Healthcare 2030: The Next Generation Public Health System

The nation’s public health system needs a revamp, but there isn’t a single stakeholder with the knowledge and resources to lead that effort.

By JENI WILLIAMS, HFMA CONTRIBUTING WRITER

| COVID-19 exposed the limits of the U.S. public health infrastructure in responding to health crises. Those limits fed into inequities in the nation’s public health response for underserved populations. It also hindered efforts to contain the virus and fueled distrust in public health agencies and systems of care. |

|

Now, the pandemic-related breakdowns in public health have invited careful examination of the resources, capabilities and infrastructure needed to create a next-generation public health system. And healthcare leaders must consider what more they can and should do. “What will the role of health systems be in a revamped public health model — one that emphasizes wellness, prevention and protection?” said Karen DeSalvo, MD, chief health officer for Google, speaking at the HFMA Annual Conference in June. “Health is more than healthcare,” said DeSalvo, who was acting assistant secretary for health and the national coordinator for health information technology at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under President Barack Obama. |

For healthcare finance leaders in particular, a reimagining of public health presents an opportunity to take a front seat — if not the driver’s seat — in transforming the nation’s health infrastructure to deliver more value to more people in more sustainable ways.

Reversing years of chronic underinvestment in public health could reduce the frequency and severity of public health threats, easing the strain on health system resources and staff and strengthening the ability to connect with patients and address social determinants of health (SDoH). It would also bolster the ability of health systems and public health agencies to deliver the right data to the right people at the right time, speeding response times and eliminating the confusion that results when accurate data is not available.

