Telehealth became a necessity during the COVID-19 pandemic, and experts say it’s here to stay

Experts weigh in on the future of telehealth

Vismai Sinha, MD, knows how to spot an opportunity in times of adversity. So when the COVID-19 pandemic hit and she began working at home, the physician at OhioHealth Physician Group in Columbus and her husband Rajeev decided it was time to get a pet. After watching a comprehensive PowerPoint presentation by their daughter about guinea pig and hamster care, they decided for the work involved, they might as well get a dog.

These days, Sinha works two days a week at home, visiting with patients via computer in her home office and making sure Belle, the family’s French bulldog, gets outside while Sinha checks on her daughters, 10 and 8, who are attending school virtually for the fall semester.

Like many parents, Sinha has had to adjust to remote work during the pandemic, but as a physician, she’s had to change the way she does her job from start to finish. Like many physicians, she saw her work shift from in-person visits to telehealth, later settling into a hybrid model. The transition was exciting, but not easy.

“I was excited about [telehealth], but I was definitely nervous,” she said. “I grew up with paper charting. In my training, you always had hands on a patient. [But] there’s so much more I can do through telehealth than I initially thought I could.”

She soon discovered opportunities she hadn’t anticipated. For one thing, more time with the patient. For in-office visits, which Sinha currently conducts three work days each week, social distancing protocols dictate that patients call when they arrive in the parking lot to get checked in and then complete a screening inside the building’s lobby before coming up to the office.

“It adds so much more time,” she said. On most days, Sinha finds she runs 20 to 30 minutes behind because of the new protocols. Telehealth visits eliminate the drive for both patients and Sinha, and the administrative work is taken care of far ahead of the scheduled appointment.

“[With telehealth visits], I have 20 minutes that I am dedicated to talking to that patient,” she said. “We really form quite a connection.”

Telehealth has been around for years, but during the COVID-19 pandemic, it has picked up steam and become a larger part of healthcare culture. The new telehealth norm is partially due to the need for many hospitals to cancel nonemergent procedures to free up space to accommodate surges of patients with COVID-19 and the inability of physician offices to take patients as usual when social distancing practices began. Also, CMS enacted temporary policy changes allowing providers to expand their telehealth offerings.

Now that CMS has proposed a permanent expansion of some of those permissions, physicians, revenue cycle personnel and leaders are looking to shift their mindset from seeing telehealth as a temporary solution to considering it a fixture in the healthcare landscape.a

The challenge of the quick pivot

Telehealth did not have a strong presence at OhioHealth prior to the pandemic, but a team was working to map out a long-term strategy to offer telehealth, according to Nicole Walker, OhioHealth’s director of revenue cycle. When the pandemic hit and people began to move to telehealth visits, OhioHealth leaders created a large, multi-departmental team to make decisions around telehealth and other issues. For 14 weeks, team members including Walker met virtually every day for several hours to work through those issues. A smaller version of that team continues to meet regularly.

“It took a large team to say, what do we as an organization want to offer, what can we offer safely for ourselves and our patients and what is our standard work around that?” Walker said. Some examples of those issues were:

- Issues that are clinically appropriate to address over the phone versus in person

- Prescribing protocols, particularly around controlled substances

- Lack of laptops for providers, who had to use their own personal devices for a time, which introduced risk

- Clinical workflows and privacy issues in pediatrics, particularly when photos are shared

For Walker, pivoting to a telehealth-heavy strategy was not only an administrative challenge, but also a moral one. People who work in revenue cycle typically rely heavily on data, but in a situation where data simply wasn’t available, she had to get comfortable making recommendations and decisions based on estimates and expert opinion. The process also was stressful because she knew the stakes were high, she said.

“As a non-clinical leader, I’ve never had the feeling that I hold someone’s life in my hand,” she said. “I felt like I was working against a deadline that I didn’t really know for sure. And if I don’t pull my weight and do my job to the best of my ability, people could die.”

During that crucial time, team members leaned on each other’s expertise and worked methodically to put workflows in place that could be easily adjusted going forward. (See the sidebar at the bottom of this article, “OhioHealth overcomes revenue cycle challenges posed by telehealth visits.”)

For Sinha, the adjustments were more practical. Some patients had trouble with the technology. And patient privacy is now a family consideration, as she must restrict her children’s access to their play area because it’s near her work area.

“They’re really understanding. They know when Mommy is with patients, she needs to be left alone,” she said. “They know when that sign is up on the door, they cannot come downstairs and disturb me.”

