Norton Healthcare and other health systems are making big moves to reduce health inequity

The systems are committing money and resources at a time in which the financial outlook is uncertain.

When Louisville police officers killed Breonna Taylor, a young Black woman not suspected of any crime, in her home in March 2020, the president and CEO of Norton Healthcare took it personally.

“As an employer of 18,000 people and a very prominent organization in our community, we needed to be the ones to step up and take a leadership role in health inequities and in racial inequities as well,” said Russell F. Cox, president and CEO of Louisville’s largest health system.

At the time, a new $70 million hospital in West Louisville was not on Norton’s radar screen. But Cox and his colleagues knew that lack of access to healthcare services in Louisville’s underserved West End was an example of systemic racism that fueled racial and health inequities.

The Norton West Louisville Hospital will open its doors in 2024 with plans for 20 inpatient beds and a full complement of outpatient services, giving Louisville’s West End its first hospital in more than 150 years.

Norton was one of many health systems that pledged a new focus on health equity in 2020, when two jolts — the huge gap in COVID-19 death rates between different racial populations and the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer — showed how deadly systemic racism can be.

In Norton’s case, the pledge was not an empty promise. Cox, a hospital administrator for more than three decades, intends to evaluate the hospital’s ROI in a new way — less on the financial return and more on saving lives.

“Our success is going to be measured by changing the life-expectancy disparity between ZIP codes and by reducing the incidence of cancer and hypertension and other diseases,” Cox said. “Did we, in fact, move the needle on indicators of health status? Did we level the playing field on access?”

OLD STORY, NEW PLAYBOOK

America’s legacy of health and healthcare disparities related to race, socioeconomic status, language and other attributes has been documented for decades, prompting action of various types in the industry.

The American Hospital Association (AHA), the Association of American Medical Colleges and other major organizations announced the National Call to Action to Eliminate Health Care Disparities in 2011. Since 2015, nearly 1,700 hospitals have signed the AHA’s Equity Pledge to Act.

In many cases, health equity initiatives announced in 2020 echoed previous commitments from hospitals and health systems.

“What is going to make it different this time?” asked Joy Lewis, the AHA’s senior vice president for health equity strategies. “What’s the mobilization going to look like?”

She points to two potential game-changers. The first is accountability. As of Jan. 1, CMS began tying hospital payments to reporting on three health-equity-related measures. At the same time, the Joint Commission is introducing standards to reduce healthcare disparities in its accreditation programs, including hospital accreditation.

The other difference is a societal shift.

“We’re at a point now where people are much more willing to lean into these awkward and difficult conversations,” said Lewis, who is also executive director of the AHA’s Institute for Diversity and Health Equity. “Terms like structural racism are now cocktail-party conversation. We just weren’t there two or three years ago.”

Health systems and hospitals need help knowing what to do to fulfill their equity pledges, Lewis said. To that end, the AHA introduced a Health Equity Roadmap with action steps, starting with an organizational self-assessment.

“Our members are chomping at the bit for actionable solutions to move the needle in the equity space,” Lewis said. “The roadmap is the answer to our members saying, ‘Yes, we took the pledge, but we don’t know what next to do.’”

The AHA’s goal is for 1,000 hospitals to adopt the Health Equity Roadmap by April, the one-year anniversary of its launch. But Lewis acknowledges that some health systems will find it hard to prioritize new initiatives because of the difficult business environment.

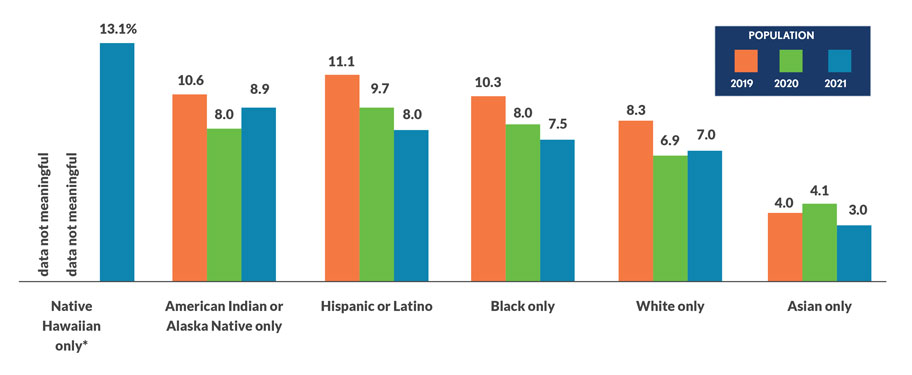

Some disparities improve, others persist

Percentage of people unable to obtain or have put off needed medical care due to cost

Sources: National Health Interview Survey, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics

Given the financial struggles hospitals are facing, a review of program spending is likely to occur, meaning there could be cuts to operations, including health equity initiatives, she said.

Health equity doesn’t have to be a stand-alone effort; it can be part of larger efforts.

“How do we look at our current and expanded efforts to serve a community through a health equity lens?” asked Rick Gundling, HFMA senior vice president for healthcare financial practices.

For example, charity-care records can be analyzed to determine whether financial assistance is equitably distributed among the various racial and ethnic groups that make up the patient population. And that there are no unintended consequences.

Use patterns are also revealing: Do certain demographic groups show up only in the emergency department because they do not access care in other settings? Those analyses can point the way to changes that need to be made to create a more equitable organization.

WHAT IS THE PRIORITY?

Whatever approach a health system takes to improving equity will work only if equity is a higher priority than money, said John W. Bluford, founder and president of the Bluford Healthcare Leadership Institute.