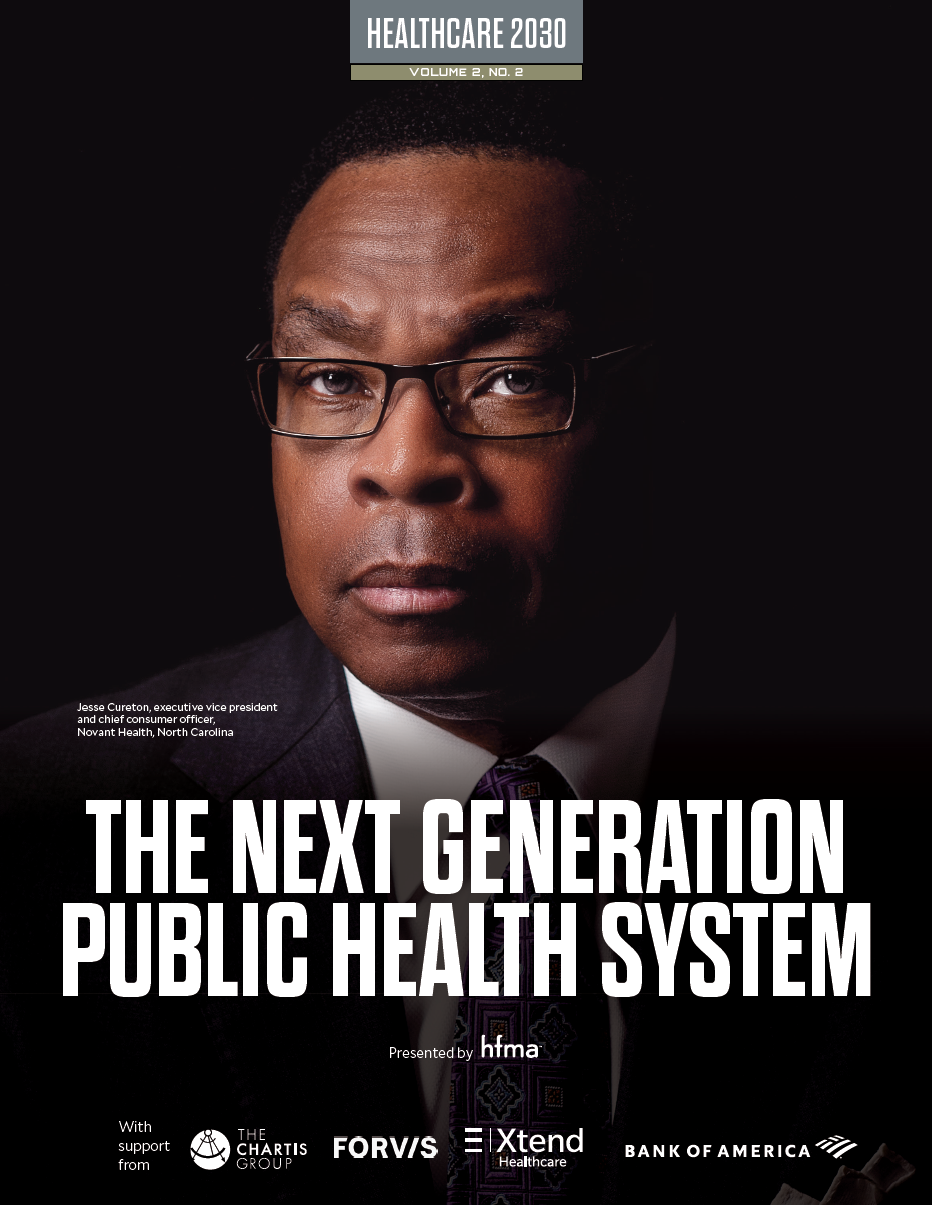

Jesse Cureton, executive vice president and chief consumer officer, Novant Health, North Carolina

“When you think about the extent to which misinformation around COVID-19 proliferated during the pandemic, some health systems did not respond as quickly in providing the information consumers needed most, from when to get tested to where to receive a vaccine,” said Jesse Cureton, executive vice president and chief consumer officer for Novant Health, Charlotte, North Carolina.

The public health system of the future must develop mechanisms for understanding where health pain points exist and responding to these needs in ways that deepen relationships with the populations they serve.

“Every one of our patients wants to feel that their care has been built around their specific needs,” Cureton said.

“Our patients are regularly surveyed after their visit, and we have dedicated patient experience teams that review the surveys and identify what is going well and where there are opportunities to improve,” Cureton said. “We also have a robust advisory council that comprises nearly 8,000 patients and community members who provide feedback on innovations, services and features we offer. This feedback allows us to match our capabilities to our communities and make it easy for consumers to interact with us, which builds trust around our work.”

Deepening relationships with consumers also require health systems and public health institutions to understand that they cannot reach every population in one manner.

Nancy Johnson, retired CEO of El Rio Health Center in Tucson, Arizona

“That’s one of the challenges of a system that is basically designed to take care of everybody,” said Nancy Johnson, who recently retired from her role as CEO of El Rio Health Center, one of the nation’s largest federally qualified health centers, located in Tucson, Arizona. “Not everyone navigates the world in the same way. A [larger] health system might have the resources to create equity in care access and intervention, but most health systems cannot meet every healthcare need for every individual.”

Remaking the culture for emergency response: National experts weigh in

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced sweeping changes to help speed the agency’s response to public health crises this past August. But creating a culture of fast action when public health is at risk depends on maintaining the infrastructure for efficient response, a concept that will be new to the CDC and other federal agencies.

“How do we maintain the systems put in place during the pandemic and show that we are always prepared so that when things like COVID-19 happen, it’s not another scramble to figure out what to do next?” said Dave Wojs, Jr., senior director of public health for Juvare, a provider of emergency preparedness and response software.

“One of the problems we have in public health is that policy makers defund emergency preparedness and response too easily,” said Wojs, who has 17 years of experience in public health, including more than a decade in emergency preparedness and response. “We surge these emergency fundings, ramp things up, build systems out, finally start getting some trust back, and then the event is over, and we turn everything off.”

He cites HAvBED, the Hospital Available Beds for Emergencies and Disasters reporting system, as an example. Initiated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, HAvBED required states to develop the capability to collect and report hospital available bed information to gauge health system capacity and demand in real time. The system was designed to strengthen emergency response in the event of a public health event or mass casualty. But the federal government discontinued this program a few months before COVID-19 emerged because there had not been a need for this system in several years.

The problem, Wojs said, is that once emergency response systems such as these are disconnected, it takes a long time to rebuild the connections, including the security clearances, usernames and passwords required to gain access to these systems. This is especially true in healthcare, he said.

