Why removing percent-of-charge provisions in managed care contracts won’t address concerns about high hospital charges

Implementing fixed-fee provisions would not remove the factors that drive price increases, nor would it reduce administrative hassles or decrease risk.

Healthcare figures to be a primary issue in the 2020 elections, with much of the focus on costs — especially hospital costs. A common concern among users of hospital services is the apparent lack of correlation between hospital charges and payment.

Although some hospital managed care executives have suggested replacing percent-of-charge (POC) contract provisions with fixed-fee payment as a solution, these proposals are based on three myths regarding the POC payment methodology relative to fixed-fee payment.

A closer look at each myth reveals that such a payment change could be problematic for the industry. A better solution is within reach, however: An indexed rate limit in POC contracts that would allow hospitals to lower charges without experiencing reductions in payments.

Sidebar: A closer look at healthcare payment models

Myth #1: Replacing POC provisions with fixed fees will remove the need to increase prices

Many managed care executives believe that replacing POC provisions with fee schedules will enable them to lower their current prices or at least restrain price increases. But consider this pricing formula:

REQUIRED PRICE = [AVERAGE COST + (REQUIRED MARGIN + LOSS ON FIXED-FEE CONTRACTS)] / [POC VOLUME × (1-AVERAGE DISCOUNT %)]

As the formula shows, the required price that any hospital must set is based on several factors.

1. Actual prices must be set at levels that exceed actual costs.

2. Hospitals, like any business, must generate a profit margin to replace their physical assets and to service debt obligations.

3. Losses on fixed-fee payment plans (stemming from fee schedules that are less than cost) must be shifted to patients who are covered by POC provisions. There would be a gain rather than a loss if actual payment exceeded incurred cost, but that outcome is unlikely given the large losses that usually result from government payment plans.

4. As POC volume shrinks, the resulting price must be increased.

Let’s use a case example to help isolate the key factors. Assume we have a POC provision that makes payment for emergency department (ED) claims at 50% of billed charges, and we want to replace that provision with a fee schedule that pays $1,000 for levels 1 and 2 emergency claims, $1,600 for level 3 claims, $4,500 for level 4 claims and $6,000 for level 5 claims. Will this change permit us to reduce our ED charges?

The answer is yes, but only if the fixed-fee payments exceed the current POC payment. If the fee schedule payment is less than the POC payment, that loss would have to be shifted to the now smaller base of POC patients, which would result in a higher required price. Negotiating a fixed-fee replacement for a POC payment makes no sense financially unless there is a significant increase in payment. Managed care payers seem unlikely to agree to increase their payment beyond current levels, meaning a reduction in charges would be improbable.

Some might argue that removing the POC provision will help reduce patient responsibility amounts. Since collectability on those amounts is not likely to be 100%, this reduction could represent a financial advantage to the hospital.

Upon examination, however, this scenario is suspect. Using the ED example, assume current pricing for a level 1 claim is $2,000. At the current 50% payment provision, expected payment would be $1,000. If the claim includes a 20% copayment provision, the patient would pay $200 based on allowed charges of $1,000, and the managed care plan would pay $800. Meanwhile, moving from the POC payment to the $1,000 fixed payment for the level 1 emergency claim would still require a 20% copayment of $200.

Even though the initial payment change might be net revenue neutral, the longer-term effect figures to be an increase in the hospital’s prices. To understand this from a mathematical perspective, review the pricing formula again. Given recent trends, government payments can be expected to erode over time. Although some of the loss will be picked up by commercial fixed-fee payments, a sizable portion will not.

That shortfall will require an even larger shift to POC plans, resulting in even larger increases in prices. With fixed payment terms in place, and an income target that is essential to preserving the financial viability of the institution, hospitals must either implement draconian cost reductions or increase prices to the smaller block of POC patients.

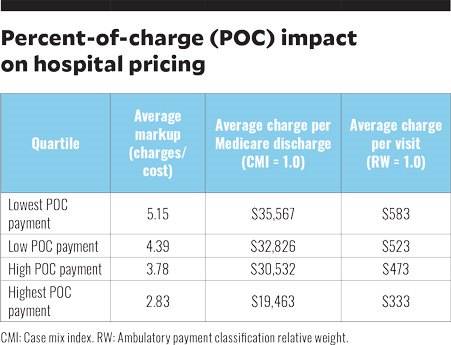

Empirical data indicates an association between lower percentages of POC payment and higher prices. We pulled data from about 300 hospitals in 2018. These were all prospective payment hospitals, with critical access hospitals and specialty hospitals excluded.

We determined the percentage of revenue derived from POC contracts and then divided the hospitals into quartiles using that metric. Using 2018 Healthcare Cost Report Information System (HCRIS) data and 2017 Medicare claims data, we then computed the average values for three measures of pricing: mark-up ratios, average charge per Medicare discharge adjusted for case mix, and average charge per Medicare visit adjusted for ambulatory payment classification relative weight. Those values are presented in the exhibit below.