Bluford chaired the AHA Board of Trustees in 2011 when it led the national call to eliminate health disparities. The lack of widespread progress toward that goal reflects health systems’ tendency to prioritize financial success over other measures, Bluford said. Most nonprofit systems have a mission statement that includes improving the health of their community, but do not hold themselves to account for doing so, he said.

“If that’s your mission, success is not measured by whether you had an 8% positive bottom line, but did you reduce mortality rates by X percent? Did you reduce low-birth-weight births by X percent? Has infant mortality improved in your community?” he said. “The mission can’t be improving the health of your community when year after year after year the community health status gets worse.”

Bluford retired in 2014 after 15 years as the president and CEO of Truman Medical Centers in Kansas City, a system that has been identified as a leader nationally for educational, income and racial inclusivity. The system recently was named the most inclusive health system out of 305 in the Lown Institute’s 2022 Hospitals Index subrankings.The nonprofit Lown Institute publishes a ranking of hospitals based on how well the demographics of a hospital’s patients match those of the hospital’s service area.

The metric is a proxy for access to hospital services, which is only one part of health equity, said cardiologist Vikas Saini, MD, Lown’s president.

“But it is an important one because the hospitals that people go to seem to be determining some of the disparities,” he said. “I think our measure reflects some very deep structural elements of disparities in access and the way our healthcare system is organized.”

In many cities, one hospital attracts a whiter, wealthier, more-educated patient base while another hospital serves more people of color and those who are less affluent. None of the top 20 hospitals in the U.S. News Honor Roll get high marks in Lown’s racial inclusivity rankings, and some of them lie near the bottom of the list.

“The hospitals didn’t conspire to do this,” Saini said. “This is a legacy of many, many things.”

But creating true access — in which all people feel comfortable establishing an ongoing relationship with a provider organization — may be the best way to reduce health outcome disparities.

“It takes raising critical questions about where investments are made and why, where you decide to place your billboards, which services you’re advertising, where you’re placing a community clinic, which practices you’re trying to buy,” Saini said.

Diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives that increase board, leadership and staff diversity will not improve equity by themselves, although they are part of the solution. As the importance of equity is elevated within an organization, inequitable policies and processes are more easily seen, which is the first step to remediation.

Saini points to a hospital where Black patients with heart failure tended to be admitted to the general medicine wards, while white patients were admitted to the cardiology service.

“That was a difference, not just of location, but of staffing and the skill sets of the doctors and the nurses,” he said. “Why was that happening? Nobody was sitting around saying, ‘Let’s do this.’ These are unconscious biases, and it is important to develop programs to address them.”

EQUITY SUPPORTS VALUE

Nemours Children’s Health, an integrated pediatric health system, in 2021 received $25 million in philanthropic funding to advance health equity for children in medically underserved areas. System executives aspire to start a national policy discussion on health equity for children and conduct research, education and quality improvement initiatives.

The work dovetails into Nemours’ efforts to partner with payers to reduce inequities.

“Equity is a part of quality,” said Karen Wilding, the system’s chief value officer. “Are we really achieving value if we aren’t addressing equity?”

Nemours includes two children’s hospitals — one in Orlando, another in Wilmington, Delaware — and more than 70 outpatient groups.

Wilding facilitates partnerships with payers to design value-based payment and care models that support Nemours’ “pay-for-health” philosophy. The system’s ability to improve children’s health at the population level was demonstrated in the first year of a collaboration.

An analysis of care provided in 2021 to 6,500 children covered by Florida Blue, a Blue Cross Blue Shield plan, showed that Nemours slowed its cost growth to 3.6%, compared with 7% for similar providers, while increasing immunizations, preventative screenings and wellness visits. Key to its strategy were care-management services that helped reduce hospital readmissions by 24%.

Nemours is building on that by collaborating with AmeriHealth Caritas Delaware, a Medicaid managed care health plan, and Delaware’s Medicaid program. The three are participating in the Advancing Health Equity program funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

AmeriHealth and Nemours are working to understand the care gaps that create health inequities among the members/patients they share. The first step is to format the data to stratify patients by race, language and other variables.

“We may see, for example, children with asthma who speak a certain language are in need of focused attention,” Wilding said. “So based on that shared priority, we can make very intentional investments such as working on our educational materials or changing how we follow those children.”

THE CFO’S ROLE IN EQUITY

Improving health equity requires leadership and authority, both of which fit into the CFO’s job description.

“They can be very influential in setting metrics that define success in the mission of creating a healthy community,” Bluford said. “To the extent that they can put numbers, and perhaps even dollars, around chronic disease management, mortality and morbidity rates, and how readmission rates relate to the social determinants of health, they can make a case that more resources need to be dedicated to those things that I call ‘thinking outside of the bed.’”

HFMA’s Gundling points to the CFO’s inherent strengths of creating a strategy and executing on it.

“They can contribute to the health equity strategy and also help focus on goals,” he said.

Further, he said, CFOs may be able to help overcome barriers to advancing equity. Socioeconomic and other data that clinicians need to support targeted interventions may be sitting in the health system’s billing system, waiting for the leader who can unlock it.

And CFOs can articulate the link between advancing health equity and fulfilling community-benefit obligations needed to qualify for tax-exempt status.

“Health systems need to keep the financial dimension front and center, and I understand that,” said the Lown Institute’s Saini. “But to the extent we want to do the work we all signed up for, we have to start thinking about equity through another lens. If you don’t, improvement is not going to happen by itself.”