A Blueprint for Building a ‘Risk Ready’ Healthcare Organization

The same infrastructure a healthcare organization uses to negotiate a risk-based contract also is essential to operating effectively under the contract.

Facing growing pressure from insurers to assume more financial risk, healthcare providers are exploring ways to better manage cost and utilization through risk-based contracts.

Unfortunately, the approaches these organizations have adopted are too often inadequate, because their executive teams are giving most of their attention to the contract itself and not enough thought to what they will do once the agreement is signed. Although several health systems have found success in risk-based contracting, achieving that success required a significant transformation in management and care delivery.

Effective contract negotiation and contract execution depend on the same set of capabilities. To succeed in risk-based contracting, providers need to build an infrastructure that supports every dimension of risk management—from risk modeling and contract design to population health strategy.

Creating this infrastructure requires a focus on developing four cornerstone capabilities:

- Contract modeling and negotiation

- Care management and coordination

- Analytics and technology

- Relationships and alignment

Contract Modeling and Negotiation

The first step is to use cost and contract modeling to gain an accurate understanding of your patient population, where the word cost refers to the medical spend attributed to patients or populations. The main reason organizations fail at risk-based contracting is that they are unable to effectively manage the cost of their attributed populations. Successful provider organizations have developed capabilities for developing accurate cost models and using them to identify and manage risk. The best-practice steps in this process are as follows.

Define the attributed population. It is best to begin by clearly delineating the population under management using an attribution model that differentiates patients who are members of the population under management from those who are not. There are two main models: one based on provider volume and one based on geographic distribution.

Under the provider volume model, patients are attributed to the physician they see most often during a performance year. The benefit of this model is that a healthcare organization’s attributed population coincides with the group of patients it has most influence over. The downside is the model’s complexity. Consider this scenario: During a performance year, a patient is seen three times by a primary care physician in the provider’s network and three times by an outside cardiologist. Which network should the patient be attributed to? To answer this question, the attribution methodology must consider total claims, level of care, and other parameters.

Under the geographic distribution model, a provider organization assumes risk for all patients within one or more defined ZIP codes. This approach is straightforward, but it comes with significant risk of network leakage. Success under this model will likely be limited to organizations with sufficient market penetration to effectively manage an entire geography.

Start building the cost model. Understanding the population’s medical spend “costs” and building effective cost allocation are prospects that continue to challenge both providers and insurers. The key is to create a basic cost model and refine it as the organization gains experience.

The starting point is claims analysis. Early in the negotiation process for a risk-based contract, the provider organization should request a sample claims file from the insurer. This sample should contain 18 to 24 months of claims for 15 to 25 percent of the population to be managed, and it should provide a good representation of the population’s risk diversity.

To create the basic model, it is necessary to divide the population’s total monthly claims for medical services and pharmaceuticals by the total number of patients (or in insurer terminology, the total number of “members”). This is the per-member-per-month (PMPM) cost for the population under management.

The data then should be analyzed by medical spend and utilization to ascertain, for example, how costs are distributed among the population and where utilization is highest and lowest in different care settings. Such analyses will provide insights into the current health and cost status of the population and help identify the organization’s contracting opportunities.

Identify and carve out risk. Next, the provider organization should identify any costs it wants to exclude from the PMPM calculation. In general, providers want to carve out catastrophic costs and difficult-to-control risks—excluding members with claims over $100,000, for example.

Providers should be aware, however, that insurers are increasingly pressing them to manage high-risk patients. Consider, for example, a hospital that does not provide heart transplant and therefore moves to exclude costs related to high-risk coronary artery disease. The insurer might push back, arguing that the hospital should partner with a tertiary care center to provide and manage high-risk services under one contractual umbrella.

Think in terms of reconciliation methodology. At the end of every performance period for a risk-based contract, the insurer and the provider must determine whether actual PMPM exceeded or fell short of the medical spend cost target. If the methodology is not well defined, the reconciliation process can be a source of time-consuming conflict. Common problems include ambiguity regarding the following:

- Baseline periods—it is important to define the specific service dates that will be used to determine initial PMPM targets.

- Patient opt-in/opt-out issues—there should be rules defining how patients and providers enter and exit the attributed population.

- Contractual exclusions—it should be clear which costs are and are not included in the agreement.

When negotiating carve-outs, attribution rules, and other issues, there is often no one right answer. Different terms can work for different organizations. The main point is that providers should never enter any risk-based contract without a full understanding of how the costs are calculated, all the elements that go into the reconciliation formula, and how these decisions will impact the organization.