The key finding: hospitals with higher percentages of revenue derived from POC provisions have significantly lower markups and lower prices. The variances are substantial and amount to a 75% to 85% difference between the highest and lowest POC quartile.

Myth #2: Fixed-fee arrangements will be easier to administer than POC contracts

Another argument to support the replacement of POC contract provisions with fixed-fee arrangements is ease of adjudication. Some may argue that in POC contracts a payer may deny specific charges. However, payers can and do deny claims or portions of claims that are paid on a fee-schedule basis.

Adjudication of claims with fixed-fee terms can be difficult for several reasons. First, anecdotal evidence indicates cases when hospitals lack the fee schedules used by payers to make payment. Either the payers have not updated and distributed new fee schedules or they do not make downloadable electronic files available to hospitals. In that scenario, the hospitals simply rely on the payer to make the appropriate payment.

Second, fixed-fee contracts often contain confusing language that makes validating payment difficult. One issue is a lack of definition for payment terms. For example, the contract may specify fee schedules for orthopedics or cardiology without expressly defining orthopedics or cardiology.

A lack of a clearly defined hierarchy in payment is another issue in many fixed-fee contracts. For example, there may be specific case rates for emergency visits and surgery, but the contract may not clearly define whether both are paid if a patient visits the ED and then has surgery, or whether only one is paid and, if so, which takes precedence. To make matters worse, such claims may be adjudicated differently over time as managed care personnel change or a person’s interpretation changes. Payers have more leverage in these matters because they are the ones holding payment.

The increased complexity in claims submission and adjudication has spawned an army of revenue cycle staff to deal with the administrative issues, which itself contributes to rising hospital costs. We examined levels of administrative and general (AG) expenses reported as a percentage of total operating expenses using HCRIS data from 2011 to 2018. In 2011, AG expenses accounted for 14.7% of total expenses. In 2018, that share had increased to 16.5%.

To put this in perspective, the average hospital in 2018 had total expenses of $268 million. If that hospital had maintained its 2011 AG expense percentage, it would have reduced expenses by $4.9 million annually. While the increase in administrative costs cannot be attributed entirely to managed care contract complexity, a portion clearly is associated with the more complex claims administration that results from fixed-fee arrangements.

Myth #3: Fixed-fee arrangements will reduce risk

Moving from a POC arrangement to a fixed-fee plan shifts the intensity of service risk from the payer to the provider. If the provider sees more patients who require higher levels of service, the provider stands to lose money. Fixed-fee plans also shift the risk of rising resource prices for items such as drugs to the provider.

Moving to payment plans where the bundled unit is even more comprehensive than an encounter, such as with episodes of care or covered lives, shifts even more risk to the hospital. Taking on more risk is viable if the assumption of risk is accompanied with the possibility of greater return, but hospitals’ experiences with larger bundled payment options have been mixed.

Some have argued that the risk shift to hospitals will give them greater incentives to become more efficient in care delivery, but the devil is in the details. How can hospitals reduce their costs if they already are relatively efficient, and will additional cost reductions affect care quality?

The delivery of specific services for an encounter of care is most likely physician-directed and subject to minimal influence by management. Managed care plans argue that POC provisions provide strong incentives to over-prescribe (e.g., do more tests) and to increase prices. Again, management does not order tests or create discharge orders; physicians do.

To some extent managed care payers are protected from large rate increases by rate limit clauses in POC contracts. Most often rate increases above a certain level, such as 5%, are neutralized. These provisions shift the risk of increases in resource prices to the hospital.

Why rate limit clauses are a possible solution

Rate limit clauses — specifically indexed rate limit provisions — offer a potential solution to spiraling hospital prices. Indexed rate limits exist in a limited number of plans across the country and are easy to understand and administer.

Most rate limit clauses are on a “use it or lose it” basis. In an indexed arrangement, however, if the allowed rate of increase is not used, the POC payment percentage increases.

As an illustration, assume that a contract pays 50% of billed charges and has a 4% rate increase limit. If the hospital chooses not to increase prices in a given year, the POC payment percentage would increase to 52%. This mechanism would maintain payment at the predetermined rate of increase for both provider and payer.

Instead of raising prices or freezing them, assume that the hospital rolls prices back by 20%. The new payment rate would be 65% [(1.04/0.80) X 50%]. A service currently priced at $100 would be reduced to $80 but still be paid $52 ($80 x 0.65), just as if the provider raised the price by 4%, to $104.

The key is getting all payers to agree to the inclusion of indexed rate limits. Without acceptance by all payers with negotiated contracts, those choosing not to adopt an indexed arrangement would have lower payments relative to other payers. Fixed-fee provisions may also need adjustment to remove “lesser than” provisions if prices are in fact reduced.