“Luckily for most states, they didn’t disassemble their internal data collection capabilities,” Wojs said. “What they did was turn off the ability to send the data to the federal government. This was brilliant from the state perspective. State and local health departments really get the win for that. Long term, we need to keep systems like these and the people who understand the intricacies of these systems in place so that emergency response does not become an ‘all other duties as assigned’ type of function when the current public health crisis is over.”

Balancing act

Health systems and public health institutions of the future will need to determine how to operate in ways that support the health of their population — alone or in partnership with others — while recognizing that their staff are human beings with limits, Johnson said. Key to this effort: data that help health leaders understand the burden of poverty in their communities, the ways in which poverty impacts health and the challenges patients face in accessing care that meets their needs. Such data also can help point to what’s working — and what isn’t — in engaging highly diverse and highly complex populations, such as Medicare and Medicaid members, around their health.

“How do we create great experiences for people, so they want to engage in their care?” Johnson said.

Cultural competency training and education around implicit bias has helped team members build stronger connections with consumers while recognizing the impact of unconscious biases on healthcare teams and their patients, Cureton said. At Novant Health, more than 95% of physicians, advanced practice providers and other team members who have taken part in this training believe the content was “extremely valuable” and bolstered their ability to create unique, patient-centric, culturally sensitive interactions with patients.

“In our experience, there are some consumers who prefer all contact to come from primary care physicians,” Cureton said.

Whose job is it?