The opportunity of flexibility

At Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the process of moving quickly toward a telehealth strategy included education for providers, according to Alex Carter, a physician’s assistant and innovation telehealth clinical advisor at the health system.

Some providers were hesitant because they weren’t sure how to translate in-person care to virtual and provide the same level of quality. Presbyterian ran a focus group and held an informational session about how telehealth could work well while the provider worked from home, and early adopters were given the opportunity to share their tips and feedback.

“It’s not a one-size-fits-all experience,” she said. “There are some constants … but we also know that providers have their own style and their own personality.”

Physicians who have adapted to new clinical workflows tend to like the way their days are structured, and many find career flexibility they didn’t have before, Carter said. For example, telehealth at Presbyterian’s urgent care clinics is exclusively asynchronous (that is, care where a patient uploads information and a physician logs on later and responds), which allows physicians to work where they like and, to some degree, when they like. Some physicians do telehealth work in the office between live visits, and some work the entire day from home, focusing only on remote patients.

“There’s a lot of flexibility, and it’s very customizable,” Carter said. It’s also efficient: Presbyterian’s response time is typically less than 10 minutes.

According to Oliver Lignell, vice president of virtual health at AVIA, flexibility and workflows should also take the patient’s convenience into account. For example, there should be a mechanism that allows a physician to convert an asynchronous visit to a synchronous one.

“You need all those modalities,” he said. “You need to be able to move between them and choose what’s appropriate clinically.”