Care Management and Coordination

To optimize a risk-based contract, a provider organization must be able to control all the factors that influence the medical spend and quality outcomes within the managed population. The key is to address risk through effective care management. The organization should begin this process by reexamining its care management strategy to ensure it includes the following tactics.

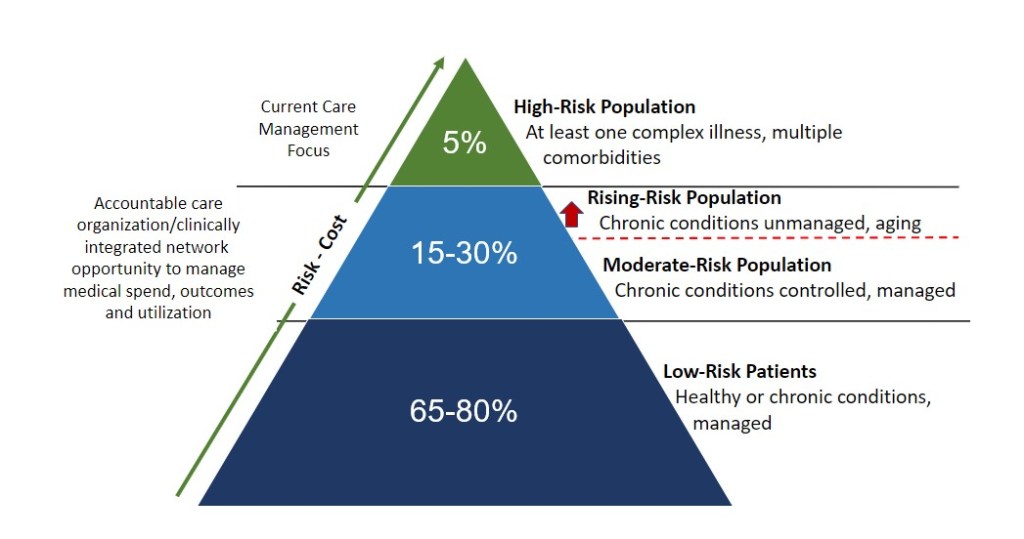

Expand the focus to “rising risk” patients. Over the past 10 years, most risk-based contracts have involved “upside-only” shared savings contracts. The lack of downside exposure gave providers an incentive to focus on high-risk patients—the sickest 5 percent of the patient population representing the majority of costs and the best opportunity to realize significant savings.

Healthcare Risk Pyramid

As insurers move toward true risk-based contracts that include both upside and downside risk, healthcare organizations should broaden their focus to “rising risk” patients. This population can be defined as the 15 to 30 percent of the population with one or more chronic diseases (as shown in the exhibit above). These patients typically are older, and their illnesses often are unmanaged. Optimizing care and outcomes for these patients is the key to achieving true cost control within a broad-based population.

Leverage both provider and insurer resources. Most provider organizations understand the benefits of caremanagement, defined as using the clinical record to identify opportunities to lower costs by improving care and outcomes. Under risk-based contracts, however, providers also must manage utilization, and it makes sense that they can do so most effectively by leveraging insurer expertise in case management, defined as using claims data to lower the cost of services by managing patients across multiple networks.

Focus on managing patient leakage. Insurer-based utilization nurses can assist provider organizations by helping them understand referral patterns outside their systems. Such assistance can help the provider identify opportunities to use member outreach and develop educational initiatives to steer patients back into the organized system of care.

Pay attention to the social determinants of health. A growing body of research shows that factors such as access to transportation, food security, and social support can have a huge impact on clinical outcomes. Optimizing these factors is especially important for managing rising-risk patients, who, by definition, are on the verge of serious, high-cost health problems. Provider organizations can begin to target these factors by investing in social workers, dietitians, counselors, and other nontraditional support providers. Some organizations also are exploring the use of digital tools—smartphone apps, for example—for engaging patients and influencing outcomes.

Share infrastructure costs. Because care management is an essential element of a risk-based care model, it makes sense that insurers assume a portion of infrastructure costs. When negotiating a risk-based contract, the provider should request a PMPM care management fee. The fee may only cover 10 to 25 percent of infrastructure costs, but it will reduce the provider’s financial burden, and it can help align both parties around care management goals.

Analytics and Technology

Effective risk management requires strong data management capabilities. The key is developing analytic systems that bring together clinical and financial information. Leading organizations are focusing their efforts in the following areas.