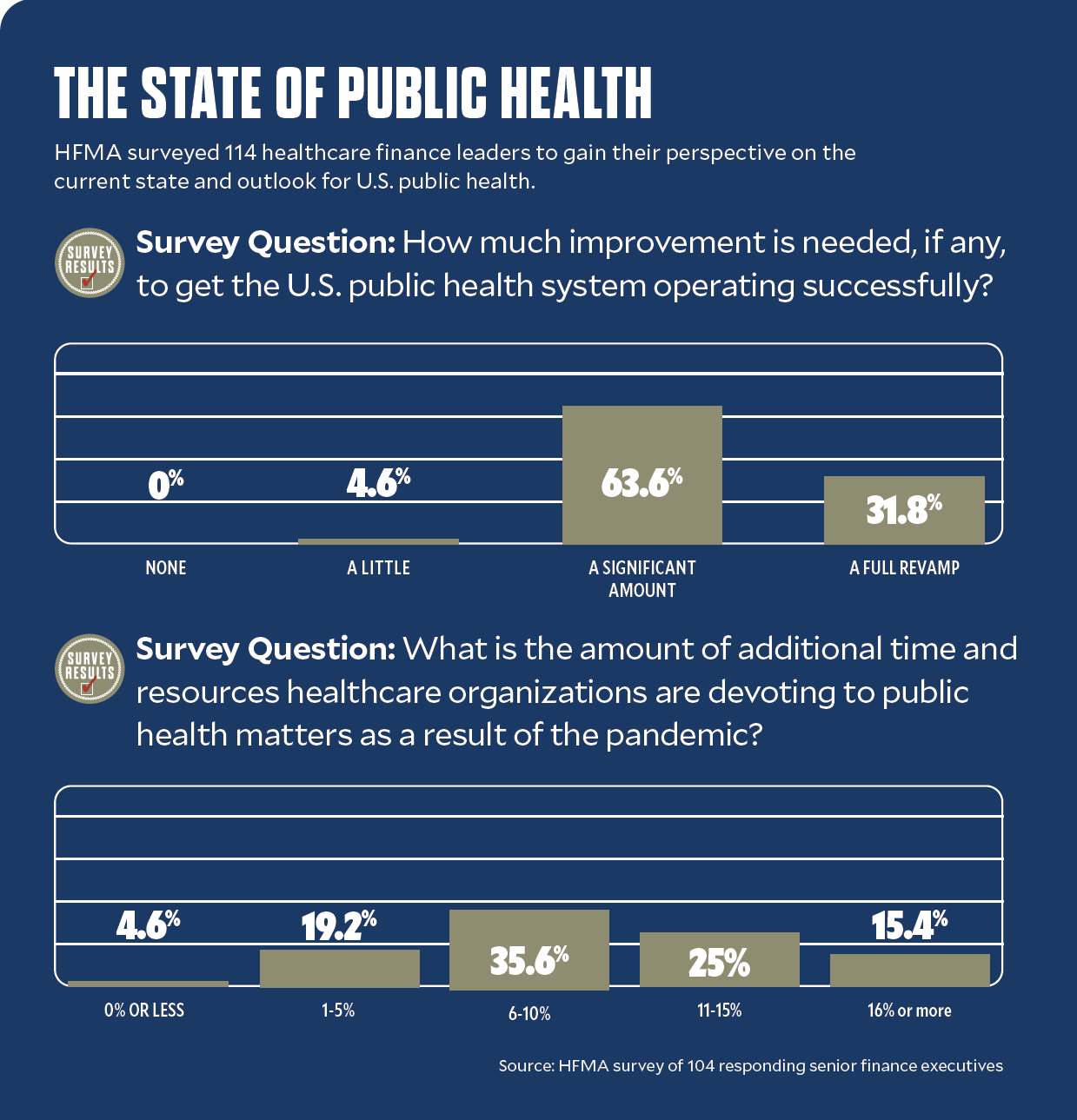

A recent HFMA survey of healthcare executives shows more than 60% believe hospitals and health systems should play a major role in public health, and another 18% believe these organizations should have a leading role. For these leaders, the task of revamping public health looms large. Three out of five healthcare executives surveyed say it would take a significant amount of improvement to get the public health system to operate successfully. About one out of three say it would take “a full revamp” to accomplish this goal.

Prioritizing public health could pay big dividends. McKinsey & Company estimates that every dollar invested in public health infrastructure improvement could lead to a $2 to $4 economic return, such as by extending lifespans for workers.

Yet without a well-funded approach, management of public health will remain a piecemeal effort instead of the comprehensive, wellness-focused model that is needed.

“Partnerships are going to be massively consequential in changing health outcomes for vulnerable populations,” said Denese Neu, a former engagement officer for the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and currently a consultant for Friedman Associates.

Also important will be ensuring health institutions and systems devote the right resources to the right problems. Hospitals are not always the best choice to tackle a given problem.