The future of telehealth

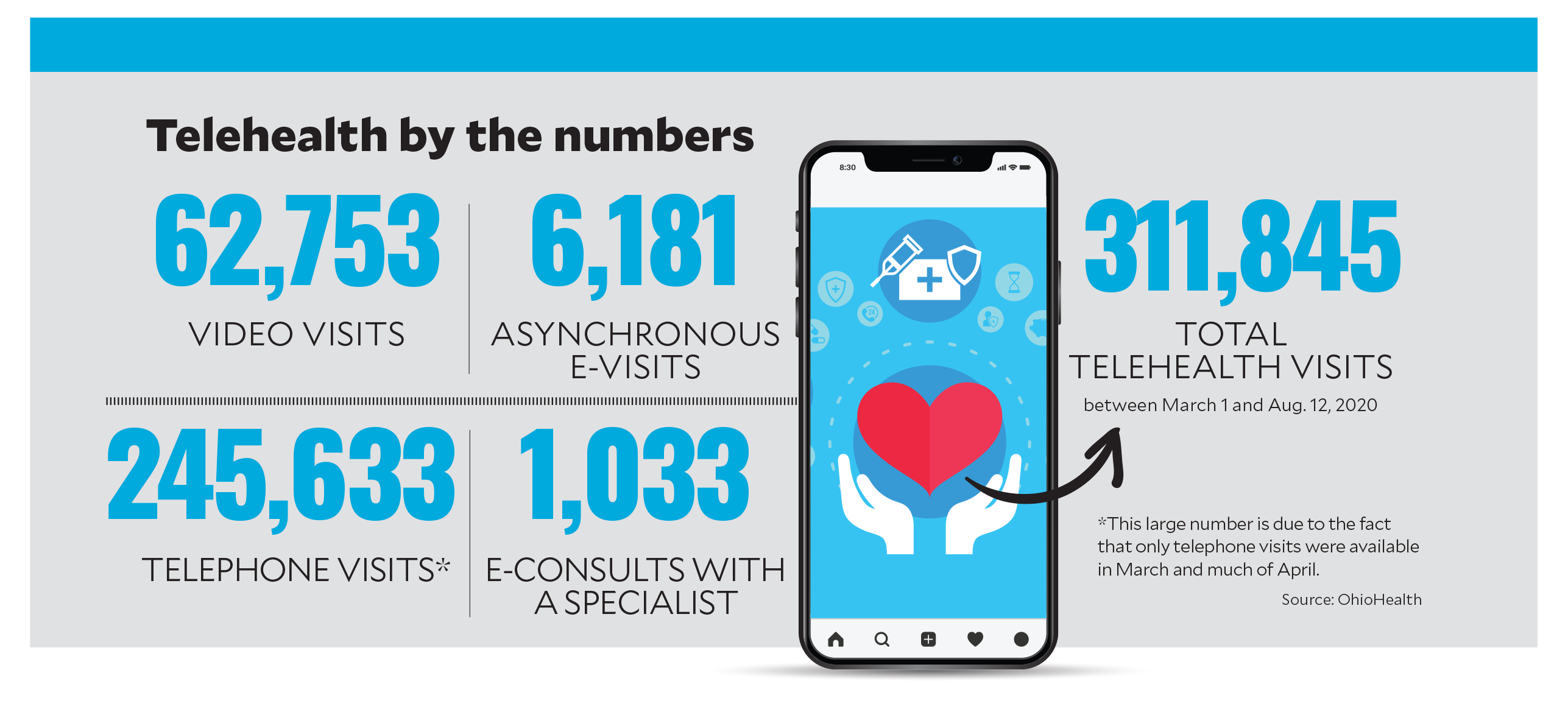

Early on, most of Sinha’s remote visits were conducted over the phone (see the sidebar “Telehealth by the numbers” below). But as telehealth becomes a more important component of care, the technology is improving, and on the practical side, CMS’s plan to expand telehealth permanently does not currently include long-term plans for telephone visits to be widely used.

Video visits, however, allow a physician to see how a patient lives and assess social determinants of health in ways an office visit can’t, Sinha said. For example, she can ask to see prescription bottles or the food in the patient’s refrigerator. She can see if a patient has family helping and advise them on proper techniques to perform routine health checks. All this information can be helpful in the course of treatment, particularly for chronic conditions.

Telehealth presents huge opportunities for chronic disease management, according to Lignell. Asynchronous visits can be more convenient for the patient and the provider, he said.

Asynchronous telehealth tools also can be useful for provider-directed care, Lignell said. Physicians can monitor patients remotely and request an appointment if their condition appears to worsen.

Uses like this are already being seen as opportunities by companies like Teladoc. The company, which previously operated in the acute care space, recently made an $18.5 billion deal to acquire Livongo, a digital health management company that focused on chronic conditions.b

Telehealth also presents opportunities to provide more care, and better care, in rural areas, according to Doug Morse, CEO of Hansen Family Hospital in Iowa Falls, Iowa.

“We’re looking at telehealth as a means to put clinical talent and data at the right place and the right time,” he said.

Rural hospitals often have difficulty recruiting physicians, but through telehealth, healthcare organizations can attract top talent and provide care at a lower cost, Morse said. In addition, physicians corresponding with each other via telehealth tools can help patients get the care they need at everyone’s convenience. Many patients in rural communities are forced to travel several hours for routine specialist appointments, but telehealth, along with tools that allow information sharing between providers, can make for a better patient and provider experience.

“The exciting part of this is, it brings the patient into their own care,” Morse said. “It really seems like if we, and as we, arrange these resources and organize around the patient condition across multiple sites, we can bring more services to a rural community, not less.”

Sidebar: Telehealth by the numbers

Sidebar: OhioHealth overcomes revenue cycle challenges posed by telehealth visits

Revenue cycle workflows can become particularly difficult with telehealth. According to Nicole Walker, OhioHealth’s director of revenue cycle, many payers took their time creating policies around telehealth, even after the initial push in March to provide care remotely. When that guidance did begin to come in, payer policies were inconsistent, making it difficult for revenue cycle personnel to automate the process the way the way it’s typically done.

At OhioHealth, most office visits are sent to payers automatically, without a review by coding staff, Walker explained. Telehealth guidance varied by payer, so every telehealth claim had to be looked over carefully by a coder.

In addition, many payers initially weren’t ready to accept telehealth claims.

“We were able to create a workflow where we could hold those charges until the payers were ready to accept them,” Walker said.

The next challenge was that many payers changed their guidance, some more than once.

“We had to go back numerous times and re-code services before we could send them out the door,” she said. This process of rework applied to about 70,000 claims, and even after that, many were denied. The amount of work for coders was offset for a while by the lack of work on the elective procedure side, but now that those have ramped up and payer policies continue to change, OhioHealth finds it a challenge to keep up, Walker said. The team is now working proactively to reach out to payers to ensure they have the most current information and to keep an eye on policies that are set to expire in the coming months.

Footnotes

a. CMS, “Trump administration proposes to expand telehealth benefits permanently for Medicare beneficiaries beyond the COVID-19 public health emergency and advances access to care in rural areas,” Aug. 3, 2020.

b. Landi, H., “Telehealth leader Teladoc to buy Livongo in $18.5B deal,” Fierce Healthcare blog, Aug 5, 2020.