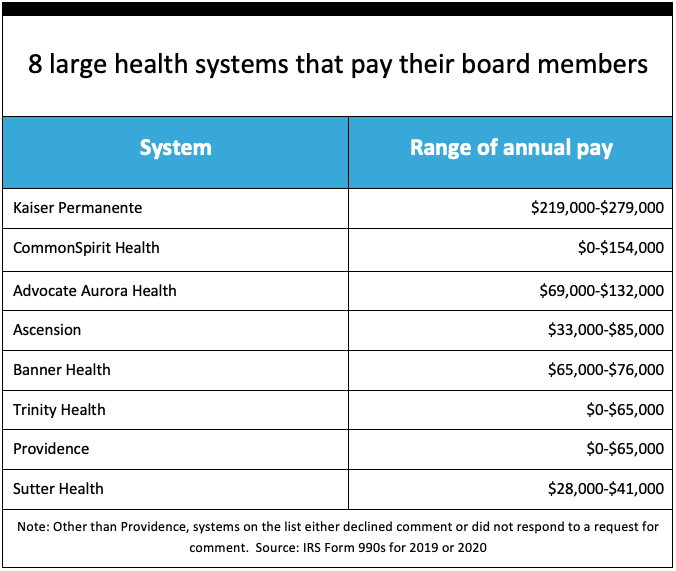

Dixon has found that among six of the largest not-for-profit healthcare systems that pay their directors, the payments generally range between $15,000 and $40,000 a year per director.

Similar results can be found in a list compiled from system tax forms.

Kaiser Permanente, the nation’s largest integrated health plan, pays its directors more than $220,000 a year, according to its tax filings.

Providence, a $5 billion system based in Renton, Washington, paid its board chair $65,000 a year and its past-chair $50,000. A few directors receive no compensation; for those who do, the amounts range from $23,000 to $46,000 a year.

“The gift of time and effort from trustees who bring an independent perspective is especially critical to our success,” said Kristina Hansen Smith, senior vice president for strategic planning, system and community governance for Providence, in written comments. “It is important to recognize the dedication of time and effort spent reviewing materials, working on projects and attending meetings on behalf of the ministry.”

Volunteering origins

The traditional model of not-for-profit governance dates to the time of Benjamin Franklin, who sat on the board of Pennsylvania Hospital. Orlikoff said the model’s explicit features are that board service is voluntary and all board members live in the community served by the hospital or other not-for-profit organization.

The board that governs UW Health, the integrated health system of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is composed of gubernatorial appointees, and board compensation may create conflict-of-interest problems, said CFO Robert Flannery. But UW Health also is served by subsidiary community boards of volunteers. Participating on any of the health system boards is seen as community service, he said.

“We have really devoted people who want to give back to the community in which they currently reside,” he said. “And I think they legally could be compensated, but it’s not been part of our history.”

The local resident aspect of the traditional model can be important in mergers and acquisitions deal-making, when board members can act as a line of defense for a hospital or regional system being acquired by a larger health system that doesn’t have a local tie.

Nevertheless, Orlikoff said that not-for-profit board service for many organizations has historically been seen as honorific, with board members expected to approve executive decisions.

Currently, the most pressing reason why a provider would compensate directors is that their roles have become much more complex and time-consuming, especially since the pandemic began. Board members must not only guide health systems through perilous situations but also be sufficiently knowledgeable on topics that range from cybersecurity to compliance to capital finance.

Meanwhile, the pandemic also has forced boards to deal with the emotional trauma experienced by clinicians and executives alike.

“For example, many boards intentionally chose to approve the crisis standards of care that their organizations used [during the pandemic]; so suddenly, you have boards involved in ‘who lives and who dies?’ decisions,” Orlikoff said.

Further rationales for compensating directors

Discussions about director compensation also have been fueled by the following considerations.

The goal of increasing board diversity to reflect the makeup of the community. “You have to recruit to attract those candidates and, because diversity/equity/inclusion has become a universal issue for almost all organizations in the U.S., there are a lot of people competing for talent,” Dixon said.

The need for an intense new board member orientation process. Directors need to know about many topics that are unique to health system governance.

The potential liability associated with board service. “The single greatest exposure of board member liability is the credentialing function,” Orlikoff said. “You can be sued by disgruntled physicians alleging restraint of trade. You can be sued by families of deceased patients.”

The trend of recruiting healthcare professionals who are retired or working for a system in another market. “You take someone who is an expert outside of healthcare and the learning curve for them to learn just the basics is so steep that they can’t really be an effective performing board member for a few years,” Orlikoff said.

The difficulty in recruiting and retaining good board members. “I’ve seen half a dozen systems in the last six months where the issue of board chair succession was not [that there were] too many candidates, but that no one wanted to do it because it takes too much time,” Orlikoff said.

Compensation rules

The vast majority of health systems that have never considered board director/member compensation just assumed they shouldn’t do it or couldn’t do it, and that’s not true, Dixon said.

While not-for-profit boards are legally allowed to pay directors, they must comply with regulations to keep their tax-exempt status, he said. This includes ensuring that the compensation is reasonable and is disclosed in tax filings.

At Providence, its governance office engages an independent third party to conduct a market review of director compensation at least every three years and provide an opinion that supports it as reasonable and appropriate, Smith said.

“All such compensation must be consistent with Providence governance compensation policy and must be approved by our sponsors council,” she said.

“I think this is a serious subject that requires every health system to really think about,” Dixon said. “And whether they judge to do it or not, they ought to really consider every facet of why or why not.”

Small hospitals left out for now

The trend of paying hospital board members likely will be limited to large systems for the foreseeable future. But small hospitals face the same complex challenges that huge systems do, and some may choose to pay their directors. Dave Muhs, CFO at Henry County Health Center, serving southeastern Iowa with 25 acute-care beds and a 49-bed long-term care facility, said the demands on board members are greater than ever before.

New board members need considerable education to be effective, but not everyone is able to take the time to attend conferences to get the necessary training.

“We’re going to have to get to the point of giving them compensation because time is scarce for everybody right now, and I don’t know if it’s feasible to continue to ask people to serve in those roles on a voluntary basis,” he said.

In Iowa, 42 of the state’s 110 hospitals are supported by county taxes; by law, directors are elected by popular vote and serve with no pay. But a bill introduced to the state legislature this year would, if passed, allow those directors to be compensated.

The Iowa Hospital Association did not initiate the bill, but it is supportive.

“It will encourage more participation in these elected seats and will benefit our public hospitals,” said Roxanne Strike, the association’s communications director, said via email. “The bill is … not a mandate. If passed, the decision will be up to each county hospital whether they compensate their trustees and for how much.” — Lola Butcher