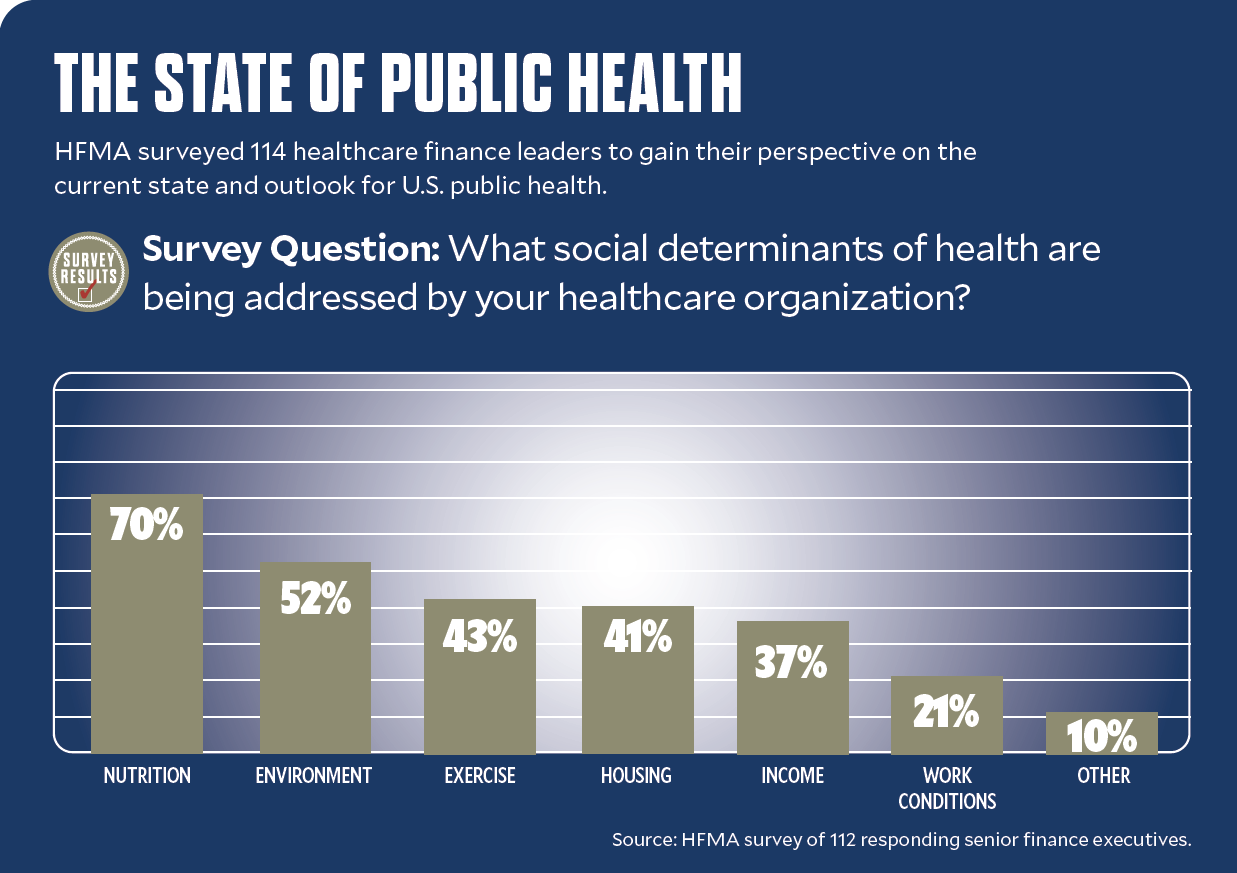

“I’m a little nervous about the increased amount of pressure that has been put on the healthcare system to do things like build affordable housing,” said Neu, who has more than three decades of experience in healthcare, much of it at the intersection of community and economic development and health. By 2020, health systems had invested $2.5 billion in SDoH initiatives, and CMS more recently has proposed quality measures related to SDoH screening and response.

As awareness grows that SDoH — the conditions in which people live, work, grow and age — have a large proportional effect on health outcomes, health systems increasingly have sought to take an active role in addressing SDoH in their communities.

Some grow community gardens or create food banks to help vulnerable populations gain access to healthy food. Some invest in initiatives that support affordable housing, access to reliable transportation, education and employment security.

“There’s a whole industry out there that has been doing that work for decades,” Neu said. “What would make more sense is for health systems to work in tandem with an affordable housing provider to offer wraparound services that improve health and health literacy for low-income residents — efforts that connect directly to these organizations’ mission and their core competencies.”

Key federal actions needed

Key actions the CDC and other federal agencies should consider supporting for a faster, more efficient public health response include the following.

✔ Develop a more aggressive, forward-leaning, data-informed emergency health response.

“We’ve got to move from a contemplative, pretty slow system that tries to improve public health to a system that can more easily get in front of infectious disease outbreaks,” said Georges C. Benjamin, MD, executive director for the American Public Health Association. This will require a much more robust information highway.

“Right now, we don’t have a national data system that is interoperable and allows us to share information in a timely way,” Benjamin said. “The fact that we still have places in the United States where you can’t move an EKG across the street without a fax machine is a problem. And often, we’re making health decisions on old data. We’ve got to have a more robust system for sharing health information. The technology is there to do it. We just don’t have the system.”

✔ Modernize legacy systems for data sharing and collection at the federal level.

“They have to chart their course to modernization” said Dave Wojs, senior director of public health for Juvare. Many of the information systems at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are custom built for the agency, and the old custom software development mindset and mentality is just not going to work in the future of public health, he said. Systems are needed that can share data using a common standard.

✔ Establish a more definitive plan for which government agency will lead the public health response during a crisis.