Developing disease registries. A disease registry is a customized database for tracking a specific at-risk population, such as patients with diabetes, hypertension, or sepsis or who are in a defined “transition of care.” Registries incorporate clinical information from an electronic health record and utilization information supplied by monthly claims feeds. Care management staff use disease registries to identify and close gaps in care.

For instance, a diabetes registry could meld clinical information on all patients with a diagnosis for diabetes or a related complication with claims-based information on recent related services. Care managers could use this registry to identify all diabetic patients who have not had an A1C test or a diabetic foot exam in the previous 12 months. This information would then create the opportunity to improve care through patient outreach, referral for social support, or other interventions.

Honing systems for tracking costs and margins. The basic PMPM cost model (discussed above) is a starting point for risk-based contracting. As the organization gains experience with population health and care management, it should continuously refine the model. The goal is to evolve from limited cost-accounting tools to strong financial decision-support capabilities.

The organization’s accounting department should be charged with refining formulas for allocating fixed costs. Variable cost allocation should be addressed category by category, starting with the highest-spend items. For example, a starting point might be working with the oncology department to create a methodology for allocating chemotherapy drugs and biologicals.

Performing prospective analysis and value modeling. As the organization gains experience in population management, it should begin seeking new opportunities to boost contractual performance. The organization should use clinical and financial data to create a “value model” for the network, which then can be used to identify investments likely to yield a return under a risk-based contract. An effective value model will begin to quantify the ROI from care management of risk-based populations, quantify the impact of shifts in utilization between a network’s care settings, and begin to predict outcomes for specific population cohorts.

For example, clinical and financial data might show that one geriatric care coordinator drives $250,000 in savings through reduced readmissions. By combining this information with population data, the organization can run different statistical scenarios to determine the optimal investment in additional care coordination staff, project patient outcomes of care management, and estimate the revenue impact on different places of service within the organization.

Relationships and Alignment

The principles discussed above apply to every kind of risk-based contract, not just agreements with commercial insurers. Even where negotiations with payers are limited—for instance, with Medicare Advantage—mastering these concepts is important. Medicare rules regarding attribution and other contractual terms evolve constantly, and providers need to be able to model the impact of program changes.

One overall success factor for any risk-based contract is managing relationships. Healthcare leaders should focus on three priorities.

Building physician relationships. Roughly speaking, physicians make 80 percent of the decisions that affect patient health—yet hospitals bear 80 percent of the cost of care. For a health system to perform well under risk-based contracting, it must develop strong working partnerships with physicians.

Hospitals and health systems use various measures to track and evaluate physician partnerships. The key consideration is whether the organization is tracking physician engagement or physician alignment? If it is tracking measures such as committee participation, the organization may be able to say it has an “engaged” physician staff, but that does not mean those physicians are aligned with the organization’s goals around quality and cost control.

The better strategy is to track physician alignment using measures such as preventive screening rate and generic prescribing rate. It also is important to link these measures to compensation. If, for example, 90 percent of compensation for a health system’s employed physicians is based on relative-value units (RVUs), then to achieve greater alignment, the health system might transition that compensation structure to 60 percent based on RVUs and 40 percent based on quality and outcome measures.

Managing relationships with insurers. A characteristic of successful risk-based contracts is that they are overseen by a governance group that includes both provider and insurer representatives. The governance group should meet quarterly to review 90-day performance and address problems proactively. The provider organization’s medical director also should meet with the insurer’s medical director regularly to review high-cost claims and high-risk members. Transparency and the open sharing of data are key to building trust in provider-insurer relationships.

Collaborating intelligently. Managing risk does not mean an organization has to own every part of the care delivery system. Although acquiring or merging with other provider organizations might sometimes make sense, independent organizations often can collaborate to manage populations effectively.

The key is to bring together provider organizations with different strengths. For example, an effective collaborative network might include one or more community hospitals (to provide the bulk of inpatient care), a multispecialty physician group (to take the lead on care management), an academic medical center (to deliver high-cost tertiary and quaternary care), and a variety of skilled nursing and home health agencies (to manage patients who have chronic diseases or who require post-acute care).

The goal is to create an organized system of care that can manage the full range of risks. No one organization will excel at everything, but a network that leverages individual strengths has an excellent chance of differentiating itself in the market.

The Question of Timing

What is the right time to assume risk? Although the conditions in a provider organization’s market are important, the timing ultimately depends on how soon the organization can build an infrastructure that allows it to model costs, manage populations, leverage analytics, and build effective provider coalitions. Risk-based contracting is part of the future of health care, so provider organizations should begin developing that infrastructure now.

Daniel J. Marino is managing partner, Lumina Health Partners, Chicago.