“We move the stages of a response between organizations too much,” Wojs said. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the CDC initially led the public health response; then, responsibility shifted to what is now the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR). Now, during the monkeypox outbreak, officials from the CDC and the Federal Emergency Management Agency have been appointed to combat the outbreak. With the Office of the ASPR being elevated to an operating division, there’s more hope that some of these responses will find the appropriate home sooner, Wojs said.

A losing proposition

Brian Castrucci, DrPH, MA, president and CEO of the de Beaumont Foundation

Neu’s feelings were echoed by Brian C. Castrucci, DrPH, MA, president and CEO of the de Beaumont Foundation, a leading voice in public health practice. Castrucci sees directing health systems’ clinical resources toward solving SDoH as a losing proposition.

One key opportunity healthcare leaders have to move the needle on public health is to collaborate with public health agencies around community benefit activities, said Georges C. Benjamin, MD, executive director for the American Public Health Association, based in Washington, D.C.

“Many healthcare organizations are doing their own community health needs assessments, but in many ways, these efforts duplicate the work of public health departments,” Benjamin said. “By working together with health departments and even competing health systems, organizations can do these assessments together, agree on what the priorities are in their communities and then decide who is going to coordinate those activities. There are many places across the country where competing health systems have partnered with health departments to undertake this work. These systems collaborate around some services and compete heavily on others.”

Healthcare also must embrace its nonclinical power to influence policy and partnerships if it is to make a significant impact on SDoH.

“As long as healthcare is trying to be an anchor institution, it will not be a change agent — using its influence to change policy and drive partnerships that optimize health,” Castrucci said.

“I hope that’s what healthcare is by 2030: a change agent,” Benjamin said. “Because unless healthcare leaders take an active role in influencing policy, they will not be fulfilling their organization’s mission.”

Benjamin noted that hospitals and health systems possess extraordinary political power because they typically are the largest employers in their communities and carry clout.

Step up policy-focused efforts

Often, hospitals, in particular, spend time addressing the social-service needs of their patients when they could influence policy issues that affect the health of their communities. They could also play a role in ensuring local, state and national budgets adequately support public health and emergency response. Even zoning board meetings offer healthcare leaders an opportunity to weigh in on public health, given the correlation between liquor store density and alcohol use and substance use disorder.

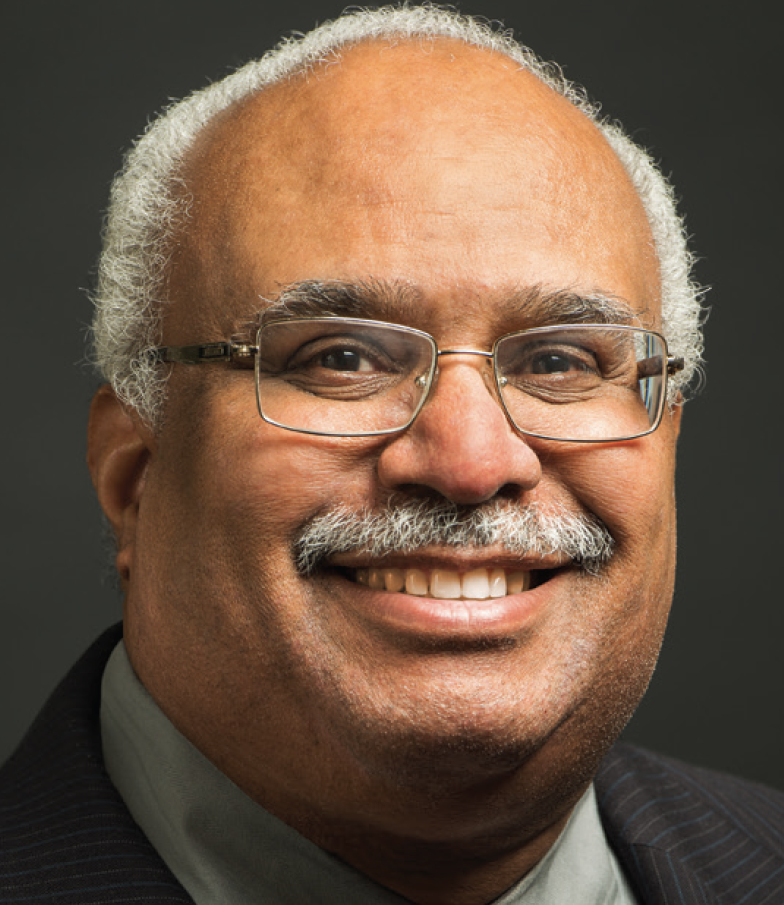

Georges C. Benjamin, executive director for the American Public Health Association

“I would encourage hospitals to spend time on policy issues that directly affect their own institutions,” Benjamin said. “During my time as a public health officer, I’ve found that the room is always packed when people are talking about big-money issues like Medicaid reimbursement, but when a local public health department holds a hearing on its budget, attendance is much lower.

“Hospitals should take a careful look at their public health department’s budget for infectious disease, laboratory expenses, and prevention and wellness. This is an area where healthcare leaders could contribute insight for the health and well-being of their community.”

Technology is another area of uncertainty, because some patients have little to no access to it or awareness of how it can be used and can help.

Rebuilding connections with communities

Ultimately, the success of the public health model of the future will depend not just on technological innovation, but also on a rethinking of the ways in which hospitals and health systems build relationships with the populations they serve. These efforts will be key to strengthening the public health response during a crisis. They will also be central to restoring public trust in healthcare agencies and institutions.

“We have some work to do around public trust,” said Benjamin. “Trust is hard to gather and easy to lose. Public trust comes because people feel they are valued, they’ve been treated with dignity, and people do what they say they’re going to do. I would argue most medical practices do this quite well. But there are some that don’t. And we have to improve performance on that. One of the challenges we’ve had, particularly with minority communities, is that they often feel they were disrespected not 10 years ago when they went into the healthcare system, but yesterday. That has to change.”

In this era of change, the new mandate for healthcare leaders is to help lay the groundwork for innovations that improve communication as well as care access, delivery and outcomes. It’s a mandate that healthcare CFOs in particular are well-positioned to execute upon.

“Innovation is not an ideas problem, but a resource allocation problem, [and] no one is better positioned than the CFO to help identify, select and refine the value proposition of ideas,” Zeev Neuwirth, MD, a physician executive and author of Reframing Healthcare: A Roadmap for Creating Disruptive Change, told healthcare finance professionals at the HFMA Annual Conference. “We need your financial expertise, but we also need your bold, courageous and humanistic leadership.”

Technology’s promise and peril for public health

It’s no surprise that the pandemic informed or accelerated many of the changes that will define the public health system of the future. What will define healthcare organizations’ roles in the future is the extent to which they embrace disruption and engage their teams in the transformational change needed to evolve.

“Disruption is not all bad. It causes us to pause; it causes us to question whether we can do things differently,” said Jesse Cureton, executive vice president and chief consumer officer for Novant Health. “At the end of the day, we think disruption is going to be really good for our business, and we embrace it. We’re going to create some of it. Ultimately, our consumers will benefit.”

Since the pandemic emerged, the application of technology to expand access to medical expertise across borders and provide care on-demand and in the home has revolutionized care for some.

Innovations in tech-assisted care, meanwhile, help healthcare professionals work at the top of their license — a move that not only reduces costs of care, but also eases the administrative demands that can lead to burnout. In many instances, staff members like medical assistants and community health outreach workers can be trained to perform tasks that achieve better health outcomes, such as checking medication adherence, while saving money overall, said Nancy Johnson, recently retired CEO of El Rio Health Center. Here, too, efforts to change policy — such as regulations that stipulate only licensed physicians and a small number of other health professionals can bill for services rendered — could make a significant difference.

Public not completely ready

But achieving the promise of technological innovations in care means helping the public understand the role of technology as a care augmenter as the industry moves toward an even more tech-enabled health system of the future. It requires that technologies be designed with the needs of disadvantaged and medically complex patient populations in mind and distributed to those who would most benefit. Access to telehealth alone remains uneven. Even as virtual care proliferated during the pandemic, one out of five patients at a Boston hospital indicated they did not have access to a connected device with a camera or microphone to facilitate telehealth access. Further, 25% of American adults do not have broadband access at home.